Dr Melanie Klinkner shares her experience of undertaking research in Cambodia…

Dr Melanie Klinkner shares her experience of undertaking research in Cambodia…

Perhaps it is due to a genetic predisposition to embrace the continental Kaffeehaus tradition of discussing matters for hours on end or simply because of an affinity to the Socratic dialogue, interviewing has been a key component of my research. It would be wrong to say that I am not nervous before each interview or don’t question my methodological approach, but, in general, interviews have been exciting, worthwhile and a superb way to network. I keep being amazed by the generosity of participants in giving up their time, going to the trouble of meeting me, sharing their experience and expertise, sending relevant information or answering follow-up questions.

The experiences from a fieldtrip to Cambodia epitomises the fun of qualitative research for me. On arrival at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia outside the capital Phnom Penh, I was met by the then head of PR who had not only organised an interview schedule with judges, prosecutors and defence lawyers but also offered me a tour of the (then not quite complete) building. Sure, this might have been part of their general public relations efforts, but it was me who benefitted from meeting these individuals. I was the lucky one sitting in the office of a Cambodian participant, with a translator present, conducting an interview whilst feeling strangely observed by the statue of an elusively smiling Khmer head on the top of a cupboard. I was similarly impressed with one interviewee who was on a business trip to Bangkok whilst I visited Phnom Penh, but was still happy to meet me in a Hotel lobby in the centre of Bangkok an hour after my plane from Phnom Penh touched down on Suvanarbhumi Airport. It would also be amiss to forget the other impressions gathered on this trip. The taxi driver who took me to the Extraordinary Chambers each day and dropped me at the Killing fields on the outskirts of Phnom Penh shared his experiences from the Khmer Rouge area. A young TukTuk driver and English language teacher practiced his English by telling me about the education system. Whilst not explicitly relevant to the research – implicitly this information is priceless.

The experiences from a fieldtrip to Cambodia epitomises the fun of qualitative research for me. On arrival at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia outside the capital Phnom Penh, I was met by the then head of PR who had not only organised an interview schedule with judges, prosecutors and defence lawyers but also offered me a tour of the (then not quite complete) building. Sure, this might have been part of their general public relations efforts, but it was me who benefitted from meeting these individuals. I was the lucky one sitting in the office of a Cambodian participant, with a translator present, conducting an interview whilst feeling strangely observed by the statue of an elusively smiling Khmer head on the top of a cupboard. I was similarly impressed with one interviewee who was on a business trip to Bangkok whilst I visited Phnom Penh, but was still happy to meet me in a Hotel lobby in the centre of Bangkok an hour after my plane from Phnom Penh touched down on Suvanarbhumi Airport. It would also be amiss to forget the other impressions gathered on this trip. The taxi driver who took me to the Extraordinary Chambers each day and dropped me at the Killing fields on the outskirts of Phnom Penh shared his experiences from the Khmer Rouge area. A young TukTuk driver and English language teacher practiced his English by telling me about the education system. Whilst not explicitly relevant to the research – implicitly this information is priceless.

It is with some sadness that I read of the difficulties the Extraordinary Chambers are facing with allegations of corruption, lack of funding, political meddling, the age and death of defendants hampering its progress. Surely Cambodia and the Cambodian people deserve better. Perhaps one day (when the children are older) I will be able to return to Cambodia for an interdisciplinary study to further our understanding as to the forensic, legal but also cultural significance the displayed human remains have within Cambodian Society – they are a fascinating substrate for research. For now, I have one small regret: I should have bought a sculpture of a Khmer head with its elusive smile to put on my book shelve at home.

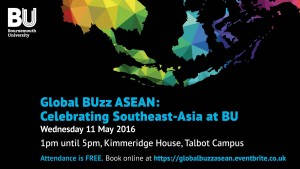

BU invites you to celebrate the countries that make up the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) region, as we host an event that showcases the variety of cultures and BU’s relationships across Southeast Asia on Wednesday 11 May.

BU invites you to celebrate the countries that make up the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) region, as we host an event that showcases the variety of cultures and BU’s relationships across Southeast Asia on Wednesday 11 May.

BU academics in the news in Nepal

BU academics in the news in Nepal New CMWH paper on maternity care

New CMWH paper on maternity care From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives: Reflections from the SPROUT Network Event

From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives: Reflections from the SPROUT Network Event ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease