Professor Rick Stafford and Zach Boakes write for The Conversation about their research exploring whether artificial reefs in the tropics can function in the same way as natural ones…

Artificial coral reefs showing early signs they can mimic real reefs killed by climate change – new research

Rick Stafford, Bournemouth University and Zach Boakes, Bournemouth University

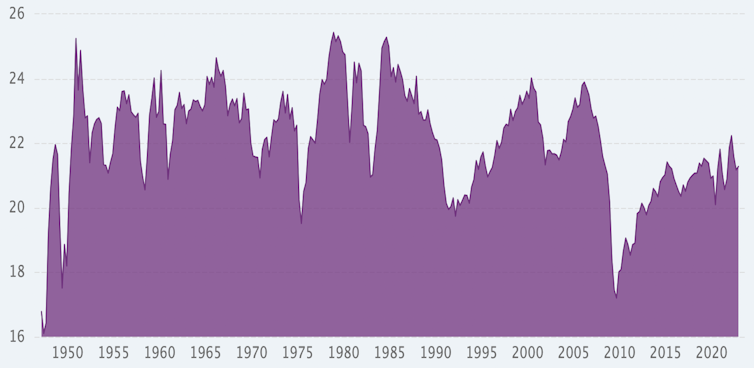

Earth’s average temperature in September 2023 was 1.75°C above its pre-industrial baseline, breaching (if only temporarily) the 1.5°C threshold at which world leaders agreed to try and limit long-term warming.

Persistent warming at this level will make it difficult for the ocean’s coral reefs to survive. The same goes for those communities who rely on the reefs for food, to protect their coastline from storms and for other sources of income, such as tourism. Recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessments have predicted that even if global heating is kept within the most optimistic scenarios, up to two-thirds of all coral reefs could deteriorate over the next few decades.

It will not be possible to restore all the reefs lost to climate change. But we are scientists who study how to preserve these habitats, and we hope that artificial structures (made from concrete or other hard materials) could replicate the complex forms of natural reefs and retain some of the benefits they provide.

We know artificial reefs can attract fish and host high levels of biodiversity – often similar to natural reefs. This is partly due to them providing a hard surface for invertebrates like sponges and corals to grow on. Artificial reefs also offer a complex habitat of crevices, tunnels and other hiding places for species that move around a lot, such as fish, crabs and octopus.

Until now though, scientists were unsure if artificial reefs attracted wildlife which would otherwise live on nearby coral reefs or whether they helped support entirely new communities, enlarging existing populations. This is important, because if natural reefs do die, these artificial structures must be self-sustaining to continue benefiting species, including our own.

BankZa/Shutterstock

Our recent study is the first to examine whether artificial reefs in the tropics can function in the same way as their naturally formed counterparts. The answer is: not yet, but these concrete structures are beginning to mimic some of the key functions of coral reefs – and they should get better at it over time.

Follow the nutrients

Coral reefs support lots of different species in high numbers despite growing in tropical waters low in nutrients (chemicals such as nitrates and phosphates which boost plant growth). This puzzled naturalist Charles Darwin, and it became known as Darwin’s Paradox. We now know reefs achieve this by circulating nutrients extremely rapidly through the invertebrates, corals and fish that live on them.

In a healthy coral reef system, nutrients from dead animals and faeces are rapidly consumed by animals living on the reef, such as small fish or invertebrates, and these small animals are frequently eaten by larger animals. This ensures these nutrients cannot accumulate and so they remain at low levels, preventing algae from overgrowing and smothering the reef.

If artificial reefs perform a similar function to natural reefs then we would expect them to rapidly process nutrients entering the system and keep overall nutrient levels low too. This would indicate they are also highly productive ecosystems, similarly capable of supporting diverse and abundant wildlife even if many natural reefs die.

We tried to make an accurate comparison of natural and artificial reefs by comparing nutrient levels and how they are stored between the two.

From concrete to corals

Our study was conducted in north Bali, Indonesia. A local non-profit, North Bali Reef Conservation, which Zach co-founded, has been making artificial reefs for the last six years with the help of international volunteers and local fishers who use their boats to drop them offshore.

While over 15,000 reefs have been deployed so far, they only cover around 2 hectares – roughly the size of two football pitches.

But these structures are beginning to show signs of functioning like coral reef communities. In water we extracted from just under the sand near the artificial reefs we found high levels of phosphates – evidence of a large number of fish excreting. And in water samples from above the sediment, levels of all the nutrients we measured were low and similar to those recorded on natural reefs, indicating the artificial reef was rapidly recycling these nutrients.

However, the sediment around the concrete structures we tested appeared to be storing less carbon than that surrounding the natural reefs. We think the difference may be related to the relative abundance of invertebrate species such as hydroids (plant-like relatives of corals which feed by sifting detritus from seawater). These were common on the natural reefs we studied, but were only found in small, but increasing numbers on the artificial reefs. We think, as more of these species colonise the concrete over time, the reefs will function even more like their natural counterparts.

The study offers some hope that over time, artificial reefs can mimic more of the processes maintained by natural reefs. Our findings are an early indication that artificial reefs may be able to support local communities affected by reefs lost to climate change.

The climate threat to coral reefs will not be solved by artificial reefs. Only rapidly eliminating emissions of greenhouse gases can preserve a future for these ecosystems. But our research indicates that, where reefs have already been lost, through pollution, destructive fishing or coastal development, it may be possible to restore some of the lost benefits with artificial structures.

Our study suggests it can take up to five years for artificial reefs to begin functioning like coral reefs, so these recovery programmes must begin right away.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Rick Stafford, Professor of Marine Biology and Conservation, Bournemouth University and Zach Boakes, PhD Candidate in Conservation, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

BU’s performance in the third KEF demonstrates several areas of strength, including our research partnerships, working with business, and local growth and regeneration.

BU’s performance in the third KEF demonstrates several areas of strength, including our research partnerships, working with business, and local growth and regeneration.

This week we submitted

This week we submitted

Upcoming opportunities for PGRs – collaborate externally

Upcoming opportunities for PGRs – collaborate externally BU involved in new MRF dissemination grant

BU involved in new MRF dissemination grant New COVID-19 publication

New COVID-19 publication Conversation article: London Marathon – how visually impaired people run

Conversation article: London Marathon – how visually impaired people run MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2024

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2024 Horizon Europe News – December 2023

Horizon Europe News – December 2023