Recently I attended the ARMA conference on Public Engagement with Research, as well as the H3 Symposium on Public Engagement as a Pathway to Impact. Whilst both events where filled with interesting case studies of public engagement ideas from around the UK, one key message stuck with me – we need to be supporting our academic community to be considering public engagement throughout the research life cycle.

The National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE) defines public engagement as:

“The myriad of ways in which the activity and benefits of higher education and research can be shared with the public. Engagement is by definition a two-way process, involving interaction and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit.”

For me the most important part of this definition is the reference to a two way process generating mutual benefit.

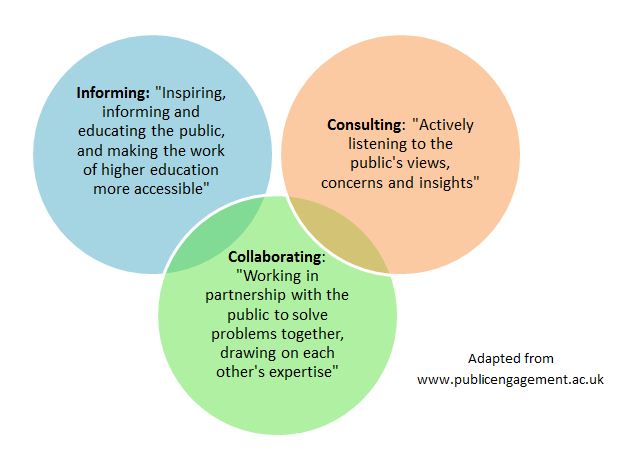

The NCCPE website is extensive and provides plenty of information on why public engagement is important, who to engage with, tips and ideas for events as well as training opportunities. They also talk about what the purpose of engagement is, summarised in the below diagram.

Dissemination of results at the end of a study is a common driver for wanting to engage the public, but actually, could you be doing more to engage with them earlier and as a result improve your study? Going back to the idea of mutual benefit and the above described purposes of engagement could you incorporate more than just “informing” within your research? The suggestion from the conference is to consider public engagement as part of the very beginning stages of your research proposal and build it into the research lifecycle from the start.

Two examples were given for incorporating public engagement earlier than the dissemination. The first of these was using a “citizen science” approach. Case studies included the Predatory Bird Monitoring Scheme which asks the public to send in any dead birds of prey they find to a lab where they can analyse the specimen, and Fresh Water Watch which globally sources water samples to investigate the health of fresh water eco systems. These were both cited as examples of published data sets and successful citizen science projects.

A second example given was the BBC’s WW2 People’s War archive. This was a project that ran in the early 2000’s that encourages WW2 veterans to share their stories and images via the website and create a record of their experiences. In addition to the website they also collected stories via the library network and dedicated events. As a result they now have a wealth of data and can maintain those memories that would otherwise have been lost.

Aside from being useful for data collection purposes the public have a lot to offer in terms of giving you new insights into research. “Consulting” as the NCCPE refer to it, could be talking to the public about what you have planned for a research study and listening to their ideas and questions as they come back. This makes your research relevant to the public and therefore maximises public benefit. At the University of Exeter they have formalised this approach through the development of PenPIG, or the Peninsula Patient Involvement Group. This is a group of patients and carers who volunteer their time to ensure research is developed based on the needs of the public. Could you apply the same principles by organising an event for local stakeholders whilst your planning your study?

So as you’re thinking about your future Festival of Learning event (deadline for proposals Friday 19th December) or considering your next research project consider how public engagement could play a part at all stages of the research lifecycle. If you’d like to discuss this further please do get in touch.

Nursing Research REF Impact in Nepal

Nursing Research REF Impact in Nepal Fourth INRC Symposium: From Clinical Applications to Neuro-Inspired Computation

Fourth INRC Symposium: From Clinical Applications to Neuro-Inspired Computation ESRC Festival of Social Science 2025 – Reflecting back and looking ahead to 2026

ESRC Festival of Social Science 2025 – Reflecting back and looking ahead to 2026 3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Cookies – Tuesday 13 January 10-11am

3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Cookies – Tuesday 13 January 10-11am Dr. Chloe Casey on Sky News

Dr. Chloe Casey on Sky News ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published

Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease