How we experience the environment around us involves the brain combining information from our different sensory systems. For example, signals from our inner ears and joints tell us how we are positioned compared to gravity. The brain then combines this with what we see around us to help us maintain an upright position (i.e. prevent us falling over). Our perception of upright changes throughout our lifetime and different medical conditions can affect this which may make you reconsider whether your picture frames are straight.

For our first Café Scientifique of 2020, Dr Sharon Docherty switched roles from Cafe Sci’s regular host to this month’s speaker. Outlining some of the research she has conducted in the area of perception of visual vertical, Sharon presented findings from a range of studies to illustrate how our perception changes from childhood through to older age as well as how conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, diabetes and neck pain can affect this.

How is perception of vertical measured?

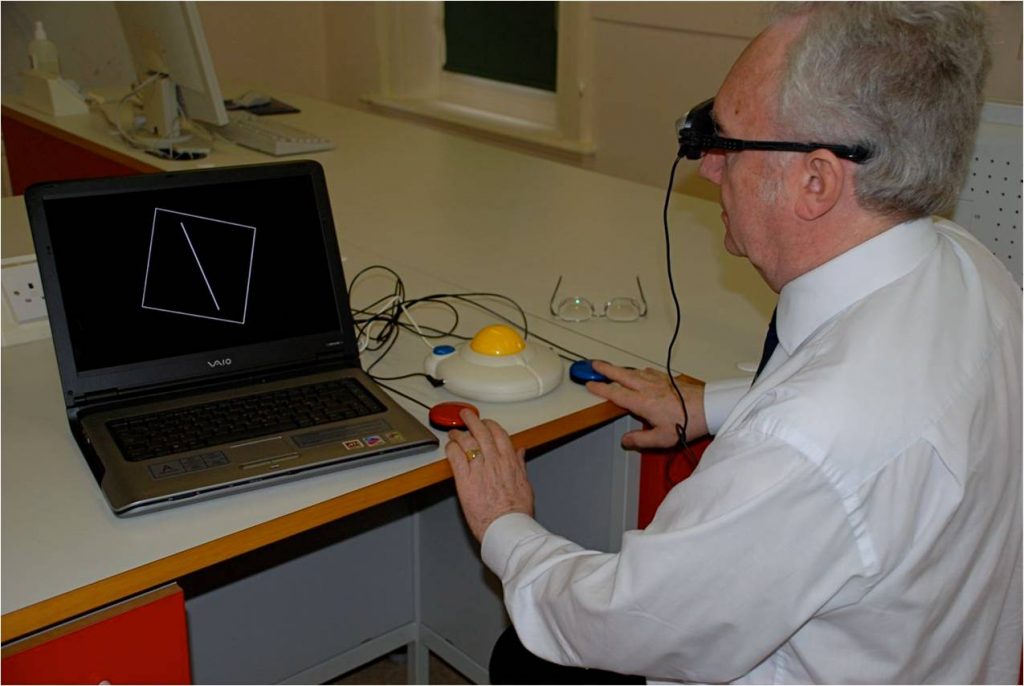

Sharon has spent years developing a computerised test along with her colleague, Jeff Bagust. The test involves moving a line from an angle of 20 degrees into a position you think is vertical. In some presentations within the test, only the line is on the screen, testing your ability to make the judgement without any visual cues from your environment. In others, there is a square frame surrounding the line providing visual cues for both vertical and horizontal. This is known as the Rod and Frame Test. As well as presenting the frame in an upright position, in some of the tasks the frame is tilted by 18 degrees. Tilting the frame provides a confusing visual signal to your brain that affects people’s perception in different ways. It is a measure of how well your brain can adapt to relying on the other sources of information (inner ears, muscles and joints). All of this is conducted viewing the test through video glasses eliminating clues from the external environment. This means the test can be carried out almost anywhere.

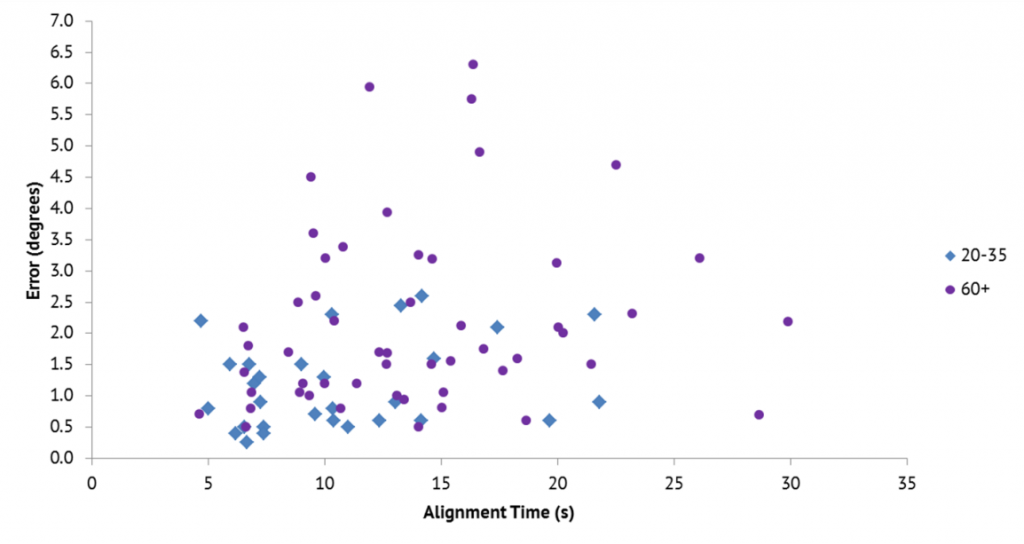

As well as measuring the effect of tilting the frame in terms of degrees of error from true vertical, the system also records the amount of time it takes the participant to make the adjustment. Again, the difference between when the frame is tilted and when it isn’t can be quite remarkable for some people. It doesn’t necessarily mean those who take longer are more accurate in either younger or older adults (see graph). Another important aspect that is measured is the consistency with which people are able to judge the vertical position. A review of studies of different clinical conditions that Sharon and Jeff have conducted show that those participants with possible neurological complications had higher individual variability of error than healthy controls.

What does this mean?

What does this mean?

The occurrence of above normal errors and high individual variability in those people with possible neurological complications suggests that the test may be a useful screening tool in other conditions such as falls in older adults.

Where to from here?

“We have recently completed a study comparing a group of 20-35 year old’s with a group 60 years and older. The results showed an increase of 2 degrees or more error in the older group. We plan on looking at how the results of the rod and frame test compare with the purely visual task of detecting contrast between an object and its background. This should help us better understand the part deterioration of the visual system plays in perception of vertical.”

“Another phenomenon we have observed is that some people do not seem to understand the task as soon as the frame is tilted, even after a practice run when they have completed it correctly. Instead of aligning to vertical, they carefully move the line to match the angle of the frame. We are able to distinguish these people from those that have genuinely high errors as they consistently position the line within a few degrees of the frame angle. The plan is to combine this with tests of cognitive function to try to explain what is happening.”

Dr Sharon Docherty reflects on her experience of speaking at Café Scientifique: “Following the talk we had a really interesting discussion around the subject. It certainly left me with lots to think about and quite a few new research ideas. It’s not just the audience who have a great time, presenters have left smiling and commenting on how much they enjoyed the experience… often with a few new research ideas courtesy of the audience!”

Dr Sharon Docherty reflects on her experience of speaking at Café Scientifique: “Following the talk we had a really interesting discussion around the subject. It certainly left me with lots to think about and quite a few new research ideas. It’s not just the audience who have a great time, presenters have left smiling and commenting on how much they enjoyed the experience… often with a few new research ideas courtesy of the audience!”

Audience members share their comments; “It is a really interesting topic and great location.” “Marvellous & stimulating.”

The next Café Scientifique will take place at Café Boscanova on Tuesday 3 March from 7:30-9pm (doors open at 6:30pm)

We’ll be joined by Ediz Akcay who will be discussing;

‘The Dark Side of Personalisation: AI, Voice Recognition and Beyond’

“I’m afraid I can’t do that…” – a famous line from 2001: A Space Odyssey, in which the AI software HAL rebels to take control of the spaceship. We are now far beyond the year 2001 and we already have our own AI-supported voice recognition devices in our pockets, houses, and cars, used by adults and children alike. Luckily, they do not rebel against our commands – yet. These devices bring advantages in convenience and accessibility, playing a song has never been easier, but at what cost? Join us to discuss the ethics of the many new ways that companies listen to, track and store information about us using voice recognition and AI.

There’s no need to register, make sure you get there early though as seats fill up fast!

If you have any questions please do get in touch

Find out more about Café Scientifique and sign up to our newsletter to hear about our exciting programme of research events for the public; www.bournemouth.ac.uk/cafe-sci

Cafe Scientifique Tuesday 4 February: Crooked picture frames and ageing of perception

Cafe Scientifique Tuesday 4 February: Crooked picture frames and ageing of perception

REF Code of Practice consultation is open!

REF Code of Practice consultation is open! BU Leads AI-Driven Work Package in EU Horizon SUSHEAS Project

BU Leads AI-Driven Work Package in EU Horizon SUSHEAS Project Evidence Synthesis Centre open at Kathmandu University

Evidence Synthesis Centre open at Kathmandu University Expand Your Impact: Collaboration and Networking Workshops for Researchers

Expand Your Impact: Collaboration and Networking Workshops for Researchers ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease