Last month we (Ashencaen Crabtree, Ann Hemingway and I) started a survey to collate data from the Women’s Academic Network on the impact of C-19 lockdown, initially targeting BU women academics, and then opening the survey to the wider academic community. We aim to identify lessons learned that can inform what staff and universities can do to reduce the impact of these abrupt changes on our work-life balance, particularly focusing on people who have been most affected. We have received 157 responses to date, 70 we could identify as being from BU staff (63 from female colleagues). The answers are providing a wealth of quantitative and qualitative data and we have just starting the analysis. However, we know how important and timely the findings are and so we have decided to disseminate our initial results in a series of blogs.

If you have not yet contributed to this survey, you are kindly invited to do so here: https://bournemouth.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/impact-of-lockdown-on-academics, and please do share with your networks. If you want us to be able to identify that you are BU staff, you will need to provide this information in one of the open questions.

This Part 1 presents (crude) initial analysis (graphs mainly) focusing solely on the 70 responses from BU staff. We hope this will give you a timely glimpse of how recent changes have affected BU academics. Every day next week we will post a blog with further insights on each aspect covered in the graphs below and others we are yet to analyse, including the key coping mechanisms staff have used during lockdown and the changes respondents think could help improve work-life balance if they remain an option in the longer-term.

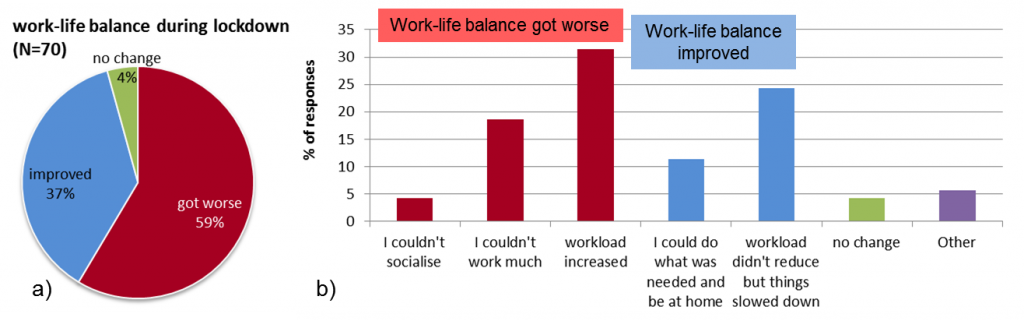

Work-life balance during lockdown got worse for 59% of respondents and improved for 37% (Figure 1). Blog Part 2 will discuss differences across age groups, faculties and career levels.

Figure 1. Changes in work-life balance of respondents during Covid-19 lockdown (a) and the selected reasons for identifying positive or negative change (b). ‘Other’ refers to other reasons for improved or worsened work-life balance.

Figure 1. Changes in work-life balance of respondents during Covid-19 lockdown (a) and the selected reasons for identifying positive or negative change (b). ‘Other’ refers to other reasons for improved or worsened work-life balance.

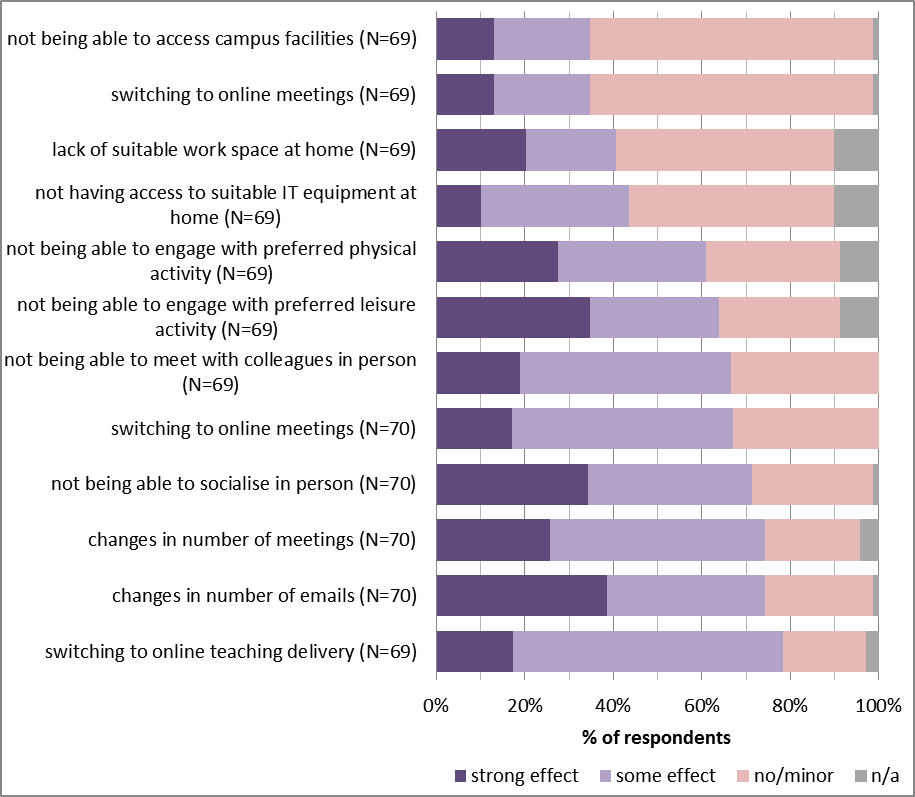

Some factors have impacted the work-life balance of more than 70% of respondents (switching to online teaching, changes in the number of emails, changes in the number of meetings and not being able to socialise in person), while others were considered to have minor/no impact by most respondents (not being able to access campus facilities, switching to online meetings, lack of suitable work space at home and not having access to suitable IT equipment at home) (Figure 2). Some of these factors had a positive effect on the work-life balance of most respondents, while others affected a higher number of staff negatively than positively (see next week’s blogs for more details).

Figure 2. The level of impact of selected factors on the work-life balance of respondents during lockdown.

Figure 2. The level of impact of selected factors on the work-life balance of respondents during lockdown.

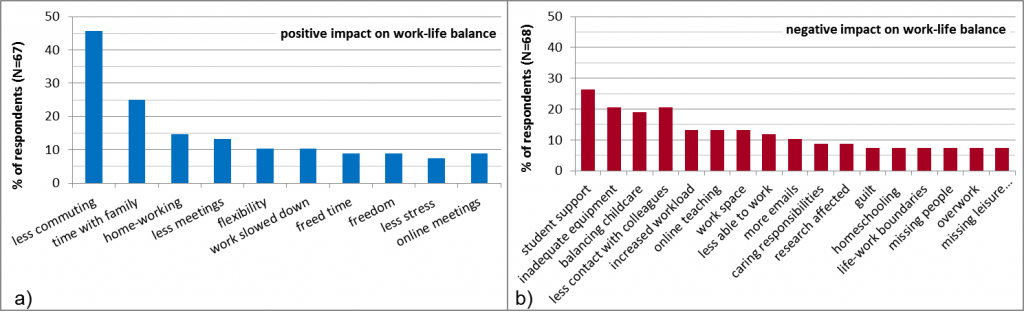

In an open question, less time commuting or travelling for work (46% of respondents) and student support requests (27%) were the most cited factors affecting respondents’ work-life balance positively and negative, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Most cited top two aspects that have affected respondents’ work-life balance (a) positively and (b) negatively (showing categorised responses cited at least five times).

Figure 3. Most cited top two aspects that have affected respondents’ work-life balance (a) positively and (b) negatively (showing categorised responses cited at least five times).

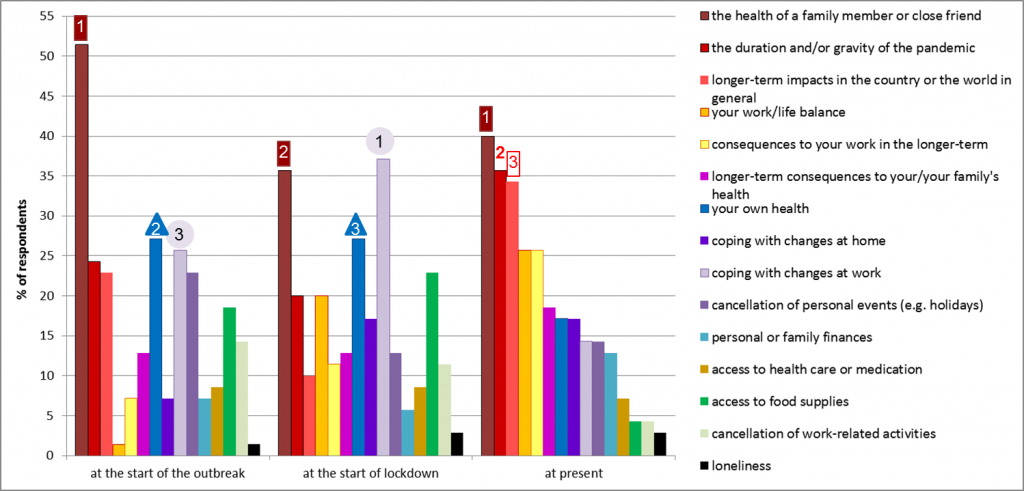

Respondents’ main concerns have changed through time: longer-term impacts in the country or the world in general and work-life balance have become more of a concern at present, while the health of a family member or close friend have always remained within the top three (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Respondents’ main concerns at the start of the outbreak, at the start of the lockdown and at present.

Figure 4. Respondents’ main concerns at the start of the outbreak, at the start of the lockdown and at present.

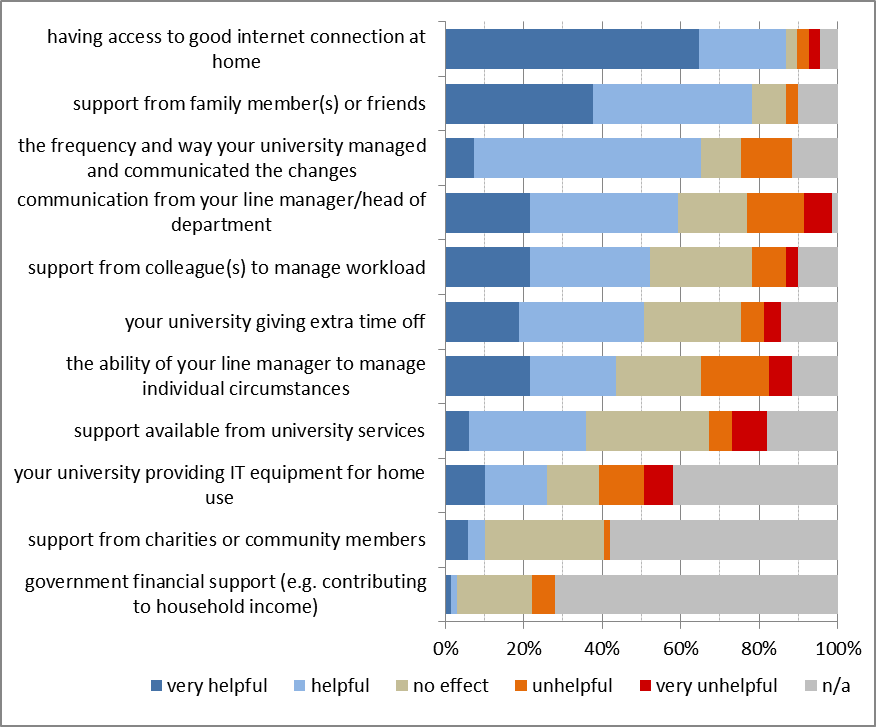

Figure 5 highlights the type of support that was considered to be helpful and the ones that need to be improved to help a larger number of staff (e.g. provision of IT equipment, which BU is currently addressing and support from line managers). Look for the next blogs for further insights on these aspects and suggestions from staff of other support they would welcome from the university.

Figure 5. Respondents indication of how helpful were these particular types of support available to them.

Figure 5. Respondents indication of how helpful were these particular types of support available to them.

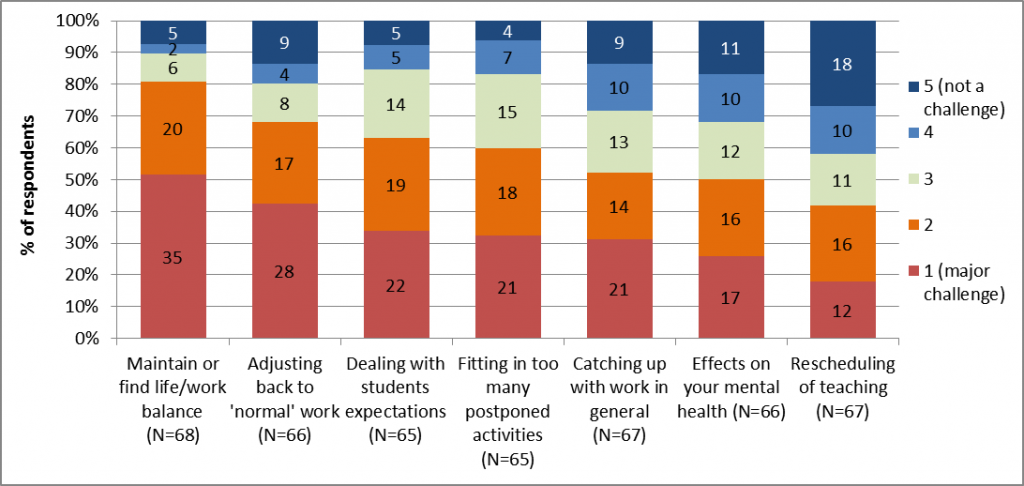

Finding or maintaining work-life balance when lockdown ends was identified as a major challenge by 51% of respondents (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Major challenges identified regarding work at the end of lockdown.

Figure 6. Major challenges identified regarding work at the end of lockdown.

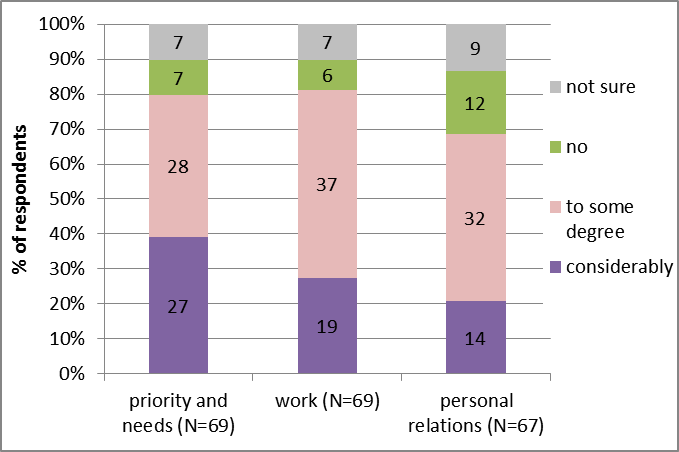

80% or more of respondents think the C-19 outbreak has brought long-lasting changes in their attitude to ‘priorities and needs’ and work, considerably for 27% and 19% of respondents, respectively (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Perception of long-lasting changes brought by the C-19 outbreak.

Figure 7. Perception of long-lasting changes brought by the C-19 outbreak.

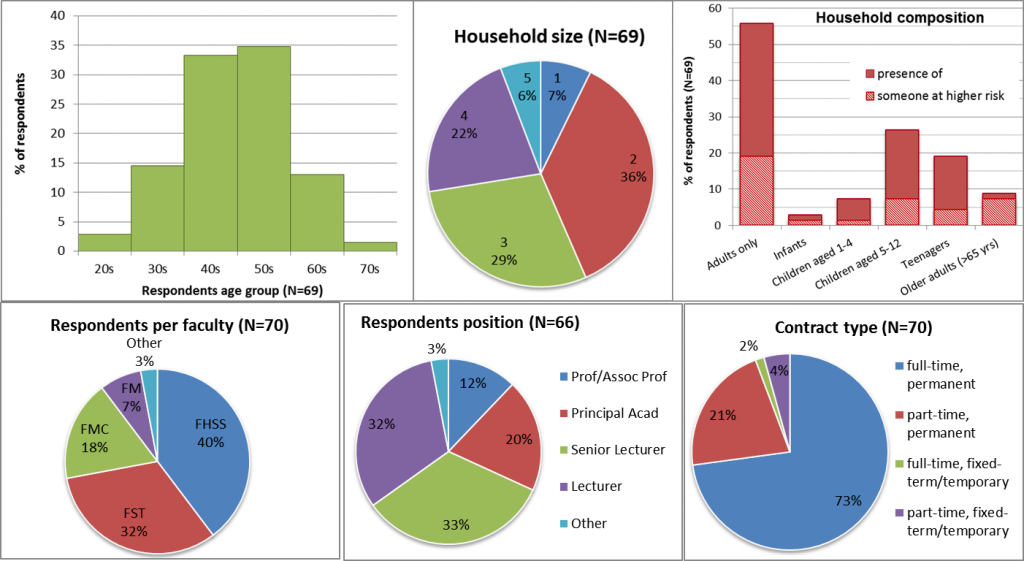

Who are the respondents?

Exposure to Covid-19

- 7% of respondents (5 out of 68) had severe symptoms of Covid-19 or tested positive or live with someone who did. All are female respondents in their 20s, 30s and 50s.

- 22% of respondents (15 out of 68) had close family members, friends or colleagues who had severe symptoms of Covid-19 or tested positive. All are female respondents in their 30s, 40s and 50s (the majority, 10 respondents).

- 41% of respondents (28 out of 68) live in a household where there is at least one person at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19.

Just over a month ago, RDS created a

Just over a month ago, RDS created a  The EC and EU member states have launched a new data-sharing platform ‘

The EC and EU member states have launched a new data-sharing platform ‘ UKRI have created a website called:

UKRI have created a website called:

On 6 April, BU launched a COVID-19 internal competition, with a call for EoIs. This opportunity is open to all staff. The EoI deadline is at 23.59 on Tuesday, 14 April, and the winners will be announced on Tuesday, 20 April.

On 6 April, BU launched a COVID-19 internal competition, with a call for EoIs. This opportunity is open to all staff. The EoI deadline is at 23.59 on Tuesday, 14 April, and the winners will be announced on Tuesday, 20 April. RDS have created a

RDS have created a

w weeks, Parliament has seen a surge in need for access to research expertise as it engages with the COVID-19 outbreak.

w weeks, Parliament has seen a surge in need for access to research expertise as it engages with the COVID-19 outbreak.

From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives: Reflections from the SPROUT Network Event

From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives: Reflections from the SPROUT Network Event REF Code of Practice consultation is open!

REF Code of Practice consultation is open! BU Leads AI-Driven Work Package in EU Horizon SUSHEAS Project

BU Leads AI-Driven Work Package in EU Horizon SUSHEAS Project Evidence Synthesis Centre open at Kathmandu University

Evidence Synthesis Centre open at Kathmandu University ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease