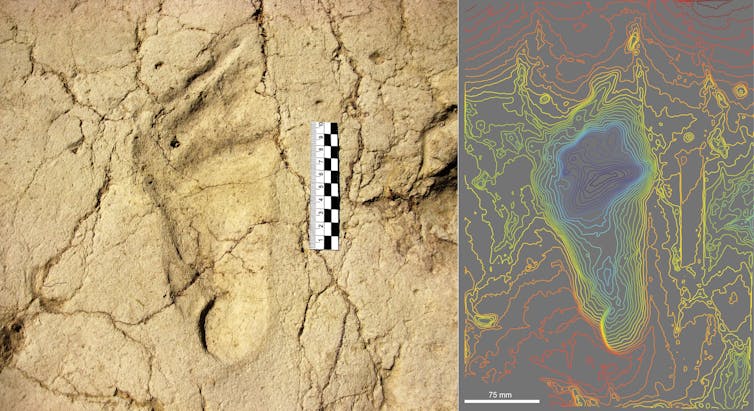

Footprint from 700,000 years ago. Matthew Bennett, Author provided

By Professor Matthew Bennett and Dr Sally Reynolds.

Western society has a rather specific view of what a good childhood should be like; protecting, sheltering and legislating to ensure compliance with it. However, perceptions of childhood vary greatly with geography, culture and time. What was it like to be a child in prehistoric times, for example – in the absence of toys, tablets and television?

In our new paper, published in Scientific Reports, we outline the discovery of children’s footprints in Ethiopia which show how children spent their time 700,000 years ago.

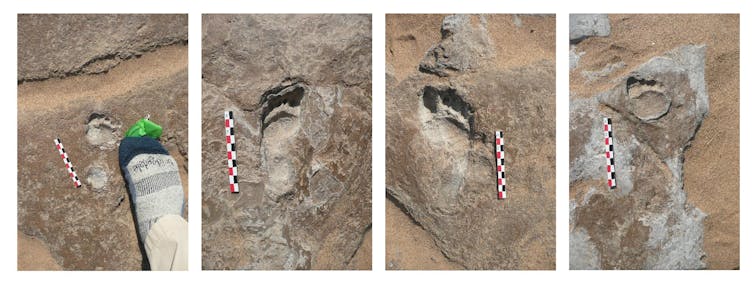

We first came across the question of what footprints can tell us about past childhood experiences a few years back while studying some astonishingly beautiful children’s footprints in Namibia, just south of Walvis Bay. In archaeological terms the tracks were young, dating only from around 1,500 years ago. They were made by a small group of children walking across a drying mud surface after a flock of sheep or goats. Some of these tracks were made by children as young as three-years-old in the company of slightly older children and perhaps young adolescents.

Namibian footprints. Matthew Bennett, Author provided

The detail in these tracks, preserved beneath the shifting sands of the Namibian Sand Sea, is amazing, and the pattern of footfall – with the occasional skip, hop and jump – shows they were being playful. The site also showed that children were trusted with the family flock of animals from an early age and, one assumes, they learnt from that experience how to function as adults were expected to within that culture.

No helicopter parents

But what about the childhood of our earlier ancestors – those that came before anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens)? Children’s tracks by Homo antecessor (1.2m to 800,000 years ago) were found at Happisburgh in East Anglia, a site dating to a million years ago. Sadly though, these tracks leave no insight into what these children were doing.

Reconstruction of Homo Heidelbergensis. Jose Luis Martinez Alvarez/wikipedia, CC BY-SA

This assemblage of tracks is capped by an ash flow from a nearby volcano which has been dated to 700,000 years ago. The ash flow was deposited shortly after the tracks were left, although we don’t know precisely how soon after. The tracks are not as anatomically distinct as those from Namibia but they are smaller and may have been made by children as young as one or two, standing in the mud while their parents and older siblings got on with their activities. This included knapping the stone tools with which they butchered the carcass of the hippo.

The findings create a unique and momentary insight into the world of a child long ago. They clearly were not left at home with a babysitter when the parents were hunting. In the harsh savannah plains of the East African Rift Valley, it was natural to bring your children to such daily tasks, perhaps so they could observe and learn.

This is not surprising, when one considers the wealth of ethnographic evidence from modern, culturally distinct human societies. Babies and children are most often seen as the lowliest members of their social and family groups. They are often expected to contribute to activities that support the mother, and the wider family group, according to their abilities. In many societies, small boys tend to help with herding, while young girls are preferred as babysitters. Interestingly, adult tools – like axes, knives, machetes, even guns – are often freely available to children as a way of learning.

Artistic impression of scene at Melka Kunture. Matthew Bennett, Author provided

So, if we picture the scene at Melka Kunture, the children observing the butchery were probably allowed to handle stone tools and practice their skills on discarded pieces of carcass while staying out of the way of the fully-occupied adults. This was their school room, and the curriculum was the acquisition of survival skills. There was little time or space to simply be a child, in the sense that we would recognise today.

This was likely the case for a very long time. The Monte Hermoso Human Footprint Site in Argentina (roughly 7,000-years-old) contains predominantly small tracks (of children and women) preserved in coastal sediments and it has been suggested that the children may have played an important role in gathering seafood or coastal resources. Similarly, most of the tracks in the Tuc d’Audoubert Cave in France (15,000-years-old) are those of children and the art there is striking. Perhaps they were present when it was carved and painted?

However, these observations contrasts to the story that emerged last year based on tracks from the older Homo Homo erectus (1.5m-year-old) at Ileret, located further south in the Rift Valley, just within the northern border of Kenya. Here the tracks have been interpreted as the product of adult hunting groups moving along a lake shore, rather than a domestic scene such as that at Melka Kunture. However, these scenes aren’t mutually exclusive and both show the power of footprints to provide a snapshot into past hominin behaviour.

But it does seem like the overwhelming parenting lesson from the distant past is that children had more responsibilities, less adult supervision and certainly no indulgence from their parents. It is a picture of a childhood very different from our own, at least from the privileged perspective of life in Western society.

Matthew Robert Bennett, Professor of Environmental and Geographical Sciences, Bournemouth University and Sally Christine Reynolds, Senior Lecturer in Hominin Palaeoecology, Bournemouth University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Julie Robson from the Department of Marketing (FoM) has co-authored an article published today in The Conversation about unpaid student placements and debt.

Julie Robson from the Department of Marketing (FoM) has co-authored an article published today in The Conversation about unpaid student placements and debt.

Expand Your Impact: Collaboration and Networking Workshops for Researchers

Expand Your Impact: Collaboration and Networking Workshops for Researchers Visiting Prof. Sujan Marahatta presenting at BU

Visiting Prof. Sujan Marahatta presenting at BU 3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm

3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching

UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease