How can we do research that engages with communities in a genuinely collaborative way? What kind of research produces findings which address critical questions about the structural issues and problems faced by communities, but which are also of practical and transformative benefit to them? If these two objectives pull researchers in different directions, what kind of balance can be struck between them?

These are questions I have been pondering during two visits this semester to IUPUI (Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis), in Indianapolis, USA. This is a university which places strong emphasis on the importance of community collaboration and engagement in scholarship and education. During two visits, I have particularly followed the community engaged work of Professor Susan Brin Hyatt.

I have known Professor Hyatt since June 2013, when she came to Bournemouth University to give a research seminar presentation about urban ethnographic research projects she and her students had undertaken in Indianapolis and Philadelphia (e.g., Hyatt et al 2012, Hyatt et al 2009. See also Hyatt 2001). During her visit we talked a lot about our common scholarly interests and discovered that we had a shared interest in the British Community Development Projects (CDPs) of the 1970s. The CDPs provide a very interesting example of the politics of using academic knowledge to bring about social change – or what we now call (societal) impact.

Meadow Well playground, 1976. Photography courtesy of Ken Grint. Available at IUPUI Digital Archive: http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/CDP/id/3685/rec/120

Initiated in 1969, the CDPs were a major social policy initiative, by the standards of then and now. There were twelve CDPs across the UK – mostly based in urban, industrial areas affected by economic decline, job loss and poverty. CDPs were set up with the aim of using community action to tackle various social problems associated with poverty and develop more integrated forms of service provision which responded to the local population’s needs. Each of the twelve CDPs incorporated a research team based in a university, and an action team based in the community, accountable to a local steering group. The idea was that social science knowledge and methods should both inform and support the development of local projects. The CDPs had an estimated budget of £5 million – a lot of money in those days. Most of the funding came from central government, but local CDPs operated with a high level of autonomy.

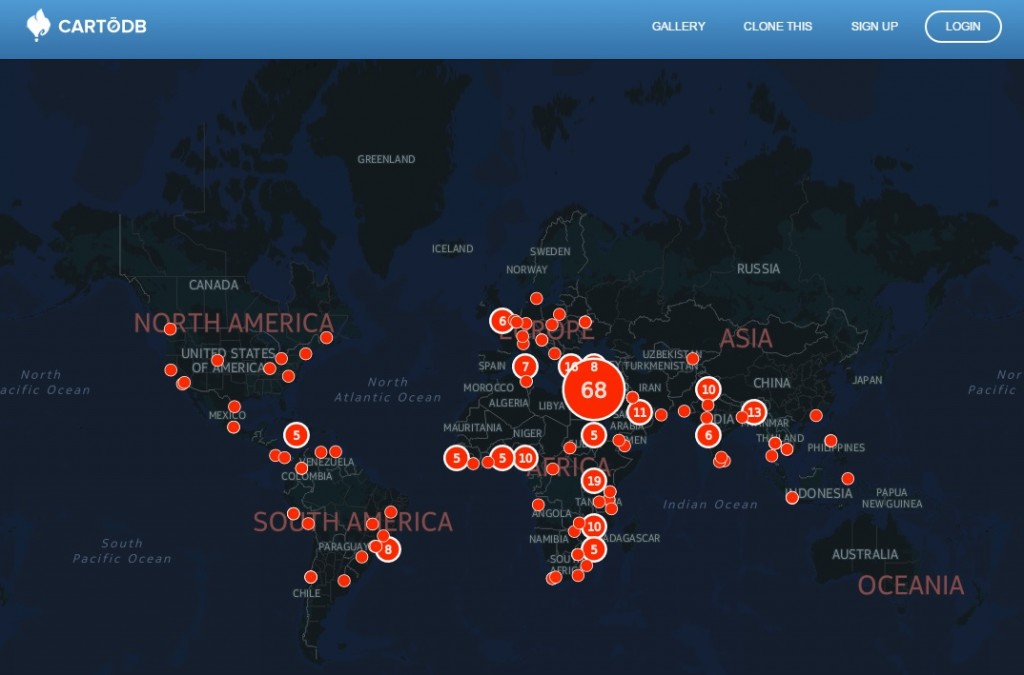

It is interesting to reflect on the CDPs from today’s vantage point. This was the creation of an ambitious infrastructure, across 12 regions, linking universities and academic researchers directly with community workers and activists in poor areas, with the explicit aim of enabling social science to inform social transformation. It is hard to imagine such a wide-ranging initiative emerging now, backed up by an equivalent budget from central government departments, in spite of widespread current concerns about growing use of food banks, zero hours contracts, high levels of in-work and child poverty and obscene income and housing inequalities; the kinds of problems which, some argue, are far more endemic now in the UK than they were in the 1970s.

Yet the CDP story is one in which two conflicting explanations of the causes of poverty unfolded (Loney 1983). The politicians and civil servants who set up the CDPs assumed a social pathology definition. They understood poverty to result essentially from the actions and beliefs of the poor themselves. From this viewpoint, what was needed was better, more joined up local services to help the poor to improve their skills and lifestyles, and become better adapted to the new economic realities of deindustrialisation. By contrast, those who worked for the CDPs quickly abandoned this definition of poverty in favour of a more structural perspective, attending to how social and economic policies reflected within corporate and government decision-making directly and indirectly gave rise to poverty and related social problems. In effect the CDP researchers, workers and activists refused to ‘localize’ the cause of the issues they tried to tackle. Their structural perspective informed how community action and research was used to engage, inform and mobilise local populations, and transform people’s lives for the better. This brought about many positive changes in areas in which CDPs were active and left some important legacies. However, this kind of impact was not what the government had in mind. CDPs were eventually wound down in the late 1970s, by which time politicians and senior government officials had mostly switched off from considering the implications of their findings for social policy at a wider level.

Although this was forty years ago, the CDPs have a strong contemporary resonance. Many of the problems tackled by the CDPs (poverty, insecure low paid work, unemployment) continue today, as do debates over how to deal with them. The activism and scholarship produced by the CDPs illustrates vividly how attempts to bring about positive change (to make an impact) in poor communities necessarily depends upon definitions of poverty which are always, inescapably political, whether or not they are recognised as such. As part of her research on British CDPs, Prof Hyatt and her colleagues at IUPUI have created a unique and extensive digital archive of many CDP reports, publications and photographs. This is an excellent resource for both teaching and research and I would like to recommend it to all colleagues interested in the issues discussed here.

References

Hyatt, SB., Linder, BJ., and Baurley, M. eds. 2012. The Neighborhood of Saturdays. Memories of a Multi-Ethnic Community on Indianapolis’ South Side. Indianapolis: Dog Ear Publishing.

Hyatt, SB., Branstrator, DW., Baurley, M., Dagon M., and Yarian, S. eds. 2009. Eastside Story. Portrait of a Neighborhood on the Suburban Frontier. Indianapolis: Department of Anthropology IUPUI, Neighborhood Alliance Press.

Hyatt, Susan B., 2001. From Citizen to Volunteer. Neoliberal Governance and the Erasure of Poverty. In Judith Goode and Jeff Maskovsky, eds. The New Poverty Studies. The Ethnography of Power, Politics and Impoverished People in the United States. New York: New York University Press.

Loney, Martin 1983. Community Against Government. The British Community Development Project 1968-78. London: Heinemann

BU students in the Humanities and Law Department, Shahidah Miah (3rd year Law student), Alex Carey (2nd year History student) and Josh Pitt (3rd year Politics student) won the Distinguished Delegation Award at the BISA Model NATO. The event took place at the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office on Friday, March 3rd, and was organized by the British International Studies Association in partnership with FCDO.

BU students in the Humanities and Law Department, Shahidah Miah (3rd year Law student), Alex Carey (2nd year History student) and Josh Pitt (3rd year Politics student) won the Distinguished Delegation Award at the BISA Model NATO. The event took place at the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office on Friday, March 3rd, and was organized by the British International Studies Association in partnership with FCDO.

Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop

Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching

UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives BRIAN upgrade and new look

BRIAN upgrade and new look Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh

Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease