In academic life rejection is the norm, for both journal articles and grant applications, the average academic is more likely to fail than to succeed at any time. This can also be true, although to a lesser extent, for applications to present at academic conferences. At the time of writing this blog (12 February 2022), I have 299 published papers listed on the databases SCOPUS. Of these nearly 300 papers only two papers ever were accepted on first submission as submitted. Most papers went through one or two rounds revision in the light of comments and critique offered by reviewers, and sometimes also additional feedback from the journal’s editor.

In academic life rejection is the norm, for both journal articles and grant applications, the average academic is more likely to fail than to succeed at any time. This can also be true, although to a lesser extent, for applications to present at academic conferences. At the time of writing this blog (12 February 2022), I have 299 published papers listed on the databases SCOPUS. Of these nearly 300 papers only two papers ever were accepted on first submission as submitted. Most papers went through one or two rounds revision in the light of comments and critique offered by reviewers, and sometimes also additional feedback from the journal’s editor.

After rejection by the first journal, your paper needs to be rewritten before submitting it to another journal. Obviously, this process of rewriting and resubmitting takes time as different journals have different styles, lay-outs, sub-headings, audiences, and often peculiar ways of referencing. I would guess more than half of my papers have been through the review process of at least two journals. Quite a few of my published papers were accepted by the third or even fourth journal to which we had submitted them. Persistence is the name of the game. Some paper fell by the wayside often after second submission, if especially if review process had been time-consuming and the reviewers very critical and demanding too many changes.

Peer review can be very good and constructive but also brutal and destructive. Blind peer-review is a fair process as it means the quality of the paper is all that counts in getting accepted. I have had the pleasure of being co-author on papers rejected by journals for which I was: the book review editor at the time (Sociological Research Online), on the journal’s editorial board at the time of submission (e.g. Midwifery, Nepal Journal of Epidemiology), one of journal’s Associate Editors (BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth) and, to top it all, on which I was one of the two editors (Asian Journal of Midwives).

Grant applications in the UK have a one in eight to one in ten chance of success. Most of our successful grant applications have been resubmissions, with attempts to improve the application each time in the light of reviewers’ comments. For example, our successful application to THET (Tropical Health & Education Trust) resulted in the funded project ‘Mental Health Training for Rural Community-based Maternity Care Workers in Nepal‘ [1], led by Bournemouth University (see picture). This THET project was organised by Tribhuvan University in collaboration with Bournemouth University and Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU). However, I was only successful during our second submission. Our first submission was rejected the year before with feedback that our partner organisation in Nepal was deemed to be too small. In the resubmission we changed to work with colleagues at Tribhuvan University, the oldest and largest university in Nepal. Apart from some further, but minor changes, this was really the main change between the rejected and the successful application.

The situation for conferences is slightly better, the success rate for an application to present a paper or poster are higher. This is partly because conference organisers realise that most academics are unlikely to get funding from their institution unless they present something. Conferences are often themed and submitted abstracts are peer-reviewed. This makes in important to write a clear abstract, focusing in on the conference theme.[1] In the past I have had the honour of being rejected to present a paper at a BSA Medical Sociology Conference, whist I was on the organising committee.

Prof. Edwin van Teijlingen

CMMPH

References

- Simkhada, P., van Teijlingen E., Hundley, V., Simkhada, BD. (2013) Writing an Abstract for a Scientific Conference, Kathmandu University Medical Journal 11(3): 262-65. http://www.kumj.com.np/issue/43/262-265.pdf

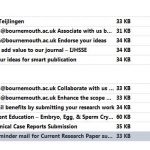

Two papers rejected the day after submission in same week

Two papers rejected the day after submission in same week Academia is becoming more demanding

Academia is becoming more demanding Three-and-a-half years to get published

Three-and-a-half years to get published

Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop

Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching

UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives BRIAN upgrade and new look

BRIAN upgrade and new look Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh

Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease