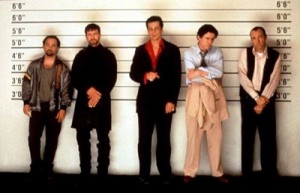

Facial composites are computerised visual likenesses, created by witnesses and victims of crimes, to resemble perpetrators. These images are released to the public in the course of an appeal, in the hope that someone familiar with the offender will report their identification to the police. While facial composites are only constructed in situations where the offender is unfamiliar to the victim and the offence serious, recent statistics show that upwards of 2,500 criminal investigations have made use of these images since 2013.

In this month’s Café Scientifique, Dr Emma Portch discussed how researchers can work collaboratively with forensic practitioners to improve the recognisability of these images. Emma highlighted that researchers can influence three separate stages of the composite construction process: (1) pre-construction cognitive interview techniques, (2) construction mechanics, and (3) post-production display of images.

Do construction systems mimic the way in which humans recognise unfamiliar faces? Emma detailed the difference between feature-based and holistic computerised composite systems. While feature-based systems require the witness to piece together a likeness, by selecting and editing from a database of individual photographed features (e.g. noses and mouths), holistic systems allow the witness to select whole-face representations, with selections bred together to preserve important configural similarities (i.e. the relative distances between features). Emma described how holistic systems better mirror the way in which we recognise faces in everyday life and demonstrated how further enhancement techniques can be used to boost the accuracy of images created this way (e.g. removing or blurring external facial features).

Are facial descriptions detrimental to subsequent facial recognition? Descriptions of the offender’s face are often critical to the process of composite construction and ACPO stipulate that composites should not be created if the witness cannot provide one. However, Emma revealed that providing a detailed facial description can sometimes make it more difficult to recognise when a composite has reached a good level of visual likeness. This so-called verbal overshadowing effect may arise as providing a verbal description of the face instates a suboptimal feature-based processing style, at odds with the holistic style needed to recognise that a composite well-resembles the offender. Emma discussed ways to alleviate verbal overshadowing, specifically focusing on promising results with a newer type of holistic interviewing.

How can we ensure that facial composites are recognised by those familiar with the offender? Composites are a useful investigative tool insofar as they can be identified by officers and members of the public familiar with the offender. Emma outlined the importance of post-production of images prior to media release, describing how different techniques could be used to occlude commonly error-prone regions of the image, and upregulate distinctive and accurate regions, respectively.

Dr Emma Portch reflects on her experience of speaking at Cafe Scientifique: ‘Public engagement is a vital exercise for communicating research findings to those who benefit from it most. The Café Scientifique team organised an excellent event and the attendees keep me on my toes with interesting and insightful questions and discussion’.

The next Café Scientifique will take place at Café Boscanova on Tuesday 5 November from 7:30pm until 9pm (doors open at 6:30pm)

There’s no need to register, make sure you get there early though as seats fill up fast!

Find out more about Café Scientifique and sign up to our mailing list to hear about other research events: www.bournemouth.ac.uk/cafe-sci

If you have any questions please do get in touch You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter

Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh

Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh Exploring Embodied Research: Body Map Storytelling Workshop & Research Seminar

Exploring Embodied Research: Body Map Storytelling Workshop & Research Seminar Marking a Milestone: The Swash Channel Wreck Book Launch

Marking a Milestone: The Swash Channel Wreck Book Launch No access to BRIAN 5-6th February

No access to BRIAN 5-6th February ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease