Our blog Part 1 (posted on Friday May 15th) provided a very crude overview of the preliminary results from the survey we have launched to collate data on the impact of C-19 lockdown on the work-life balance of academics. This Part 2 focuses on differences between groups of respondents and identifying whether particular groups have been more negatively affected. We are yet to do any statistical tests on these data, so please consider differences between groups with care.

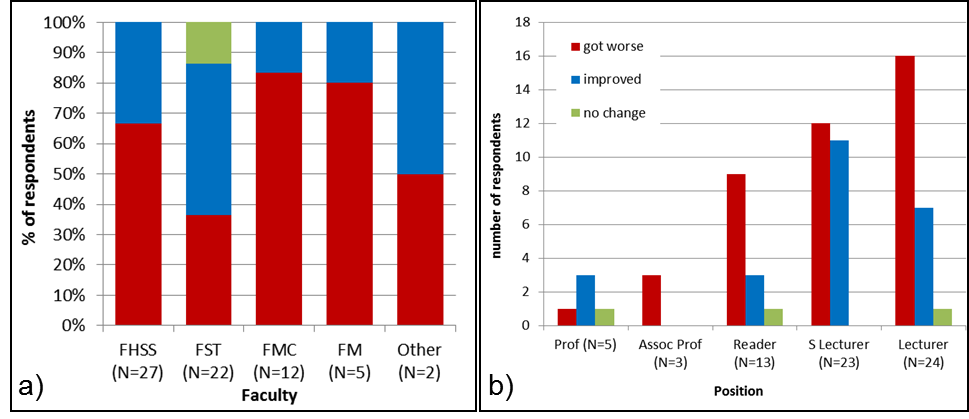

We have received 170 responses to date, 70 we could identify as being from BU staff (63 from female colleagues). If you have not yet contributed to this survey, you can still to do so here: https://bournemouth.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/impact-of-lockdown-on-academics, and please do share with your networks, as the survey is open to all academics. If you want us to be able to identify that you are BU staff, you will need to mention BU in one of the open questions. This research is a cross-faculty collaboration conducted by Sara Ashencaen Crabtree (FHSS), Ann Hemingway (FHSS) and myself (FST).

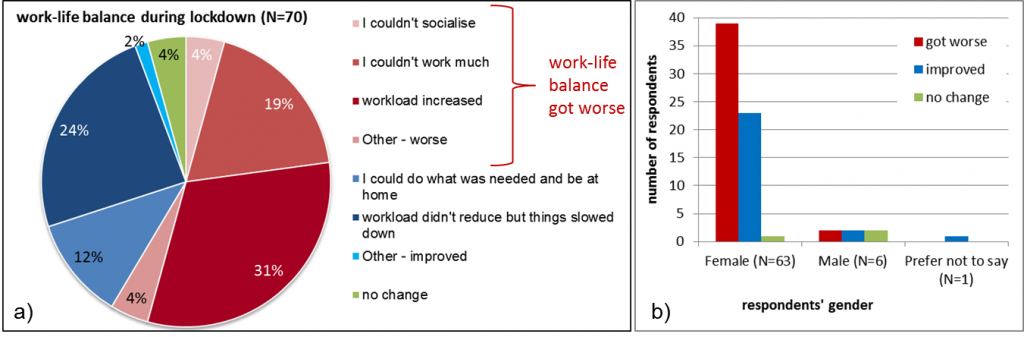

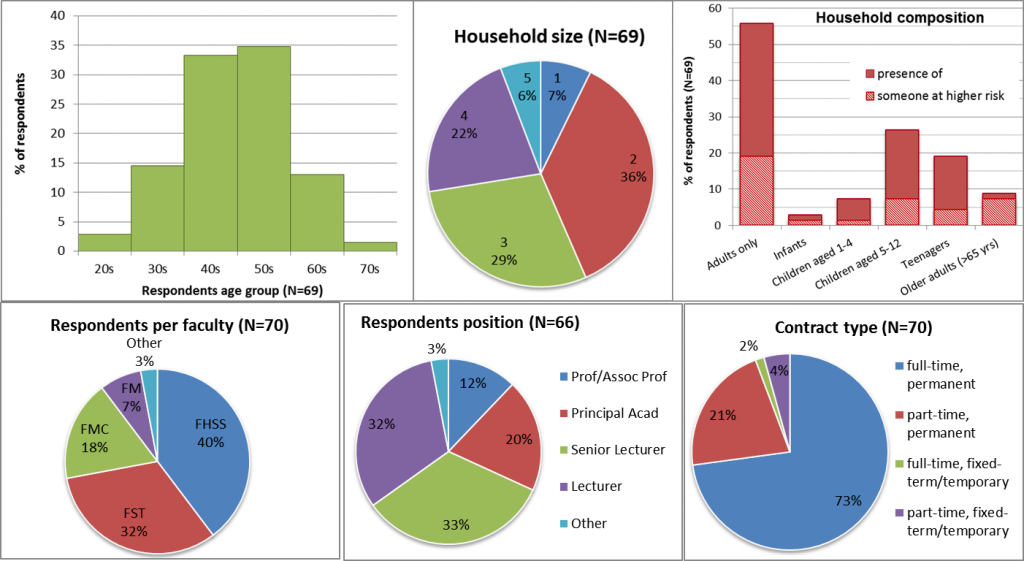

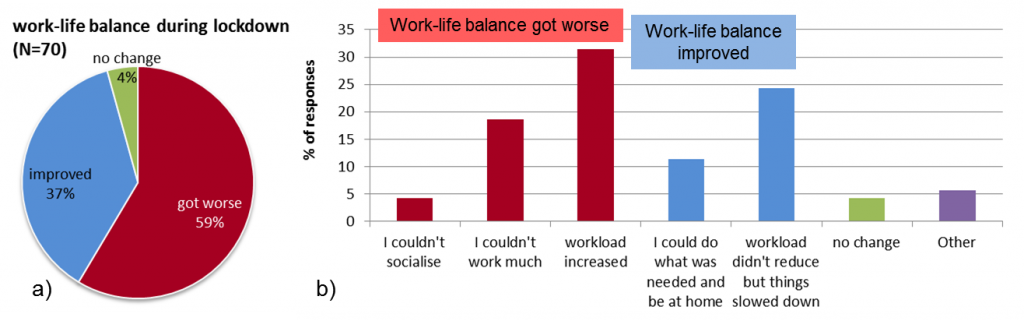

Work-life balance during lockdown got worse for the majority of respondents (59%) and improved for 37%. The most common reason for worsening or improving work-life balance were ‘workload increased’ (31%) and ‘I could do what was needed and be at home/with family’ (24%), respectively (Figure 1a). Although there are differences across gender (Figure 1b), any differences between male and female respondents should not be considered representative of the wider community due to the small number of male respondents.

Figure 1. Changes in work-life balance of respondents during Covid-19 lockdown and the selected reasons for identifying positive or negative change (a) and reported changes per gender of respondents (b). Blue shades indicate work-life balance improved and red shades indicate it worsened.

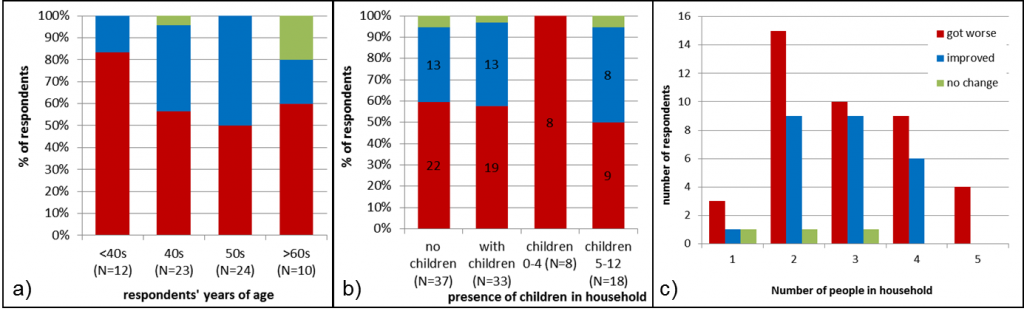

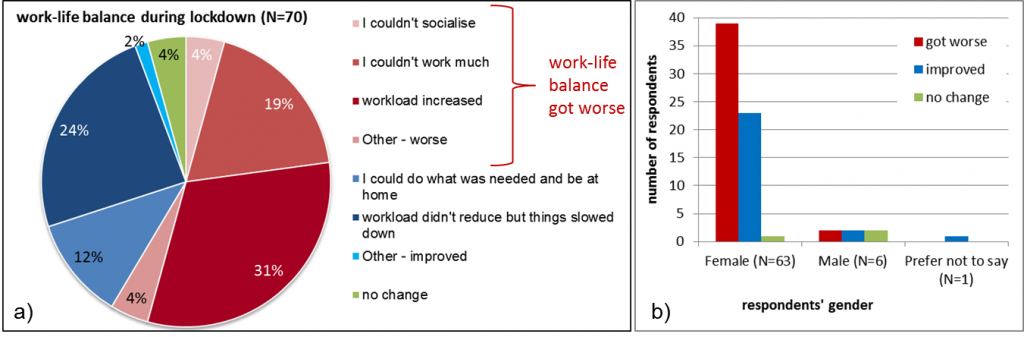

A higher proportion of academics under the age of 40 (82%) indicated that their work-life balance has worsened during lockdown when compared with other age groups (Figure 2a). Most of these academics reported that work-life balance worsened because they couldn’t work much. For academics in their 50s or older, the key reason for worsening of work-life balance was the increase in workload.

Figure 2. Changes in work-life balance of respondents during Covid-19 lockdown per age group (a); presence of children in the household (b) – the group ‘with children’ includes children ages 0-12 and teenagers; and household size (c).

Balancing work and childcare and/or homeschooling was mentioned as a negative effect on work-life balance during lockdown by 18% and 7% respectively. However, this does not seem to be the main cause affecting respondents under the age of 40, when responses between groups with and without children are compared. In fact, 87% of respondents in their 40s live in a household with children 12 years old or younger and yet the proportion of this age group reporting worsened work-life balance was lower (55%) than the proportion of respondents with no children (60%). However, respondents who live in a household with younger children seem to be more negatively affected.

All respondents (N=8) who live with children under the age of 5 years have reported that their work-life balance have worsened (Figure 2b), the majority indicated an increase in workload as the main reason. However, no major differences were found when comparing groups of respondents who live with children (all ages under 19 included) and households without children. Interestingly, a lower proportion of respondents who live with children aged 5-12 years report worse work-life balance (50%) than respondents who do not have children in their household (60%) (Figure 2b). Further, work-life balance has improved for a higher proportion of respondents who live in a household of three people (45%) than in other household sizes (<40%) (Figure 2c).

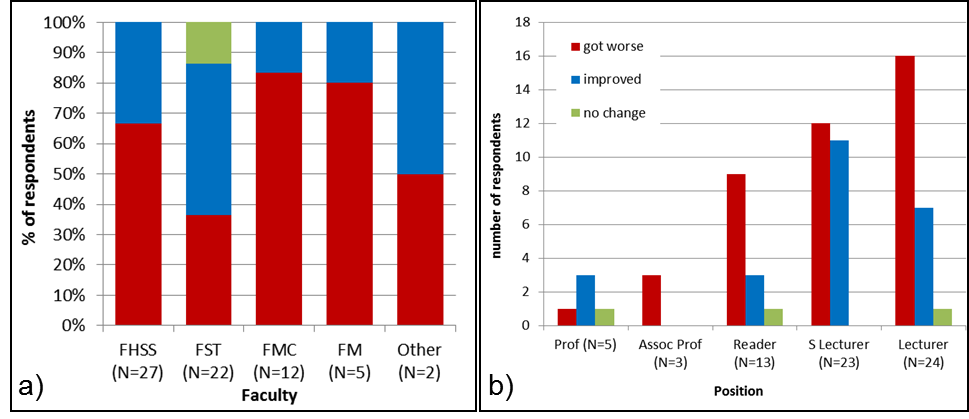

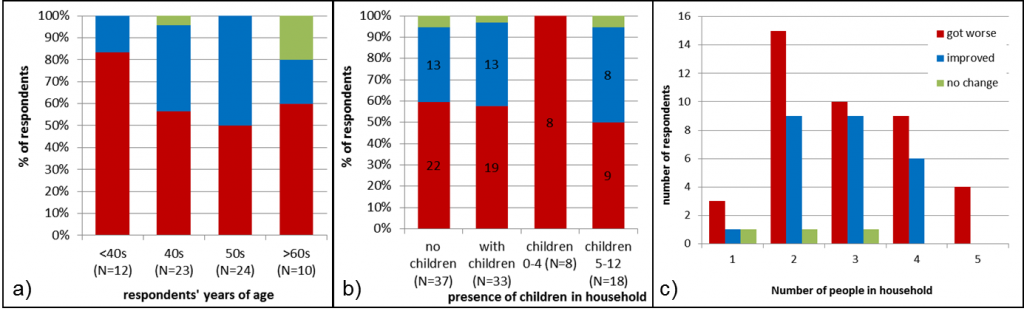

In all faculties, a higher number of respondents reported work-life balance getting worse than improving, except FST (Figure 3a), where work-life balance has improved for 50% of respondents and worsened for 36%. Professors were the only group with more respondents indicating work-life balance improved (50%) than worsened (25%); in contrast, all associate professors reported worsened work-life balance (Figure 3b), but the small sample in both groups may not be representative.

Figure 3. Changes in work-life balance of respondents during Covid-19 lockdown per faculty (a) and position (b).

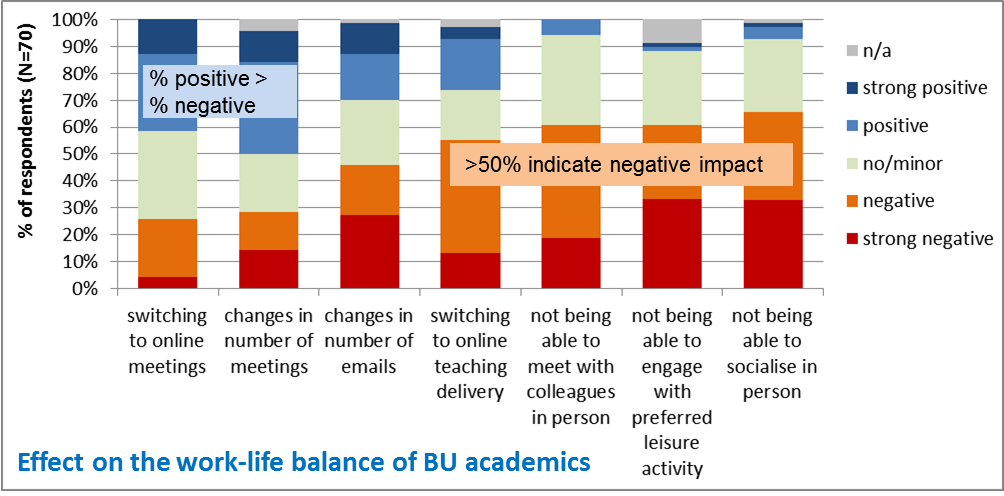

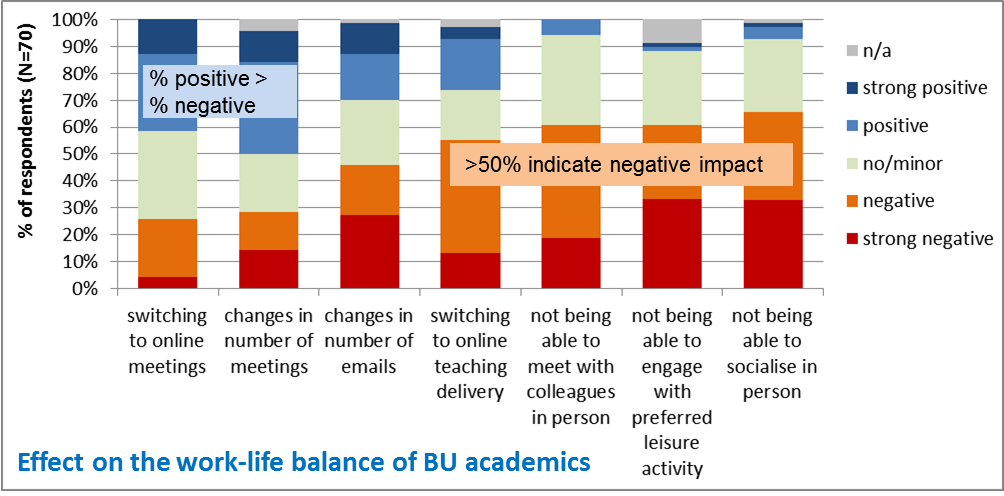

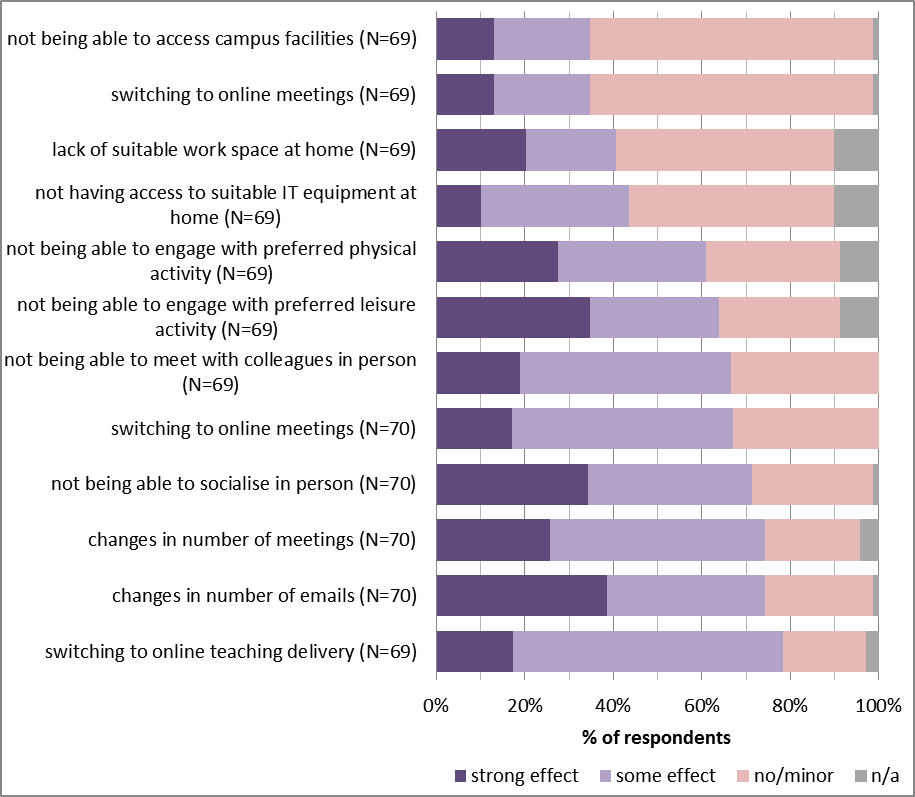

Switching to online teaching and not being able to meet with colleagues in person, socialise and engage with preferred leisure activity were the factors affecting negatively more than 50% of respondents (Figure 4).When lockdown restrictions are lifted, two of these factors (socialise and engage with preferred leisure activity) will have less effect on academics work-life balance, but more could be done to support colleagues negatively affected by the switch to online teaching and missing the contact with colleagues while working remotely.

More respondents have indicated a positive than negative impact from changes in the number of meetings and switching to online meetings emails (Figure 4). Fewer and more effective meetings were reported as the positive impacts. However, for some respondents, there are too many online meetings and they are getting tired of (avoidable) prolonged screen time (an effect that has been called Zoom fatigue). Therefore, guidance on how best to use, organise and participate in online meetings and how to manage and reduce screen time/tiredness may be useful.

Figure 4. The impact of selected factors on the work-life balance of respondents during lockdown.

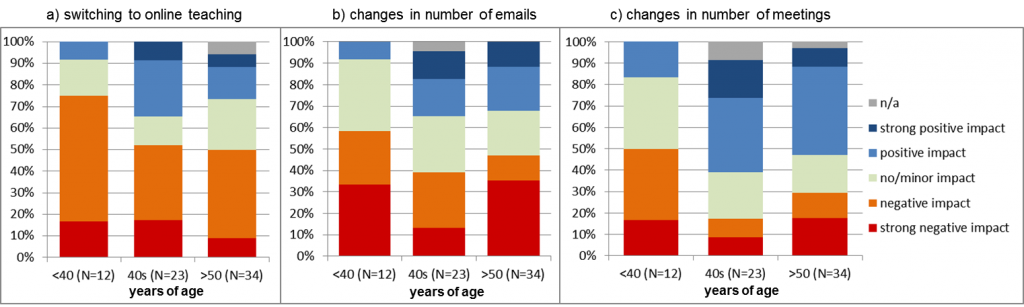

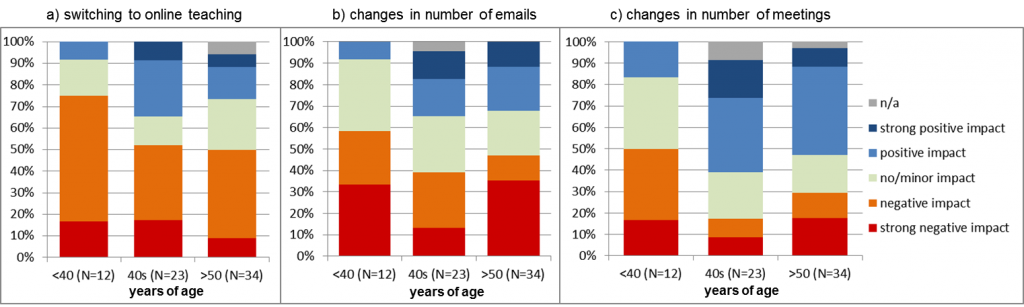

A considerably higher proportion of respondents under 40 years of age report negative effect from switching to online teaching (75%), change in the number of emails (58%) and changes in the number of meetings (50%) in relation to other age groups (Figure 5). This age group also shows lower proportion of staff indicating positive effect from these three factors.

Figure 5. Reported impact per age group from (a) switching to online teaching; (b) changes in number of emails; and (c) changes in number of meetings.

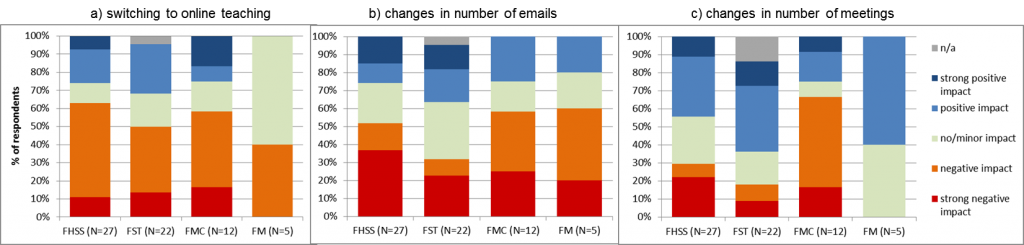

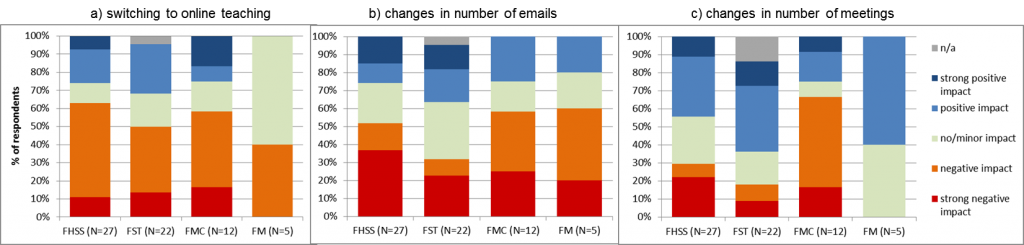

FMC is the only faculty with more than 50% of respondents reporting negative effect from switching to online teaching (58%), change in the number of emails (58%) and changes in the number of meetings (67%). FST and FM are the faculties with 50% of respondents reporting positive impact from changes in the number of meetings. FHSS has the largest proportion of respondents indicating negative effect from switching to online teaching (62%) and strong negative effect due to changes in the number of emails (54%). Increased number of emails from students has been reported, particularly by FHSS staff who support students who were asked to work for the NHS.

Figure 6. Reported impact per faculty from (a) switching to online teaching; (b) changes in number of emails; and (c) changes in number of meetings.

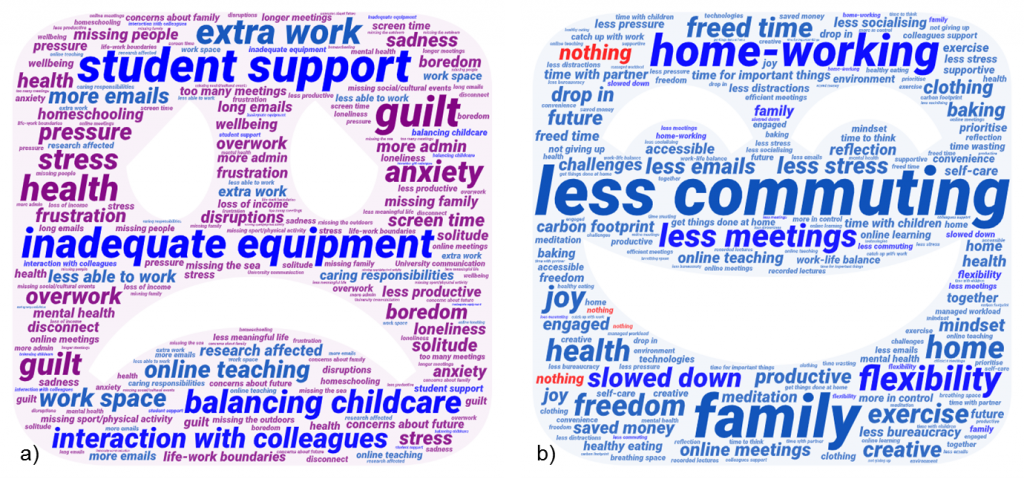

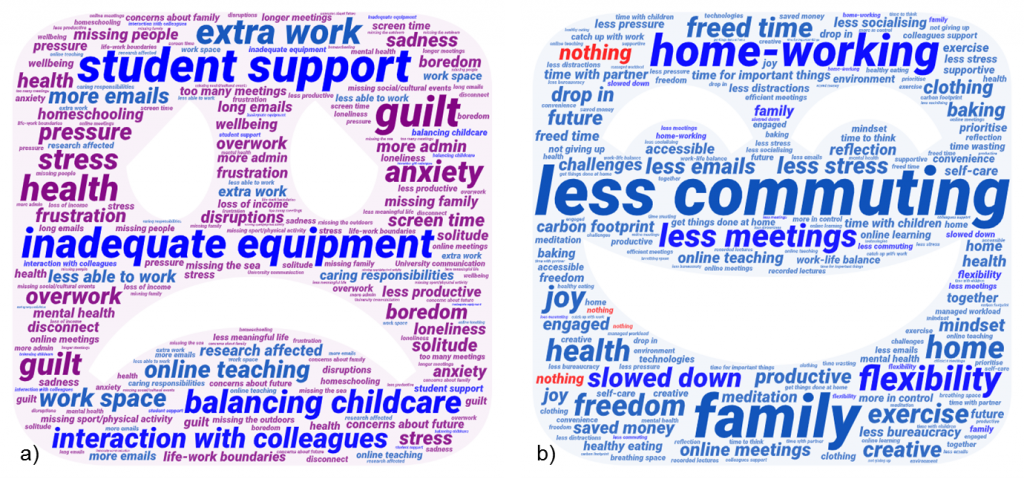

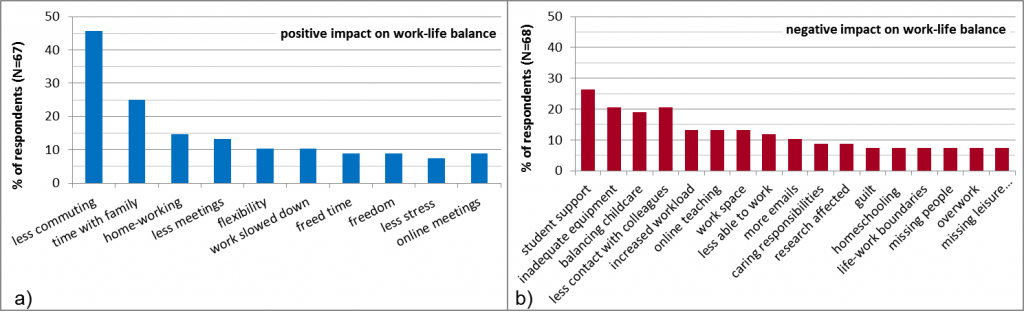

Figure 7 shows word clouds based on responses to the open questions asking for the two most important factors leading to negative and positive impacts on their work-life balance during lockdown. Increased demand for student support was the most cited negative factor (by 27% of respondents), followed by missing contact with colleagues and inadequate equipment (e.g. IT, desk, chair) and balancing childcare (19%). Less commuting or travel for work was the most cited factor affecting work-life balance positively (46% of respondents), followed by time with family (25%) and enjoying working from home (15%).

Figure 7. Word cloud showing how respondents expressed the negative (a) and positive (b) factors affecting their work-life balance during C-19 lockdown.

In responses to open questions, it is apparent that many negative aspects of the lockdown relate to aspects that are likely to subside when restrictions are lifted (e.g. reopening of schools, meeting with family and friends, enjoying leisure activities). Other negative aspects relate to the fast pace in which academic staff had to switch to online activities, sometimes without adequate workspace, equipment and/or training, leading to overwork. On the other hand, respondents report many substantial advantages of working from home, many wishing that this can continue (at least for part of the time) in the longer term. This is a summary of the advantages respondents have identified:

- No travelling = more control over time + less exhaustion + less expense + better for the environment + spending more time with family

- Healthier – nutritionally better, more physical rest, more exercise

- Staying safe – better protected at home, avoiding traffic hazards

- Gaining extra hours to work

- Slower pace = more time to concentrate; a breathing space

- Greater autonomy to manage time and priorities

- Greater flexibility = ingenuity and novelty, new ways of teaching and supporting students remotely

- Less stress and physical/mental wear-&-tear

- Stripping back work dross – basic priorities reveals a lot of bureaucracy that can be avoided

Who are the respondents?

Exposure to Covid-19

- 7% of respondents (5 out of 68) had severe symptoms of Covid-19 or tested positive or live with someone who did. All are female respondents in their 20s, 30s and 50s. Two of these households had someone at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19.

- 22% of respondents (15 out of 68) had close family members, friends or colleagues who had severe symptoms of Covid-19 or tested positive. All are female respondents in their 30s, 40s and 50s (the majority, 9 respondents).

- 41% of respondents (28 out of 68) live in a household where there is at least one person at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19.

Figure 1. Changes in work-life balance of respondents during Covid-19 lockdown (a) and the selected reasons for identifying positive or negative change (b). ‘Other’ refers to other reasons for improved or worsened work-life balance.

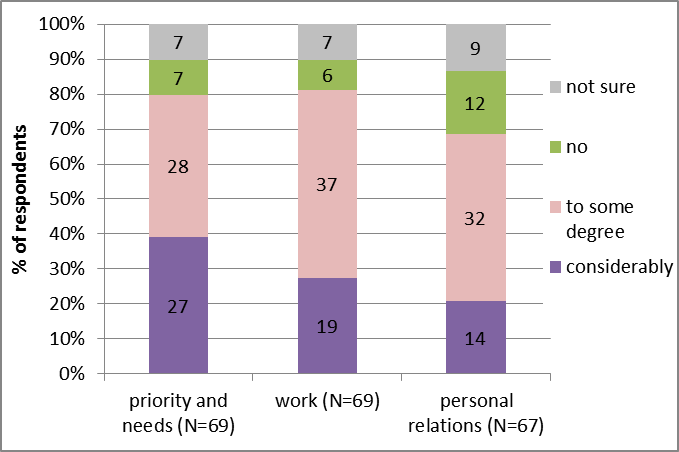

Figure 1. Changes in work-life balance of respondents during Covid-19 lockdown (a) and the selected reasons for identifying positive or negative change (b). ‘Other’ refers to other reasons for improved or worsened work-life balance. Figure 2. The level of impact of selected factors on the work-life balance of respondents during lockdown.

Figure 2. The level of impact of selected factors on the work-life balance of respondents during lockdown. Figure 3. Most cited top two aspects that have affected respondents’ work-life balance (a) positively and (b) negatively (showing categorised responses cited at least five times).

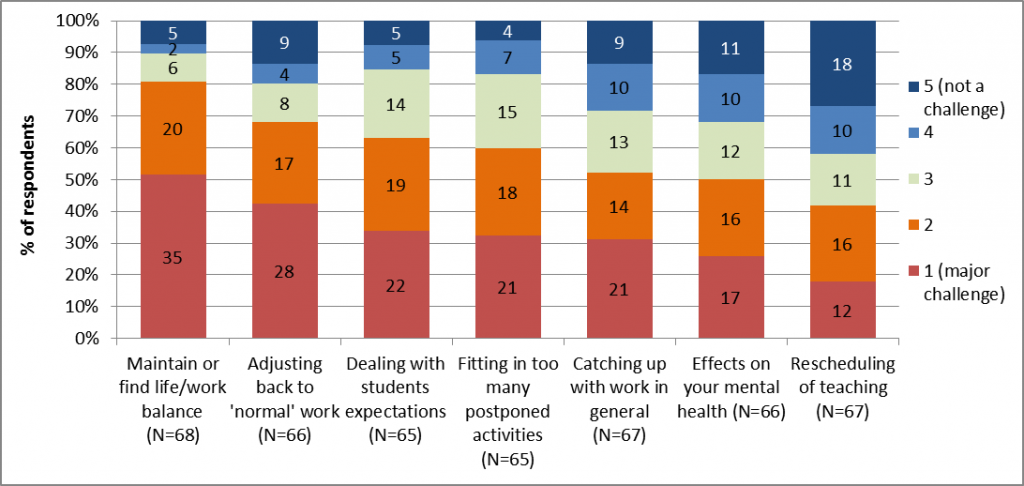

Figure 3. Most cited top two aspects that have affected respondents’ work-life balance (a) positively and (b) negatively (showing categorised responses cited at least five times). Figure 6. Major challenges identified regarding work at the end of lockdown.

Figure 6. Major challenges identified regarding work at the end of lockdown. Figure 7. Perception of long-lasting changes brought by the C-19 outbreak.

Figure 7. Perception of long-lasting changes brought by the C-19 outbreak. A balanced diet is essential for good health. In 2003, the World Health Organisation launched a global campaign to promote fruit and vegetable consumption well-known as the five-a-day mantra. Despite the clear health benefits and prominent media campaigns, still only one in ten children, and less than a third of adults consume this much.

A balanced diet is essential for good health. In 2003, the World Health Organisation launched a global campaign to promote fruit and vegetable consumption well-known as the five-a-day mantra. Despite the clear health benefits and prominent media campaigns, still only one in ten children, and less than a third of adults consume this much.

Expand Your Impact: Collaboration and Networking Workshops for Researchers

Expand Your Impact: Collaboration and Networking Workshops for Researchers Visiting Prof. Sujan Marahatta presenting at BU

Visiting Prof. Sujan Marahatta presenting at BU 3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm

3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching

UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease