Dr Henry Ngenyam Bang writes for The Conversation about the potential dangers associated with crater lakes located in a region of volcanic activity in Cameroon…

Cameroon’s ‘exploding’ lakes: disaster expert warns deadly gas release could cause another tragedy

Photo by Thierry Orban/Sygma via Getty Images

Henry Ngenyam Bang, Bournemouth University

A sudden change on 29 August 2022 in the colour and smell of Lake Kuk, in north-west Cameroon, has caused anxiety and panic among the local residents. Fears are driven by an incident that happened 36 years ago at Lake Nyos, just 10km away.

On 21 August 1986, Lake Nyos emitted lethal gases (mainly carbon dioxide) that suffocated 1,746 people and around 8,300 livestock. It wasn’t the first incident like this. Two years earlier, Lake Monoum, about 100km south-west of Lake Nyos, killed 37 people.

Photo by Eric Bouvet via Getty Images

Research into the cause of the Lake Nyos disaster concluded that carbon dioxide gas – released from the Earth’s mantle – had been accumulating at the bottom of the lake for centuries. A sudden disturbance of the lake’s waters due to a landslide resulted in a sudden release of around 1.24 million tonnes of carbon dioxide gas.

Survivors briefly heard a rumbling sound from Lake Nyos before an invisible gas cloud emerged from its depths. It killed people, animals, insects and birds along its path in the valley before dispersing into the atmosphere where it became harmless.

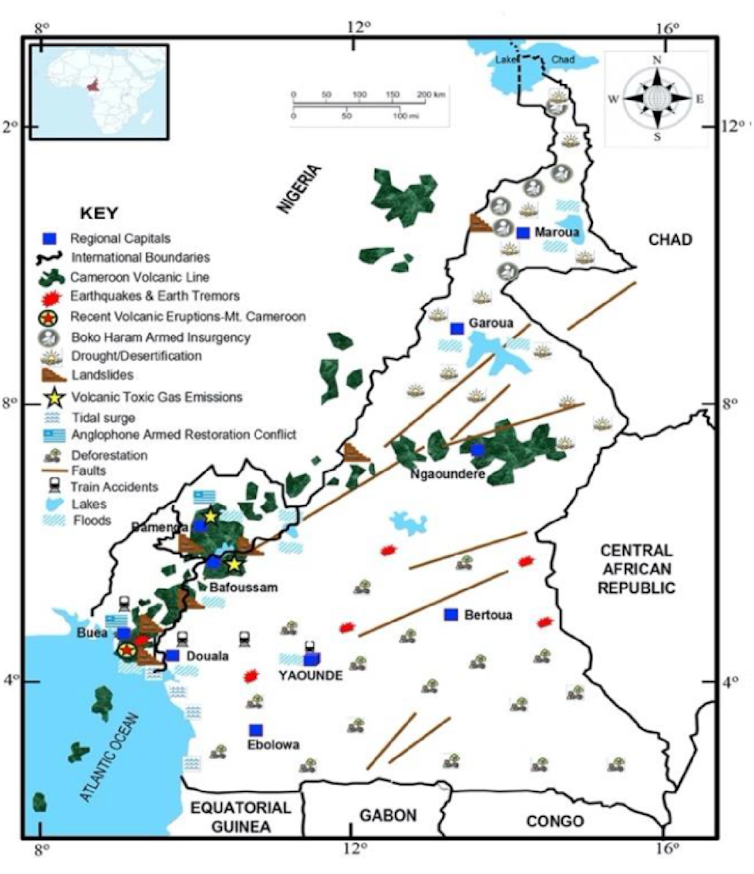

Both Kuk and Nyos are crater lakes located in a region of volcanic activity known as the Cameroon Volcanic Line. And there are 43 other crater lakes in the region that could contain lethal amounts of gases. Other lakes around the world that pose a similar threat include Lake Kivu at the border of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lake Ngozi in Tanzania and Lake Monticchio in Italy.

After Lake Nyos erupted, its water turned a deep red colour and survivors reported the smell of rotten eggs. These are the same characteristics to have recently manifested at Lake Kuk. The change in colour of Lake Nyos was only noticed after the gas burst.

In an official press release, heavy rainfall was linked to the odour and change in colour of Lake Kuk. The tens of thousands of people living around the lake were urged to “remain calm while being vigilant to continuously inform the administration of any other incident noted”.

As a geologist and disaster management expert, I believe that not enough is being done to address and manage the potential danger from crater lakes in the region.

Through my experience and research I’ve identified several key steps that policymakers must take to prevent another tragedy from happening.

Preventing disaster

To start with, it’s important to know which lakes are at risk of “exploding”.

Initial checks in some of the lakes were done more than 30 years ago and not thoroughly – it was just one team and on one occasion. Further investigations and regular monitoring are required.

Currently it’s believed that, of the 43 crater lakes on Cameroon’s Volcanic Line, 13 are deep and large enough to contain lethal quantities of gases. Although 11 are considered to be relatively safe, two (Lakes Enep and Oku) are dangerous.

Research has revealed that the thermal profile (how temperature changes with depth), quantity of dissolved gases, surface area or water volume and depth are key indicators of the potential for crater lakes to store large quantities of dangerous gases.

The factors that lead to the greatest risk include: high quantities of dissolved gases, held under high pressures, at great depths, in lakes with large volumes of water. They are at an even greater risk of explosion when the lakes sit in wide or large craters where there are disturbances.

The two lakes that caused fatalities (Nyos and Monoum) are deep and have thermal profiles that increase with depth. Other lakes are too shallow (less than 40 metres) and have uniform thermal profiles, indicating they do not contain large amounts of gases.

Investigating all the crater lakes in Cameroon would be a logistical challenge. It would require significant funding, a diverse scientific team, technical resources and transportation to the lakes. Since most of the crater lakes are in remote areas with poor communication network (no roads, rail or airports), it would take a couple of years for the work to be completed.

Since Cameroon has many potentially dangerous crater lakes, it is unsatisfactory that 36 years after the Lake Nyos disaster, not much has been done to mitigate the risks in other gas-charged hazardous lakes.

Managing dangerous lakes

Lake Kuk was checked shortly after the 1986 Lake Nyos disaster and found not to contain excess carbon dioxide. Its relatively shallow depth and surface area means the risk of gas being trapped in large quantities is low.

Nevertheless, authorities should have immediately restricted access to Lake Kuk pending a thorough onsite investigation. The official press release urging calm was sent just one day after the incident was reported. It’s not possible that a scientist could have carried out a physical examination of the lake. The release said that rainfall was responsible for the changes, but this will be based on assumptions.

Lake Kuk might be considered safe, but due to the dynamic and active nature of the Cameroon Volcanic Line, there is a possibility that volcanic gases can seep into the lake at any moment.

An onsite scientific investigation would determine with certainty the abnormal behaviour of Lake Kuk. Keeping people away from the lake until a swift and credible investigation had been done would be the most rational decision.

An additional step would be for a carbon dioxide detector to be installed near Lake Kuk and other potentially dangerous crater lakes. This would serve as an early warning system for lethal gas releases.

A carbon dioxide early warning system is designed to detect high concentrations of gases in the atmosphere and to produce a warning sound. Upon hearing the sound, people are expected to run away from the lake and onto higher ground. After the Lake Nyos disaster, carbon dioxide detectors and warning systems were installed near Lakes Nyos and Monoum. Nevertheless, no simulation has been conducted to determine their effectiveness.

The Directorate of Civil Protection is the designated agency responsible for coordinating disaster risk management in Cameroon. The agency should liaise with other stakeholders in the government and private sector to ensure the safety of Cameroon’s dangerous lakes. If the authorities are not proactive, the Lake Nyos disaster scenario may repeat where thousands of people and livestock are suddenly killed.![]()

Henry Ngenyam Bang, Disaster Management Scholar, Researcher and Educator, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Prof Marahatta promoting BU-Nepal collaboration

Prof Marahatta promoting BU-Nepal collaboration 3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm

3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March

Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward?

Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward? ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease