Babis Fassoulas, Author provided

There has been a lot of interest in our discovery of nearly-6m-year-old footprints on Crete, first reported by the The Conversation – suggesting that human ancestors could have roamed Europe at the same time as they were evolving in East Africa.

Sadly the site was vandalised in the last week, with four or five of the 29 tracks stolen. We are fortunate that many of the best tracks remain – the people who did it clearly didn’t know what they were looking for. Our guess is that they were simply intending to sell them.

The theft occurred despite the site being afforded protection under Greek heritage law and being in the care of local officials. Police, we are told, have made an arrest in connection with the incident, and it is hoped that the missing material will be returned soon. The damage, however, is irreparable.

Babis Fassoulas, Author provided

The Cretan authorities moved swiftly to bury the site temporarily while a more permanent conservation solution, such as moving the entire surface, is sought. We are lucky that the whole area has been 3D-scanned with an optical laser scanner in high resolution as part of the original study. In due course this data will be made available via the Natural History Museum of Crete and the Museum of Evolution at Uppsala University in Sweden. So there will fortunately not be much of an impact on the research.

Yet the event is devastating. To understand the significance to someone who studies ancient tracks like these, consider it equivalent to an attempt to steal part of the Sphinx at Giza or vandals dislodging one of lintel blocks at Stonehenge.

Unfortunately, the theft and vandalism of tracks is nothing new. For example, there was a recent case on the Isle of Skye in Scotland of vandalised dinosaur tracks dating from around 165m year ago that lead to a police probe. The ethics around the collection and sale of fossils and artefacts is complex, and many of the great scientific collections today are based on collection and sales by amateurs in the past. Ultimately, it seems wrong to collect and sell artefacts that there’s only a limited number of.

Conversation challenges

But how can you conserve what is essentially a slab of soft rock, close to the sea and open to the elements? Oddly, erosion at such sites is to be encouraged because it often helps reveal new surfaces which may contain additional prints.

It’s tricky – a problem I first faced following my discovery of the Ileret hominin footprints, the second oldest such tracks in the world at the time, and preserved in nothing but packed silt.

Babis Fassoulas, Author provided

I did some research on this with colleagues and concluded that the only option is to excavate and digitally record them in 3D. This can be done either with a laser scanner or just with a digital camera in the field. Some 20 pictures of a track from different angles is enough to create a 3D image. These days 3D printers can easily create models for museums and for collectors.

Digital preservation is probably the key for the Cretan tracks as well. This worked well for the 2,100-year-old human footprints of Acahualinca

in Managua (Nicaragua), where the originals are perfectly preserved under a roof built over the site, and in an adjacent museum.

The 120,000-year-old human footprints at Nahoon Point in South Africa are marked by a footprint-shaped visitors’ centre that looks great from Google Earth. There are also a number of excellent examples of dinosaur track sites preserved in museums and under shelters, such as those at Las Cerradicas in Spain.

Perhaps the most controversial of conservation solutions has been to bury the world’s oldest confirmed hominin footprints – from Laetoli in Tanzania – which were first documented in the late 1970s. These tracks were buried as a way of protecting them from weathering and natural-decay.

There has been extensive debate about what should happen at this site and many scientists are unhappy about the lack of access. Plans for the site over the years have varied from an on-site museum to the removal of the whole slab to another site. The debate continues, but ultimately it is money that precludes a solution that would allow access to the public and scientists alike.

Author provided

Indeed, the challenge is always money. It is expensive to erect and maintain protective structures, and to gain funds you need publicity to ensure that all the stakeholders involved are aware of the scientific, social and emotional value of a site.

One of the reasons for publicising the Trachilos tracks was not only to get the discovery debated in open scientific circles, but also to raise its public profile – thereby seeking better protection and ultimately its preservation in a local museum. That would bring visitors and fuel local revenue.

![]() The trouble is the very publicity aimed to assist the site’s protection may have led to an enhanced perception of its monetary value. After all, the site had been known locally for years. Publicity though, is a double-edged sword and we have been lucky on this occasion to avoid the full length of its blade.

The trouble is the very publicity aimed to assist the site’s protection may have led to an enhanced perception of its monetary value. After all, the site had been known locally for years. Publicity though, is a double-edged sword and we have been lucky on this occasion to avoid the full length of its blade.

Matthew Robert Bennett, Professor of Environmental and Geographical Sciences, Bournemouth University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Conversation article – Fossil footprints: the fascinating story behind the longest known prehistoric journey

Conversation article – Fossil footprints: the fascinating story behind the longest known prehistoric journey What ancient footprints can tell us about what it was like to be a child in prehistoric times

What ancient footprints can tell us about what it was like to be a child in prehistoric times How to hunt a giant sloth – according to ancient human footprints

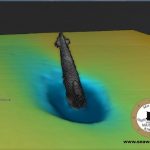

How to hunt a giant sloth – according to ancient human footprints Sunken Nazi U-boat discovered: why archaeologists like me should leave it on the seabed

Sunken Nazi U-boat discovered: why archaeologists like me should leave it on the seabed

Nursing Research REF Impact in Nepal

Nursing Research REF Impact in Nepal Fourth INRC Symposium: From Clinical Applications to Neuro-Inspired Computation

Fourth INRC Symposium: From Clinical Applications to Neuro-Inspired Computation ESRC Festival of Social Science 2025 – Reflecting back and looking ahead to 2026

ESRC Festival of Social Science 2025 – Reflecting back and looking ahead to 2026 3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Cookies – Tuesday 13 January 10-11am

3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Cookies – Tuesday 13 January 10-11am Dr. Chloe Casey on Sky News

Dr. Chloe Casey on Sky News ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published

Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease