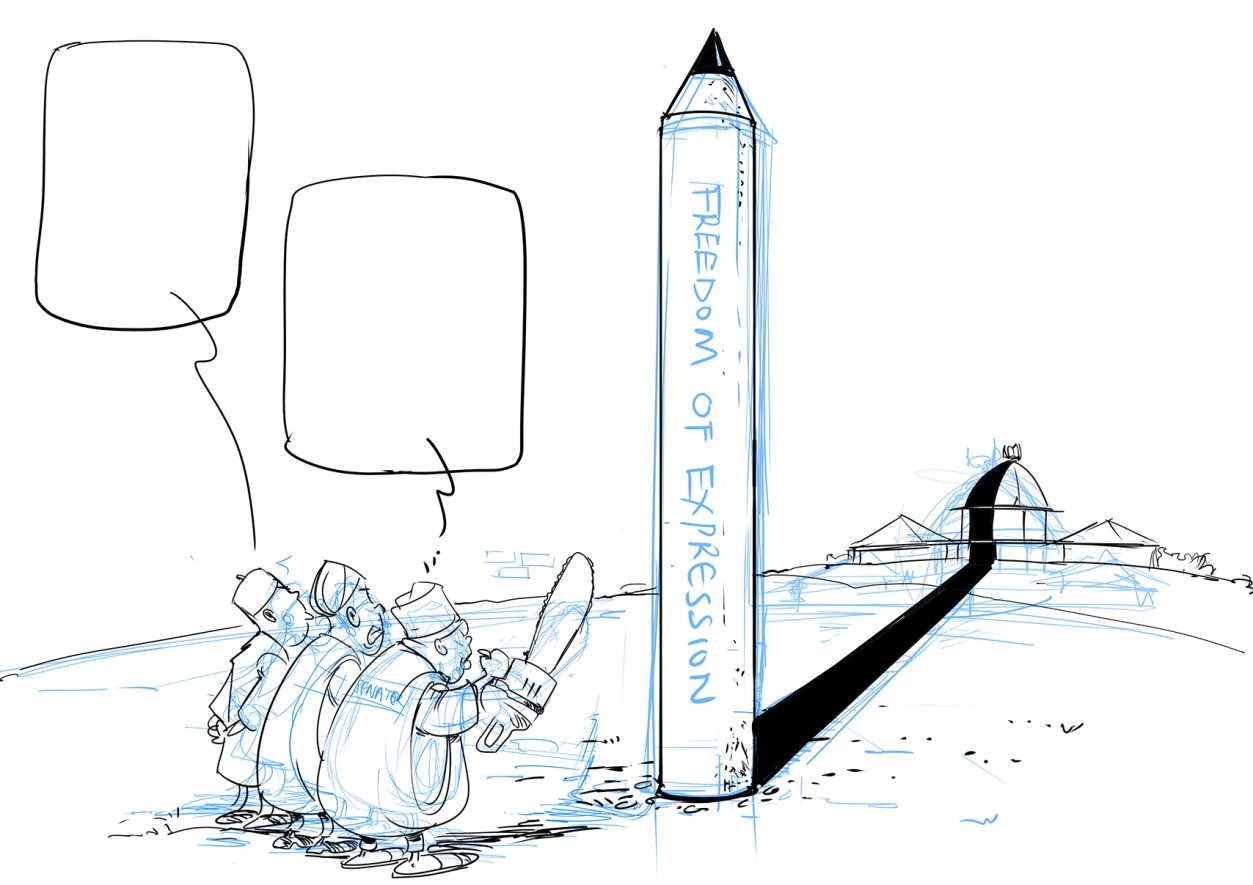

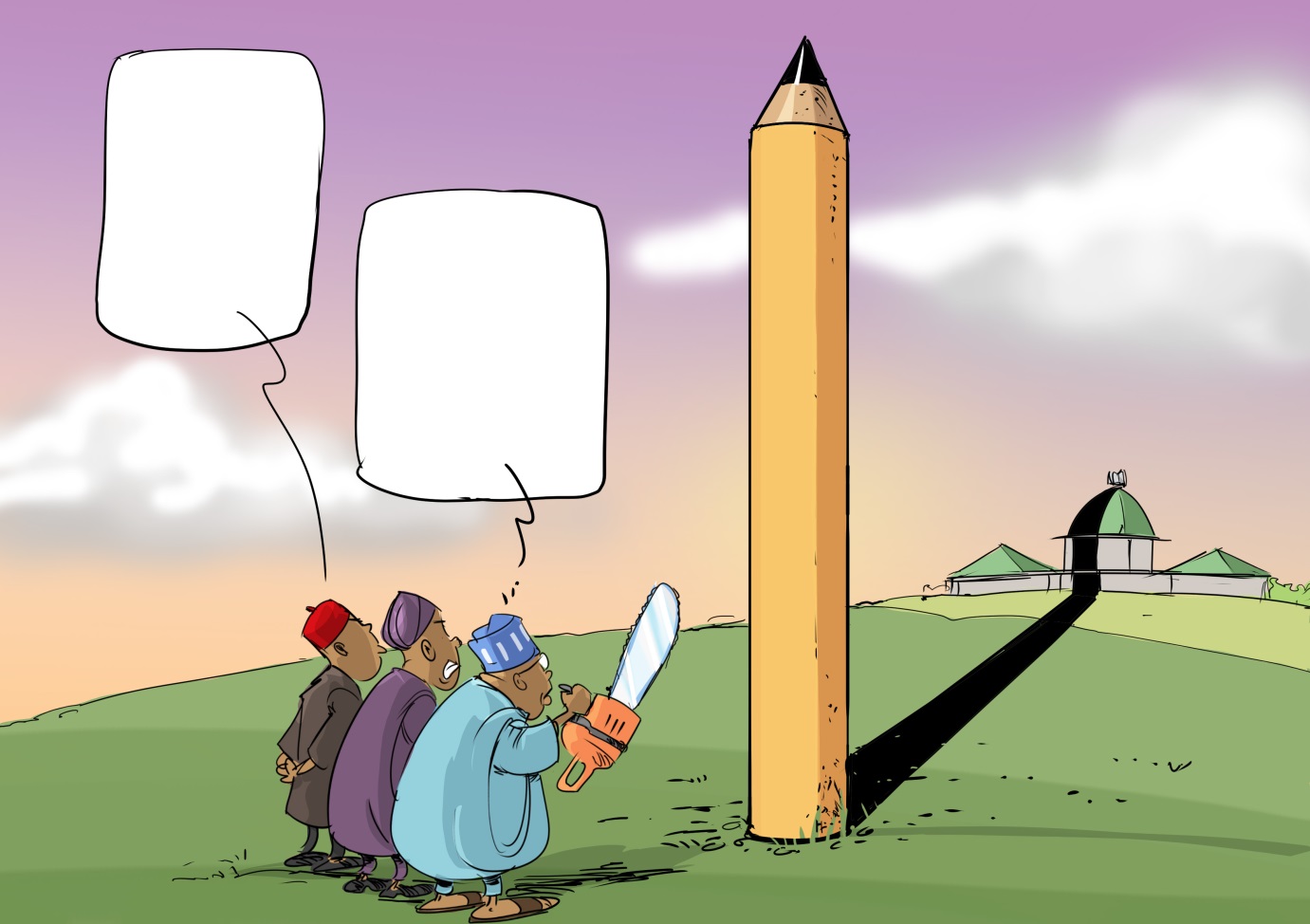

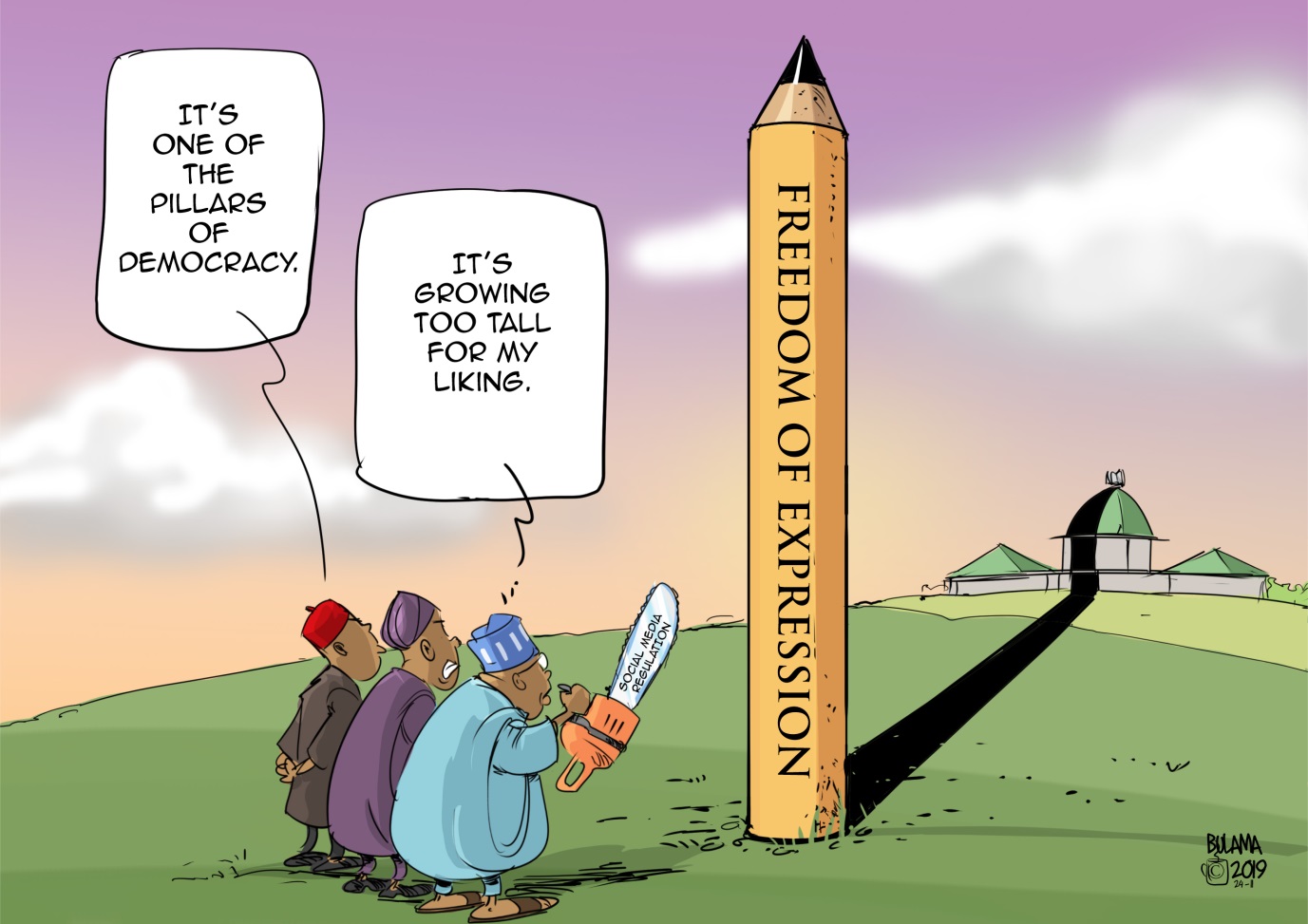

The AHRC research project, ArtoP: The Visual Articulations of Politics in Nigeria sets out to collect and archive visual material that is produced by artists, animators, filmmakers, photographers in Nigeria around and following the elections in February 2019. As part of the project outputs, the research will culminate in a digital archive that will serve two purposes i) to preserve this collection over a period of 10 years and ii) to disseminate parts of the collection with a wider public through a web-based platform. These outputs present a number of challenges that highlight the importance of planning for digital archiving and ensuring its sustainability given the rapidity with which digital traces are created, disseminated and in turn disappear (Ernst, 2013). This post forms part of a longer paper in development that seeks to focus upon changes in archival practice in the arts, especially where contexts of contemporary image making practices tend to be based in the digital and circulate in virtual spaces. Additionally, the variances in technological landscapes across different geographies also present separate sets of challenges that a researcher may face – who has access to this data; which voices are included and excluded; how does one curate for fair access?

Collecting Digital Images

In 2018, the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston) ran an exhibition on ‘Art in the Age of the Internet’, that examined how ‘the internet has radically changed the field of art, especially in its production, distribution, and reception’ (Respini, 2018). This exhibition is connected to a wider ongoing discourse within the arts on digital media (Gere, 2004, 2006) and the impact this is having upon museums and galleries. Therefore it is not surprising to see that in recent years there has been a growing recognition of the urgent need to actively collect and preserve digital art and digital graphics – material which is inherently ephemeral. Archives have been tempted to wait until a top down collections management system is developed. This has resulted in gaps in collections.There is a consensus emerging that researchers and archivists urgently need to take a DIY, active approach to collecting digital content as near to the time of its publication as possible. Unlike physical collections, there is less chance of acquiring large collections of digital content at a later date, long after the material was created. This is because material on digital platforms are fleeting, with people entrusting storage of their digital creations to third-party proprietorial platforms whose commitment to the long term preservation of material is uncertain:

“Digital works increasingly operate within a culture that replaces ownership with access. The idea that anything is accessible anytime online changes the motivation to collect and archive within the personal sphere. Personal cultural material is now embedded in proprietary software and third party platforms where responsibility for its longevity in a fast changing technological environment is ambiguous. Certainly, the ability to capture the online object within the context which makes it meaningful recedes as time passes […] digital collecting is best approached as a process of rapid response.” (CCDP 2018)

One only needs to think of the demise of Myspace, a once-popular social media platform and a medium for sharing artwork and music, which recently lost all content uploaded by users before 2016, to recognise how transient and vulnerable our individual and collective digital heritage is. (Hern 2019)

Capturing Context and Circulation

Another challenge in collecting and archiving digital images and artworks is capturing the contexts and the patterns of circulation which make the images meaningful. Simply saving a digital graphic as an individual image file severs the image from its context. One challenge has been in capturing the interactive web environments in which digital graphics are published, republished and commented upon by users of Web 2.0. The sharing and modification of images online by a variety of actors is increasingly rapid and dynamic. For example, people can change the meaning of an image by reposting it on social media with a different caption, presenting new opportunities for engaged political citizenship and satire (Agbo 2018). This, along with the growing availability of digital editing tools, which are often embedded within the interface of social media platforms themselves, also allow users to easily edit the visual content of images, leaving them ripe for subversion and parody. Social media users quickly respond to each other in a humorous, conversational form, in ways which reframe images, reference earlier posts and trade ‘in-jokes’. In such exchanges users demonstrate their visual literacy and quick textual wit (Dike 2018). As both the content and context of digital images is endlessly mutating, it doesn’t make sense to archive once instance of an image, or even to think in terms of individual images. A recent report by the Collecting and Curating Digital Posters (CCDP) project recommends thinking in terms of “graphic events” rather than discrete images in order to reflect the ongoing social practices in which images are referenced, negotiated and transformed. We should capture many iterations of the same image, the way in which they have migrated, the online environments in which they are encountered, and the ways audiences have interacted and commented on the images. The CCDP project recommends using the open-source tool Web-Recorder, in which collectors ‘record’ a web session, allowing them to capture their experience of browsing a website, trace the circulation of images online and record the ways in which it was possible to interact with digital graphics within native software and social media environments. These ‘sessions’ can be saved and played back by future users of the archive using the open source Web Recorder Player.

There are problems in capturing such phenomenon in retrospect. The rapidly changing appearance and technological environment of social media platforms introduces temporal distortion when searching social media platforms for, say, memes produced in response to a particular political controversy in 2014. We need to capture such phenomena as soon as possible. This requires us to be active and embedded users of the web in order to spot emerging visual trends as they occur.

‘The archival infrastructure in the case of the Internet is only ever temporary, in response to its permanent dynamic rewriting. Ultimate knowledge (the old encyclopedia model) gives way to the principle of permanent rewriting or addition. ‘ (Ernst, 2013:85)

Storage and Access: Open Source Solutions.

‘Our obsession with memory functions as a reaction formation against the accelerating technical processes that our transforming our Lebenswelt (lifeworld) in quite distinct ways. [Memory] represents the attempt to slow down information processing, to resist the dissolution of time in the synchronicity of the archive, to recover a mode of contemplation outside the universe of simulation, and fast-speed information and cable networks, to claim some anchoring space in a world of puzzling and often threatening heterogeneity, non-synchronicity, and information overload’. (Husseyn, 1994)

Any discussion of a digital archive necessitates an active engagement with technological apparatus in order to consider the relationship between a technological environment and the production of (and obsession with) memory (Husseyn 1994). Storage and preservation are key aspects to any discussion on digital archiving, and as digital technologies accelerate their pace of change, paradoxically, so must a digital archive respond to this by mitigating against it.

Storage and preservation

A question we faced in designing the ArtoP project was which software we should use for digital preservation and storage. Digital preservation can be difficult as the file formats we may take for granted now can become obsolescent in future – the software which opens them can disappear, rendering the contents of a file irretrievable. We therefore wanted to ensure that material was packaged in stable file formats, adhered to widely agreed-upon archival standards, and was stored securely. We identified Archivematica as the ideal software for our purposes.

Archivematica is an open source, web-based digital preservation system that is used by a variety of institutions. The fact that the software is open access and free to install and operate actually ensures greater longevity. Proprietary software, tied to the variable fortunes of individual companies, are more liable to disappear than open source projects, which enjoy the support of an active community of users and developers.

Archivematica is not a single piece of software but rather an ecosystem containing a number of tools, components and specifications which run the ‘microservices’ necessary to preserve digital content. For example, one of the microservices performed by Archivematica is called ‘normalisation’. During normalisation the files you upload are converted into preservation-friendly formats, using an active list of stable and accessible file formats compiled and updated by the UK National Archives. This provides some insurance against the rapid cycles of change and obsolescence which characterise the life of file formats.

Archivematica’s core functions are as follows:

- User submits data to Archivematica in the form of Submission Information Packages (SIPs)

- From the SIPs, Archivematica creates Archival Information Packages (AIPs) for the long term preservation of data.

- Archivematica stores (and backs up) AIPs

- Archivematica creates Dissemination Information Packages (DIPs) to export content to populate an archival access system, such as Access to Memory (AtoM), Archive Space, Figleaf etc.

Ensuring Access

As mentioned earlier, another priority of the project was to make a selected range of images from the archive available for public consumption through a public archive hosted on a web-based platform. Increasingly users of archives wish to be able to actively interact with collections and desire wider access (Fossati 2009), challenges which digital access and display offers potential solutions to. For this process we are opting for the web-based access platform Access to Memory (AtoM).

Like Archivematica, AtoM is open source – it is free to use, free to share and free to develop. All documentation is freely available online. This is complemented by a supportive community of users, who communicate and solve problems using a google mailing list, as well as by congregating in person at the UK User Group’s meetings, which are attended by a number of archivists and librarians from prestigious UK universities.

AtoM supports the use of a choice of widely agreed-upon archival standards for describing archival objects. This enables digital images to be presented along with explanatory context, or metadata, crucial to its understanding. Using archival descriptive standards also means there is the potential for us to link the material to larger aggregators of archival holdings, and material on our access page could be discovered by people using archival search portals such as Archives Hub.

Crucially, AtoM is also integrated into Archivematica – the two systems were developed by the same company and are configured to ‘speak’ to one another. Archivematica produces Dissemination Information Packages (DIPs) that can populate AtoM with images, video and metadata.

We also liked how AtoM can be customised according to the diverse needs of different organisations and audiences. We aim to hold workshops in Lagos to ask for feedback from Nigerians as to how they think material should be described and presented to the public, and we will attempt to customise our AtoM page accordingly. Rather than projecting our own assumptions on the material by presenting it in certain ways, we are eager to have this determined by local knowledge and needs, as well as local technological landscapes (see below). Moreover, Atom features multi-lingual support, with the potential to add translations, making the material relevant to different audiences. Our aspiration is for the public side of the archive to be a resource for Nigerian citizens, artists and researchers.

We are inspired by the wide range of institutions that have used and customised AtoM in creative and innovative ways to present visual context, ranging from the Glasgow School of Arts to The Chinese Canadian Artefacts Project. We are currently exploring and brainstorming ways of customising AtoM.

Local technological landscapes

One of the considerations we need to bear in mind when customising our web-based access system is the local technological landscapes used by our primary audience: Nigerians. Digital technology has been harnessed by Nigerian artists and citizens to make political critiques, and has afforded Nigerians with new strategic opportunities to produce and circulate indigenous knowledge within global flows of information. Many Nigerians primarily access the internet using smartphones. Thus we need to consider designing our web-based access system in ways which are suitable for mobile browsers. Additionally, to align with the UN Sustainability Development Goals, we are keen to ensure that access to this archive for educational purposes is designed for Nigerian users and their specific technological landscape, in order for it to have the greatest impact in Nigeria (and other African countries). Therefore, we also need to ensure that our website is accessible to users whose bandwidth may be limited and for whom mobile data is a significant expense. This might involve customising file normalisation in Archivematica in order to produce lower resolution image and video files for access purposes, which will load much quicker for users with slower internet connections or limited data.

We are still in a development phase and will be researching the local technological landscape in Nigeria further, as well as soliciting advice from Nigerians as to the form our access system should take.

In the meantime we wanted to take this opportunity to share our experiences, and hope to forge new relations with academics that may also be considering approaches to digital archiving. We hope to see our research extending to considering a range of formats and elements that may contribute to the generation of digital still or moving images and that sit within a more complex pipelines such as those in CGI for example, and the implications of this to archival practices.

Therefore, any feedback from readers of this blogpost is of course welcome – please contact

PI Dr. Paula Callus – pcallus@bournemouth.ac.uk

CoI Dr. Charles Gore – cg2@soas.ac.uk

RA Dr. Malcolm Corrigall – mcorrigall@bournemouth.ac.uk

Bibliography

Agbo, George Emeka, (2018). “The Struggle Complex: Facebook, Visual Critique and the tussle for Political Power in Nigeria” Cariers D’étude Africaines 230, pp.469-89.

CCDP, (2018). Collecting and Curating Digital Posters Handbook, https://ccdgp.co.uk/index.html.

Dike, Deborah N. (2018), “Countering Political Narratives through Nairaland Meme Pictures” Cahiers D’étude Africaines 230: pp.493–512

Ernst, W. (2013), Digital Memory and the Archive, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Gere, C. (2006), Art, Time and Technology, Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Fossati, G. (2009), From Grain to Pixel, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Hern, A. (2019) “Myspace loses all content uploaded before 2016”, The Guardian, March 18. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/mar/18/myspace-loses-all-content-uploaded-before-2016

Haskins, E. (2007), ‘Between Archive and Participation: Public Memory in a Digital Age’, in Rhetoric Society Quarterly, Vol.37, pp. 401-422.

Huyssen A. (1994), Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia, London p.253.

Prof Marahatta promoting BU-Nepal collaboration

Prof Marahatta promoting BU-Nepal collaboration 3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm

3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March

Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward?

Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward? ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease