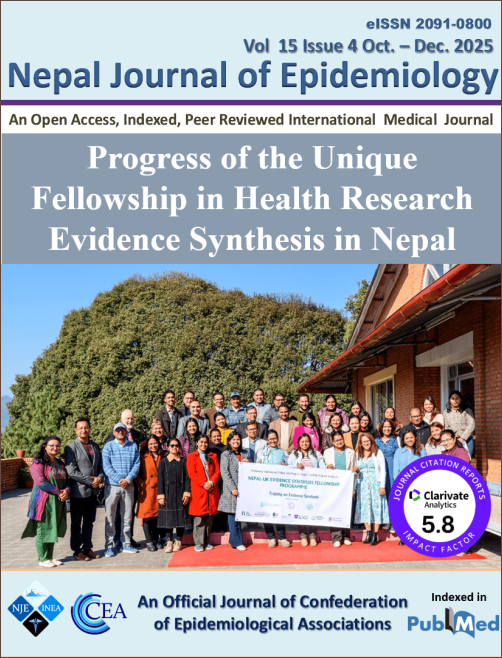

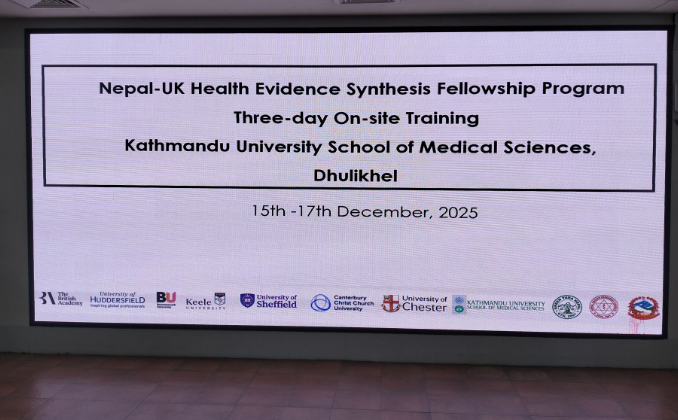

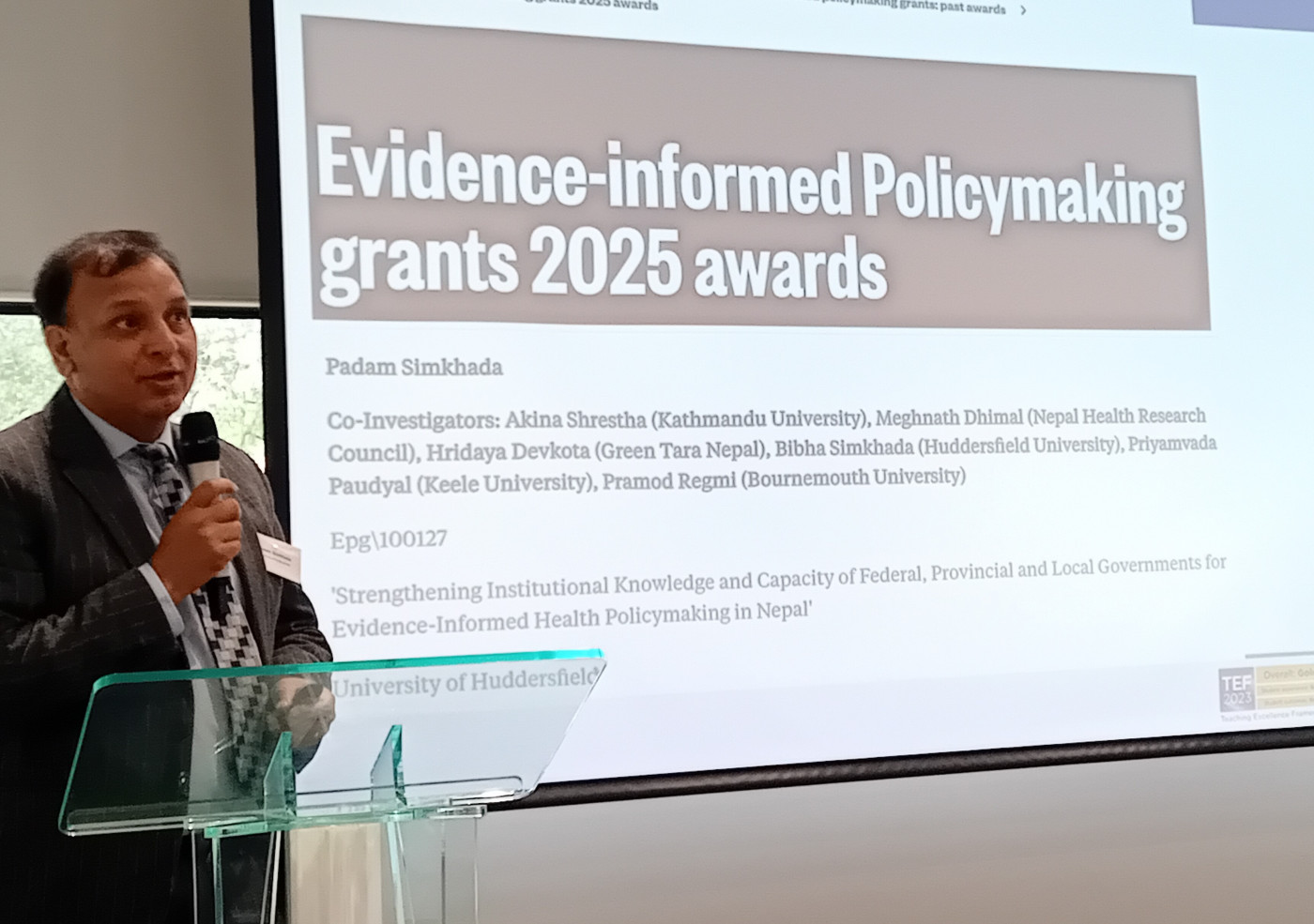

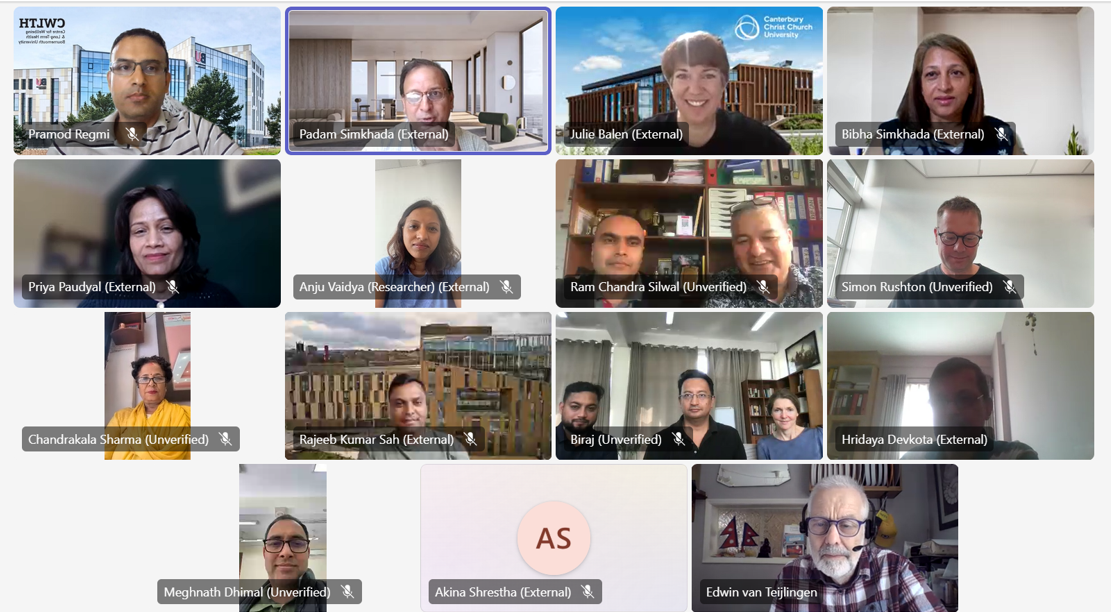

Happy New Year and we hope it will be prosperous and healthy.  On the last day of 2025 the Nepal Journal of Epidemiology published our editorial ‘Progress of the Unique Fellowship in Health Research Evidence Synthesis in Nepal‘ [1]. Co-authors of this editorial include Faculty of Health & Social Sciences Visiting Faculty: Prof. Padam Simkhada and Dr. Bibha Simkhada who are both grant holders on the British Academy grant which also includes BU’s Dr. Pramod Regmi. The journal editor added a photo of our recent three-day event on research capacity building in Dhulikhel (Nepal) to the cover of the December issue.

On the last day of 2025 the Nepal Journal of Epidemiology published our editorial ‘Progress of the Unique Fellowship in Health Research Evidence Synthesis in Nepal‘ [1]. Co-authors of this editorial include Faculty of Health & Social Sciences Visiting Faculty: Prof. Padam Simkhada and Dr. Bibha Simkhada who are both grant holders on the British Academy grant which also includes BU’s Dr. Pramod Regmi. The journal editor added a photo of our recent three-day event on research capacity building in Dhulikhel (Nepal) to the cover of the December issue. Nepalese researchers, academics, policymakers and practitioners are undertaking a unique Fellowship in evidence synthesis and evidence-based policy making. This Fellowship is part of a larger project called ‘Evidence Informed Health Policy Making in Nepal (EHPN)’, funded by the British Academy. After our training event Dr. Regmi had the opportunity to present our (2022) textbook Academic Writing and Publishing in Health and Social Sciences to His Excellency Mr. Madhav Chaulagain, Nepal’s newly appointed Minister of Forest & Environment.

Nepalese researchers, academics, policymakers and practitioners are undertaking a unique Fellowship in evidence synthesis and evidence-based policy making. This Fellowship is part of a larger project called ‘Evidence Informed Health Policy Making in Nepal (EHPN)’, funded by the British Academy. After our training event Dr. Regmi had the opportunity to present our (2022) textbook Academic Writing and Publishing in Health and Social Sciences to His Excellency Mr. Madhav Chaulagain, Nepal’s newly appointed Minister of Forest & Environment.

Evidence-informed policy making developed out of the earlier idea of ‘evidence-based policy making’. The central idea behind evidence-based policy making was that it should be largely (or even solely) guided by evidence. Evidence-informed policy making adds that policies should not just be evidence-based they should also be feasible, appropriate for their context and aligned with stakeholders’ values and therefore one would expect meaningful input from these stakeholders. This is the second editorial highlighting our research capacity-building work in Nepal. The first editorial ‘Strengthening Evidence Synthesis for Health Policymaking in Nepal: A New Fellowship Initiative’ appeared in an earlier edition of the Nepal Journal of Epidemiology [2].

Prof. Edwin van Teijlingen

Centre for Midwifery & Women’s Health

References:

- Vaidya, A., Simkhada, P., Silwal, R. C., Paudyal, P., Dhimal, M., Simkhada, B., van Teijlingen, E. (2025). Progress of the Unique Fellowship in Health Research Evidence Synthesis in Nepal. Nepal Journal of Epidemiology, 15(4), 1397–1398.

- Simkhada, P., Vaidya, A., Regmi, P. P., Paudyal, P., van Teijlingen, E., Dhimal, M., Shrestha, A., Koirala, B., Simkhada, B. (2025). Strengthening Evidence Synthesis for Health Policymaking in Nepal: A New Fellowship Initiative. Nepal Journal of Epidemiology, 15(2), 1379–1380.

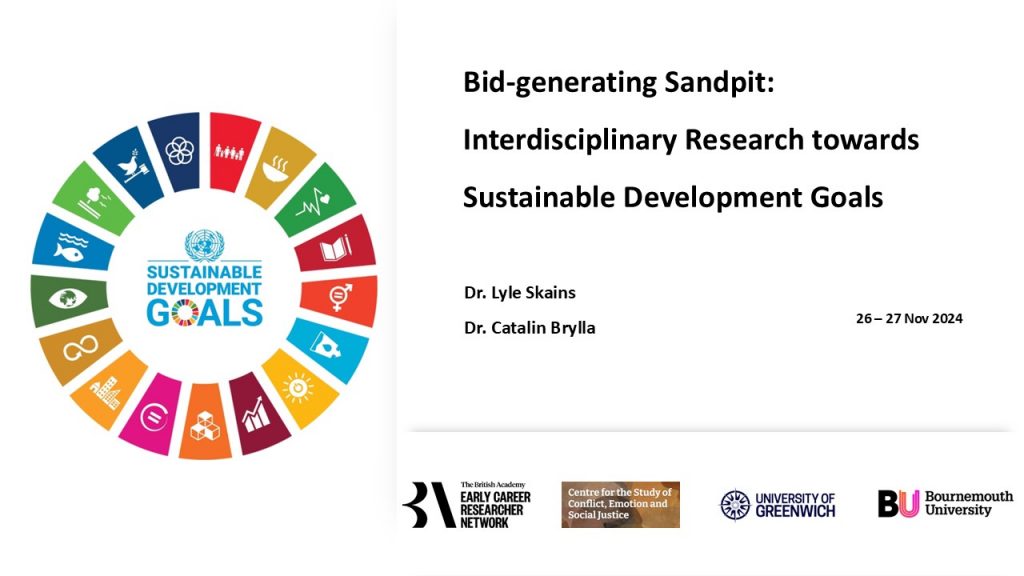

30 early career academics from ten London universities came together on the 26-27 November at Greenwich University for a two-day interdisciplinary sandpit funded by

30 early career academics from ten London universities came together on the 26-27 November at Greenwich University for a two-day interdisciplinary sandpit funded by  The participants specialised in a variety of disciplines such as psychology, anthropology, policy studies, performance, media, tourism, environmental sciences, architecture and law. They brought their interests in a sustainable world and society (as represented by the

The participants specialised in a variety of disciplines such as psychology, anthropology, policy studies, performance, media, tourism, environmental sciences, architecture and law. They brought their interests in a sustainable world and society (as represented by the  experts provided mentorship and feedback on the projects as they developed toward funding proposals. Two sandpit follow-up sessions will also aid the participants in developing their funding proposals.

experts provided mentorship and feedback on the projects as they developed toward funding proposals. Two sandpit follow-up sessions will also aid the participants in developing their funding proposals.

British Academy has launched their Global Professorships

British Academy has launched their Global Professorships

The British Academy is running a project on the SHAPE of research careers, specifically looking at the identity, activity, and mobility of SHAPE postdoctoral researchers, from early career to mid- and late career. We would like to invite anyone who identifies as an early-career social sciences, humanities, or arts researcher to participate in the final workshop, which will be taking place on 1 February 10am to 1pm on Zoom. As a participant in our online workshops, you would also be invited to attend the March conference, with an opportunity to help develop policy options to better support researchers and research, and to network with SHAPE researchers from across UK higher education and other sectors.

The British Academy is running a project on the SHAPE of research careers, specifically looking at the identity, activity, and mobility of SHAPE postdoctoral researchers, from early career to mid- and late career. We would like to invite anyone who identifies as an early-career social sciences, humanities, or arts researcher to participate in the final workshop, which will be taking place on 1 February 10am to 1pm on Zoom. As a participant in our online workshops, you would also be invited to attend the March conference, with an opportunity to help develop policy options to better support researchers and research, and to network with SHAPE researchers from across UK higher education and other sectors.

British Academy Small Grants Workshop aimed at all staff with Research Council bids in development.

British Academy Small Grants Workshop aimed at all staff with Research Council bids in development.

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives BRIAN upgrade and new look

BRIAN upgrade and new look Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh

Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh Exploring Embodied Research: Body Map Storytelling Workshop & Research Seminar

Exploring Embodied Research: Body Map Storytelling Workshop & Research Seminar Marking a Milestone: The Swash Channel Wreck Book Launch

Marking a Milestone: The Swash Channel Wreck Book Launch ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease