Professor Dinusha Mendis writes for The Conversation about the potential copyright implications of AI as a lawsuit is lodged by the New York Times against the creator of ChatGPT…

How a New York Times copyright lawsuit against OpenAI could potentially transform how AI and copyright work

Dinusha Mendis, Bournemouth University

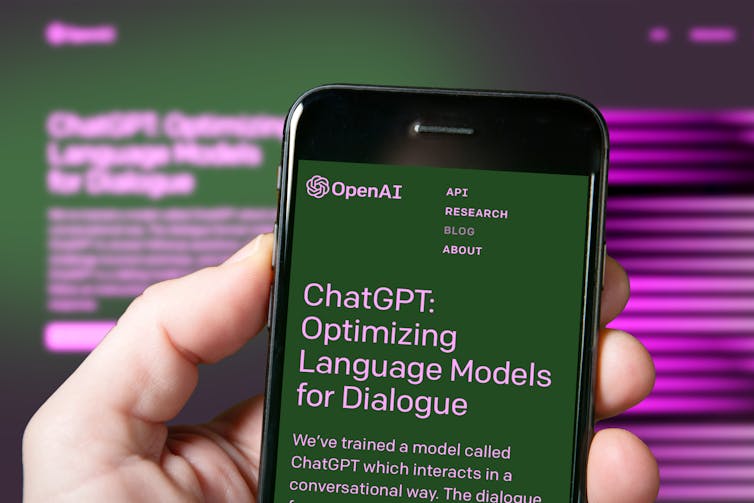

On December 27, 2023, the New York Times (NYT) filed a lawsuit in the Federal

District Court in Manhattan against Microsoft and OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT,

alleging that OpenAI had unlawfully used its articles to create artificial intelligence (AI) products.

Citing copyright infringement and the importance of independent journalism to democracy, the newspaper further alleged that even though the defendant, OpenAI, may have “engaged in wide scale copying from many sources, they gave Times content particular emphasis” in training generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools such as Generative Pre-Trained Transformers (GPT). This is the kind of technology that underlies products such as the AI chatbot ChatGPT.

The complaint by the New York Times states that OpenAI took millions of copyrighted news articles, in-depth investigations, opinion pieces, reviews, how-to guides and more in an attempt to “free ride on the Times’s massive investment in its journalism”.

In a blog post published by OpenAI on January 8, 2024, the tech company responded to the allegations by emphasising its support of journalism and partnerships with news organisations. It went on to say that the “NYT lawsuit is without merit”.

In the months prior to the complaint being lodged by the New York Times, OpenAI had entered into agreements with large media companies such as Axel-Springer and the Associated Press, although notably, the Times failed to reach an agreement with the tech company.

The NYT case is important because it is different to other cases involving AI and copyright, such as the case brought by the online photo library Getty Images against the tech company Stability AI earlier in 2023. In this case, Getty Images alleged that Stability AI processed millions of copyrighted images using a tool called Stable Diffusion, which generates images from text prompts using AI.

The main difference between this case and the New York Times one is that the newspaper’s complaint highlighted actual outputs used by OpenAI to train its AI tools. The Times provided examples of articles that were reproduced almost verbatim.

Use of material

The defence available to OpenAI is “fair use” under the US Copyright Act 1976, section 107. This is because the unlicensed use of copyright material to train generative AI models can serve as a “transformative use” which changes the original material. However, the complaint from the New York Times also says that their chatbots bypassed the newspaper’s paywalls to create summaries of articles.

Even though summaries do not infringe copyright, their use could be used by the New York Times to try to demonstrate a negative commercial impact on the newspaper – challenging the fair use defence.

This case could ultimately be settled out of court. It is also possible that the Times’ lawsuit was more a negotiating tactic than a real attempt to go all the way to trial. Whichever way the case proceeds, it could have important implications for both traditional media and AI development.

It also raises the question of the suitability of current copyright laws to deal with AI. In a submission to the House of Lords communications and digital select committee on December 5, 2023, OpenAI claimed that “it would be impossible to train today’s leading AI models without copyrighted materials”.

It went on to say that “limiting training data to public domain books and drawings created more than a century ago might yield an interesting experiment but would not provide AI systems that meet the needs of today’s citizens”.

Looking for answers

The EU’s AI Act –- the world’s first AI Act –- might give us insights into some future directions. Among its many articles, there are two provisions particularly relevant to copyright.

The first provision titled, “Obligations for providers of general-purpose AI

models” includes two distinct requirements related to copyright. Section 1(C)

requires providers of general-purpose AI models to put in place a policy to respect EU copyright law.

Section 1(d) requires providers of general purpose AI systems to draw up and make publicly available a detailed summary about content used for training AI systems.

While section 1(d) raises some questions, section 1(c) makes it clear that any use of copyright protected content requires the authorisation of the rights holder concerned unless relevant copyright exceptions apply. Where the rights to opt out has been expressly reserved in an appropriate manner, providers of general purpose AI models, such as OpenAI, will need to obtain authorisation from rights holders if they want to carry out text and data mining on their copyrighted works.

Even though the EU AI Act may not be directly relevant to the New York Times complaint against OpenAI, it illustrates the way in which copyright laws will be designed to deal with this fast-moving technology. In future, we are likely to see more media organisations adopting this law to protect journalism and creativity. In fact, even before the EU AI Act was passed, the New York Times blocked OpenAI from trawling its content. The Guardian followed suit in September 2023 – as did many others.

However, the move did not allow material to be removed from existing training

data sets. Therefore, any copyrighted material used by the training models up until then would have been used in OpenAI’s outputs –- which led to negotiations between the New York Times and OpenAI breaking down.

With laws such as those in the EU AI Act now placing legal obligations on general purpose AI models, their future could look more constrained in the way that they use copyrighted works to train and improve their systems. We can expect other jurisdictions to update their copyright laws reflecting similar provisions to that of the EU AI Act in an attempt to protect creativity. As for traditional media, ever since the rise of the internet and social media, news outlets have been challenged in drawing readers to their sites and generative AI has simply exacerbated this issue.

This case will not spell the end of generative AI or copyright. However, it certainly raises questions for the future of AI innovation and the protection of creative content. AI will certainly continue to grow and develop and we will continue to see and experience its many benefits. However, the time has come for policymakers to take serious note of these AI developments and update copyright laws, protecting creators in the process.![]()

Dinusha Mendis, Professor of Intellectual Property and Innovation Law; Director Centre for Intellectual Property Policy and Managament (CIPPM), Bournemouth University, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dr. Ashraf cited on ‘Modest Fashion’ in The Guardian

Dr. Ashraf cited on ‘Modest Fashion’ in The Guardian NIHR-funded research launches website

NIHR-funded research launches website Academics write for newspaper in Nepal

Academics write for newspaper in Nepal New paper published on disability in women & girls

New paper published on disability in women & girls Global Consortium for Public Health Research 2025

Global Consortium for Public Health Research 2025 MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published

Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published Horizon Europe 2025 Work Programme pre-Published

Horizon Europe 2025 Work Programme pre-Published Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease