Earlier this year a large number of academics across the UK completed the biennial Principal Investigators and Research Leaders Survey (PIRLS) run by Vitae. Looking through the responses from BU academics I was interested to note a number of conflicting responses on the theme of research vs education and which is more valued at BU, as well as in the sector as a whole. Some respondents reported that the primary focus is education, enhancing the student experience, student administration, etc. whilst other felt that research activity is valued ahead of education and that institutional developments over the past ten years have been to the advantage of research.

Earlier this year a large number of academics across the UK completed the biennial Principal Investigators and Research Leaders Survey (PIRLS) run by Vitae. Looking through the responses from BU academics I was interested to note a number of conflicting responses on the theme of research vs education and which is more valued at BU, as well as in the sector as a whole. Some respondents reported that the primary focus is education, enhancing the student experience, student administration, etc. whilst other felt that research activity is valued ahead of education and that institutional developments over the past ten years have been to the advantage of research.

From an internal perspective I found this interesting for two main reasons:

1. The BU strategy focuses on fusion – the equal importance of education, research and professional practice and how these support and strengthen each other.

2. Is it a case of research vs education, i.e. two separate activities each vying for time, or are these mutually supportive activities?

Looking externally, however, it is clear that over the past 50 or so years the sector at large has enshrined the research-oriented university and therefore the role of the research-oriented academic as an ideal model. We can see this in the way the majority of the league tables are constructed, with research metrics playing a dominant role. We can see it in the stratification of universities with the ‘elite’ institutions being those that are considered research-intensive. And we can see it in the concentration of funding and sponsorship for research that flows into these institutions, enabling them to remain research orientated.

But what are the consequences of this? How does this impact on the HE sector at large?

For starters, it has created a stratified hierarchy among institutions and within the academy where arguably none need exist. Academia has a multitude of different missions that need to be addressed by the profession as a whole. The focus on research as the holy grail devalues the breadth and diversity of universities and undermines the role they all play in advancing society.

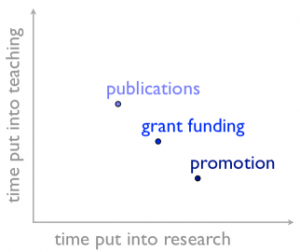

Secondly there is a link between the rise of the importance of the research intensive university and the increased managerialism of higher education, i.e. that higher education and research must be efficient and productive and measurable. This as a policy in itself is not a bad thing – high quality teaching depends on research, reputation is built on scholarly output, and reputation influences an institution’s ability to attract students and staff. This favours research-intensive institutions that earn significant amounts of income and can ensure research activity forms a central part (and in some cases the majority) of academics’ roles. There are, however, few institutions where the research model fits and works and it becomes detrimental to those not in the top few as it causes greater tensions between teaching (the bulk of the work), research (usually a small portion of work) and time/energy. I don’t believe that life is rosy for those academics in the top tier of institutions – the pressures placed upon them to perform, bring in more and more funding, produce better quality papers in the top journals, etc. must be enormous. But that is a different type of pressure to that experienced in universities such as BU where the tension between teaching and research and time are very real. Goffman described this tension by stating that it makes an academic career “perhaps as complex and troubled as the moral career of the mental patient”.

Secondly there is a link between the rise of the importance of the research intensive university and the increased managerialism of higher education, i.e. that higher education and research must be efficient and productive and measurable. This as a policy in itself is not a bad thing – high quality teaching depends on research, reputation is built on scholarly output, and reputation influences an institution’s ability to attract students and staff. This favours research-intensive institutions that earn significant amounts of income and can ensure research activity forms a central part (and in some cases the majority) of academics’ roles. There are, however, few institutions where the research model fits and works and it becomes detrimental to those not in the top few as it causes greater tensions between teaching (the bulk of the work), research (usually a small portion of work) and time/energy. I don’t believe that life is rosy for those academics in the top tier of institutions – the pressures placed upon them to perform, bring in more and more funding, produce better quality papers in the top journals, etc. must be enormous. But that is a different type of pressure to that experienced in universities such as BU where the tension between teaching and research and time are very real. Goffman described this tension by stating that it makes an academic career “perhaps as complex and troubled as the moral career of the mental patient”.

I’m not sure what the answer is that gives this a happy ending. It is likely there isn’t one and the tensions will remain, but BU’s fusion strategy and the new academic career framework should ensure that, internally at least, all activities are equally valued. None of the information in this post is new, however, sometimes it does us good to step back from the precipice and acknowledge the tensions before deciding the next step. We need to continue to play the game of the research-oriented university as this is what the sector is increasingly basing itself upon, but we must do it in a way that is right for BU and doesn’t tie us all up in knots. Any thoughts?

I’m not sure what the answer is that gives this a happy ending. It is likely there isn’t one and the tensions will remain, but BU’s fusion strategy and the new academic career framework should ensure that, internally at least, all activities are equally valued. None of the information in this post is new, however, sometimes it does us good to step back from the precipice and acknowledge the tensions before deciding the next step. We need to continue to play the game of the research-oriented university as this is what the sector is increasingly basing itself upon, but we must do it in a way that is right for BU and doesn’t tie us all up in knots. Any thoughts?

The role of a university has been debated since the nineteenth century. In 1852 Cardinal Newman wrote that the sole function of a university was to teach universal knowledge, embodying the idea of ‘the learning university’. Newman believed that knowledge is valuable and important for its own sake and not just for its perceived use to society (this is very different from the current thinking on the importance of research impact, public accountability and the value of research findings to society at large, issues which I imagine Newman would have thought of as irrelevant!). There was not a great deal in Newman’s work about the importance of research in a university, but research was beginning to play the starring role in mainland Europe where Prussian education minister Wilhelm von Humboldt wrote of the concept of ‘the research university’ and eventually set up the Humboldt University of Berlin. After the Napoleonic Wars, von Humboldt’s view was that the research university was a tool for national rebuilding through the prioritisation of graduate research over undergraduate teaching. This model soon became the blueprint for the rest of Europe, the United States and Japan. Arguably the Russell Group universities are today still structured in a similar way to that envisaged by von Humboldt two hundred years ago.

The role of a university has been debated since the nineteenth century. In 1852 Cardinal Newman wrote that the sole function of a university was to teach universal knowledge, embodying the idea of ‘the learning university’. Newman believed that knowledge is valuable and important for its own sake and not just for its perceived use to society (this is very different from the current thinking on the importance of research impact, public accountability and the value of research findings to society at large, issues which I imagine Newman would have thought of as irrelevant!). There was not a great deal in Newman’s work about the importance of research in a university, but research was beginning to play the starring role in mainland Europe where Prussian education minister Wilhelm von Humboldt wrote of the concept of ‘the research university’ and eventually set up the Humboldt University of Berlin. After the Napoleonic Wars, von Humboldt’s view was that the research university was a tool for national rebuilding through the prioritisation of graduate research over undergraduate teaching. This model soon became the blueprint for the rest of Europe, the United States and Japan. Arguably the Russell Group universities are today still structured in a similar way to that envisaged by von Humboldt two hundred years ago. Moving into the twentieth century and we come across American educationalist Abraham Flexner who wrote of ‘the modern university’. In Flexner’s view universities had a responsibility to pursue excellence, with academic staff being able to seamlessly move from the research lab to the classroom and back again. The pursuit of excellence features in many universities strategies, and sounds very similar to the message conveyed by the REF team as part of the REF2014 guidance. The union of research and education also sounds similar to the current structure of many UK universities.

Moving into the twentieth century and we come across American educationalist Abraham Flexner who wrote of ‘the modern university’. In Flexner’s view universities had a responsibility to pursue excellence, with academic staff being able to seamlessly move from the research lab to the classroom and back again. The pursuit of excellence features in many universities strategies, and sounds very similar to the message conveyed by the REF team as part of the REF2014 guidance. The union of research and education also sounds similar to the current structure of many UK universities. The creation and sharing of new knowledge and new ideas has become the principal purpose of many modern universities. In Northern and Western Europe and North America the university has become the key producer of knowledge (through research) and the key sharer of knowledge (through teaching). The University of Bristol’s Vice-Chancellor Professor Eric Thomas claims that universities are the knowledge engines of our society having produced the vast majority of society’s breakthroughs and innovations, such as: the computer, the web, the structure of DNA, Dolly the Sheep, and the fibre optic cable. Where would we be without these breakthroughs, and would they have come about so quickly without university research?

The creation and sharing of new knowledge and new ideas has become the principal purpose of many modern universities. In Northern and Western Europe and North America the university has become the key producer of knowledge (through research) and the key sharer of knowledge (through teaching). The University of Bristol’s Vice-Chancellor Professor Eric Thomas claims that universities are the knowledge engines of our society having produced the vast majority of society’s breakthroughs and innovations, such as: the computer, the web, the structure of DNA, Dolly the Sheep, and the fibre optic cable. Where would we be without these breakthroughs, and would they have come about so quickly without university research?

Second NIHR MIHERC meeting in Bournemouth this week

Second NIHR MIHERC meeting in Bournemouth this week Dr. Ashraf cited on ‘Modest Fashion’ in The Guardian

Dr. Ashraf cited on ‘Modest Fashion’ in The Guardian NIHR-funded research launches website

NIHR-funded research launches website MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published

Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published Horizon Europe 2025 Work Programme pre-Published

Horizon Europe 2025 Work Programme pre-Published Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease