The latest NCCR seminar took place on 15 January when we welcomed the Head of the Comparative Politics and Media Centre, Professor Darren Lilleker.

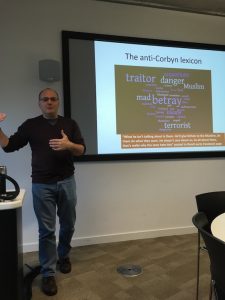

Professor Lilleker’s talk drew on analysis of the lexis used on social media to argue that an embedded underlying myth of Britishness informed much of the debate around the EU Referendum. The Leave EU lexicon was characterised by terms such as ‘free’ and ‘rule’, with words such as ‘traitor’ and ‘betray’ attached to Jeremy Corbyn by the Brexit Party. Links with traditional British anthems such as ‘Land of Hope and Glory’, and ‘Rule Britannia’ were explored (alongside reference to ‘Jerusalem’) and analysed against a model of British particularism (Dowling) which privileges qualities such as strength, superiority, benevolence, and exceptionality. The way that this set of qualities is reinforced through British secondary school curriculum (textbooks such as Crowther, The History of Britain) was discussed, noting that the GCSE history curriculum is fragmented and one-sided, with key moments in British history being explored devoid of context, and framed to sustain a view of empire (such as Henry VIII who ‘freed us from the Church of Rome’, Elizabeth I who ruled the waves, or the Pilgrim Fathers who established the USA). Without linkage or linearity, British schooling thus provides a selective view of its history. Similarly, the adoption of an ‘Anglo Saxon’ origin excludes all the other nationalities that form the British ancestry, and allows for clear linkages to be made with Germany (relevant to the British Royal family) as well as oppositions with countries such as France. These elements sustain the presence of myths of empire, particularism, and power.

The session was very well-attended and produced some thoughtful discussion, which explored various definitions of myth (Barthes, Levi-Strauss) and its role as a mediating narrative or therapeutic alternative to history, debated why people might feel compelled to identify with these (dignity, history), noted the essential nature of a mythic past to fascist ideology (Stanham), and the consistent recirculation of such myths (e.g. in war films), the relevance of the manner in which an empire ends and the subject status of British citizens, the role of the literary market in selling textbooks that must appeal to the buyer, and reflected on the etymology of ‘Great’ Britain, which in other languages also carries traces of particularism, such as Chinese where it is directly translated as ‘brave’.

Building Roman Britain: The Movie

Building Roman Britain: The Movie

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives BRIAN upgrade and new look

BRIAN upgrade and new look Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh

Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh Exploring Embodied Research: Body Map Storytelling Workshop & Research Seminar

Exploring Embodied Research: Body Map Storytelling Workshop & Research Seminar Marking a Milestone: The Swash Channel Wreck Book Launch

Marking a Milestone: The Swash Channel Wreck Book Launch ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease