The value of providing undergraduate students with experience of conducting first hand, empirical research is widely recognised. As a social anthropologist, I’ve long been interested enabling students to discover and engage in ethnographic research. I’m presently developing a new taught unit in which for our BA Sociology and BA Sociology and Anthropology students will carry out ethnographic projects developed in collaboration with local community organisations. This endeavour necessarily poses challenges. One of them is time. Undergrad students’ learning is divided into units delivered over semesters, but a semester is very short time frame in which to design, carry out and write up an ethnographic project. The other is the nature of the collaboration with the non-academic partner, whether that be an NGO, community group, local government partner etc. How can this collaboration be shaped in a way which is beneficial to both parties?

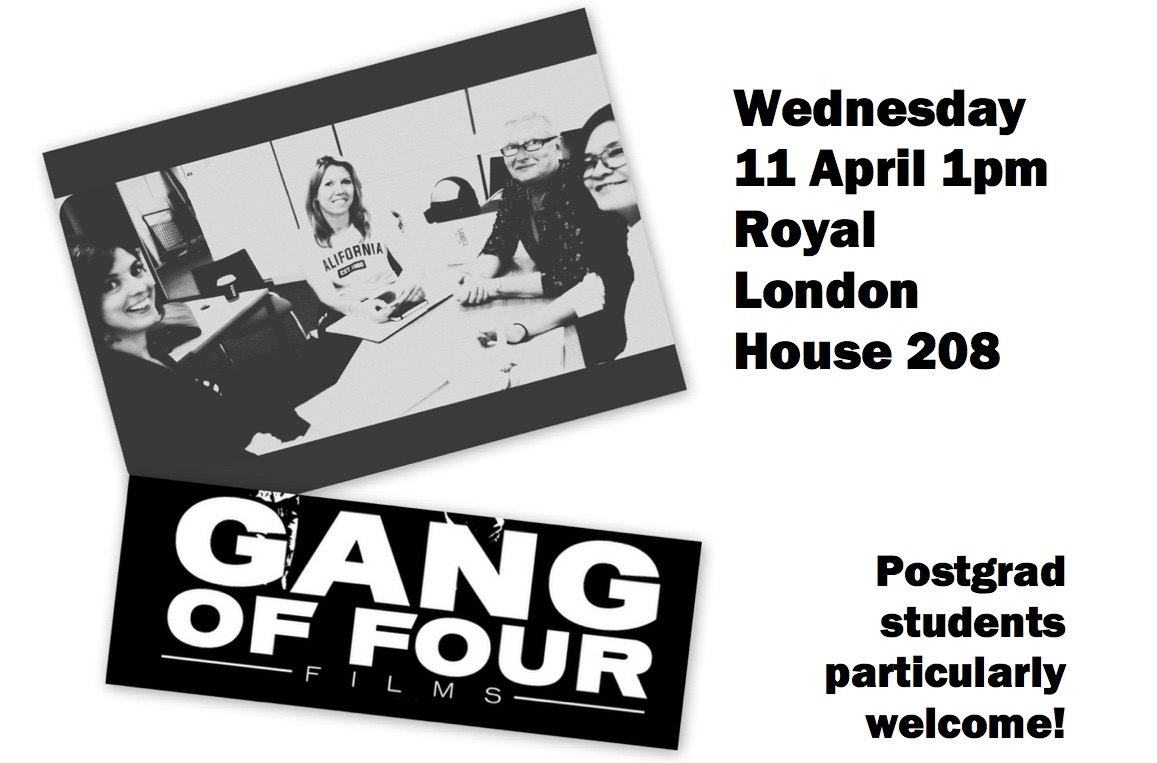

IUPUI students visiting a housing redevelopment scheme in a lower income neighbourhood, Indianapolis, February 2015.

This term I have visited IUPUI (Indiana University Purdue University in Indianapolis), USA. IUPUI is a public university in which dialogue and engagement between faculty and students, on the one hand, and citizens, organisations and businesses, on the other, is a priority for both teaching and research. My visits have provided me with an opportunity to see a diverse range of ways in which this dialogue is promoted and sustained. Here I will summarise some of the strategies I have seen in action at IUPUI which are most pertinent to the kinds of collaborative, community-engaged student ethnographic projects I hope to develop at BU.

1. Investing time

The importance of investing time in developing relationships with local organisations which will have a stake in the research cannot be overstated. Whoever the partner is and whatever the nature of the collaboration, the project is enormously enhanced when both parties make time to talk to each other, arrive at a suitable, realisable aim of the project, and figure out how they are going to achieve it within the fixed timescale. This is of course easy to state and much harder to realise, as it involves all parties investing a very scarce resource, time, into the process. I followed an ethnographic research methods course closely during my visits, a project exploring urban regeneration within a low-income neighbourhood. This made clear the benefits of that early investment of time. Both the academic course leader and management, staff and volunteers at the community development organisation in the local area set aside considerable time in identifying the possibilities and foci of student research projects, long before the teaching proper started. This communication and collaboration also continued throughout the course itself, adjusting to changing and contingent circumstances as the student research projects progressed.

2. Framing the question

Central to the process above is negotiating the research question; what is it that the students will research and why? The question needs to address the interests and priorities of both partners. It must contain the potential for students to formulate their empirical focus and interpret their data in the light of theories and critical questions within their disciplines, and to produce findings which are of some benefit or use to non-academic partners, organisations and citizens. At IUPUI, I found out about series of student projects on urban development issues such as poverty, homelessness, housing, city regeneration strategies, gentrification and food production and consumption, to name some of them. These kinds of topics resulted in findings and interpretations which had both critical value as pieces of academic work and practical value to local people and organisations.

3. Moving teaching to community settings

I closely followed two courses which were taught off-campus in community settings – one in a church / community centre, the other in a women’s correctional facility. The success of any ethnographic project hinges on proximity and familiarity and so establishing this sense of closeness is obviously of enormous value to students. Teaching in a setting within which students will find an immediate mutuality of interest in their engagement with the people and organisations they are going to study helps students think of themselves as ethnographers. It provides the basis for developing relationships, trust, access and cooperation within the community, and for fostering local understanding of what the project is about. This is also a valuable experience that students take with them into their future careers.

4. Finding (new) ways of disseminating the research findings

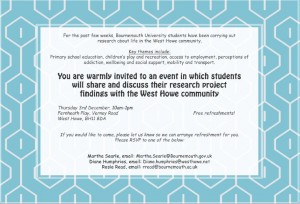

Academics at IUPUI employed many different means of disseminating their students’ research projects and findings, enabling it to reach audiences within but also well beyond the city itself. Students were strongly encouraged and sometimes financially supported to attend national and international conferences. Funding was raised for publishing pamphlets, books and eBooks about their empirical studies and findings. Time was invested in developing impressive academic blogs and websites about their research. I provide a few links to just some of this fantastic work below.

I have gained many insights, ideas and sense of possibilities from my visits to IUPUI, and I’d like to extend my warm thanks to all colleagues and students whom I had the pleasure of meeting. Special thanks to Professor Susan B. Hyatt, whose scholarship inspired my visits and who made the whole thing possible in a practical sense.

Links to some online examples of IUPUI collaborative student research and scholarship:

– The ‘Neighborhood of Saturdays’. Student research project about urban multi-ethnic neighborhood in Indianapolis.

– ‘Eastside Story: Portrait of a Neighborhood on the Suburban Frontier’: Student project exploring historical change and community identities in a suburban area of Indianapolis.

– ‘Urban Heritage? Archaeology and Homelessness in Indianapolis’. A student project using archaeological methods to explore experiences of homelessness.

– ‘Ransom Place’ project: Collaborative project on culture, consumption and race in an African American neighbourhood in Indianapolis: http://www.iupui.edu/~anthpm/ransom.html

– ‘Archaeology and Material Culture’: blog of Professor Paul Mullins.

https://paulmullins.wordpress.com/author/paulmullins/

Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop

Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching

UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives BRIAN upgrade and new look

BRIAN upgrade and new look Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh

Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease