Dr Hiroko Oe writes for The Conversation about Japan’s Edo period and how it led to the development of sustainable lifestyle practices…

How centuries of self-isolation turned Japan into one of the most sustainable societies on Earth

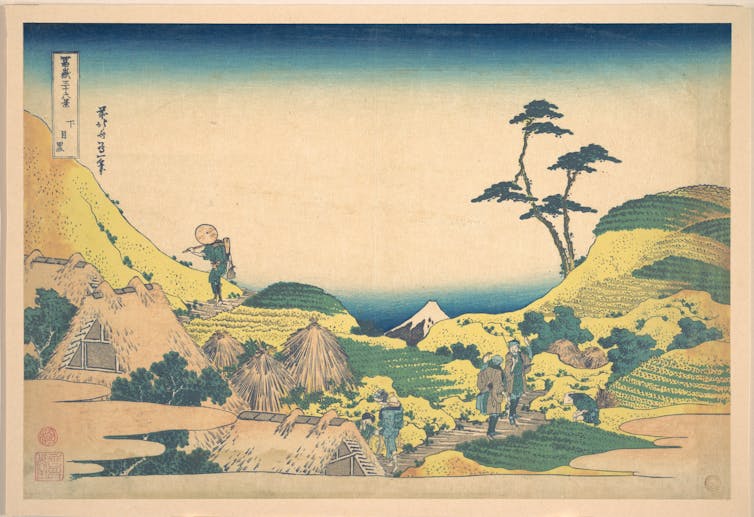

The Met Museum

Hiroko Oe, Bournemouth University

At the start of the 1600s, Japan’s rulers feared that Christianity – which had recently been introduced to the southern parts of the country by European missionaries – would spread. In response, they effectively sealed the islands off from the outside world in 1603, with Japanese people not allowed to leave and very few foreigners allowed in. This became known as Japan’s Edo period, and the borders remained closed for almost three centuries until 1868.

This allowed the country’s unique culture, customs and ways of life to flourish in isolation, much of which was recorded in art forms that remain alive today such as haiku poetry or kabuki theatre. It also meant that Japanese people, living under a system of heavy trade restrictions, had to rely totally on the materials already present within the country which created a thriving economy of reuse and recycling). In fact, Japan was self-sufficient in resources, energy and food and sustained a population of up to 30 million, all without the use of fossil fuels or chemical fertilisers.

The people of the Edo period lived according to what is now known as the “slow life”, a sustainable set of lifestyle practices based around wasting as little as possible. Even light didn’t go to waste – daily activities started at sunrise and ended at sunset.

Clothes were mended and reused many times until they ended up as tattered rags. Human ashes and excrement were reused as fertiliser, leading to a thriving business for traders who went door to door collecting these precious substances to sell on to farmers. We could call this an early circular economy.

katsushikahokusai.org

Another characteristic of the slow life was its use of seasonal time, meaning that ways of measuring time shifted along with the seasons. In pre-modern China and Japan, the 12 zodiac signs (known in Japanese as juni-shiki) were used to divide the day into 12 sections of about two hours each. The length of these sections varied depending on changing sunrise and sunset times.

During the Edo period, a similar system was used to divide the time between sunrise and sunset into six parts. As a result, an “hour” differed hugely depending on whether it was measured during summer, winter, night or day. The idea of regulating life by unchanging time units like minutes and seconds simply didn’t exist.

Instead, Edo people – who wouldn’t have owned clocks – judged time by the sound of bells installed in castles and temples. Allowing the natural world to dictate life in this way gave rise to a sensitivity to the seasons and their abundant natural riches, helping to develop an environmentally friendly set of cultural values.

Working with nature

From the mid-Edo period onwards, rural industries – including cotton cloth and oil production, silkworm farming, paper-making and sake and miso paste production – began to flourish. People held seasonal festivals with a rich and diverse range of local foods, wishing for fertility during cherry blossom season and commemorating the harvests of the autumn.

This unique, eco-friendly social system came about partly due to necessity, but also due to the profound cultural experience of living in close harmony with nature. This needs to be recaptured in the modern age in order to achieve a more sustainable culture – and there are some modern-day activities that can help.

For instance zazen, or “sitting meditation”, is a practice from Buddhism that can help people carve out a space of peace and quiet to experience the sensations of nature. These days, a number of urban temples offer zazen sessions.

Palatinate Stock / shutterstock

The second example is “forest bathing”, a term coined by the director general of Japan’s forestry agency in 1982. There are many different styles of forest bathing, but the most popular form involves spending screen-free time immersed in the peace of a forest environment. Activities like these can help develop an appreciation for the rhythms of nature that can in turn lead us towards a more sustainable lifestyle – one which residents of Edo Japan might appreciate.

In an age when the need for more sustainable lifestyles has become a global issue, we should respect the wisdom of the Edo people who lived with time as it changed with the seasons, who cherished materials and used the wisdom of reuse as a matter of course, and who realised a recycling-oriented lifestyle for many years. Learning from their way of life could provide us with effective guidelines for the future.![]()

Hiroko Oe, Principal Academic, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm

3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March

Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward?

Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward? BU academics in the news in Nepal

BU academics in the news in Nepal ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease