Kate Welham, Professor of Archaeological Sciences at BU, has been appointed as chair of one of the 34 sub-panels that will assess research from universities across the country for the next Research Excellence Framework assessment in 2029.

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the UK’s system for assessing the excellence of research in UK higher education providers and is managed by Research England.

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the UK’s system for assessing the excellence of research in UK higher education providers and is managed by Research England.

The outcomes from REF assessments are used to inform the allocation of around £2 billion per year of public funding for universities’ research.

Professor Welham will lead the assessment for Archaeology.

Her role as chair will involve appointing the other members of her sub-panel and developing the criteria they will use to assess submissions. She will then work with her panel on rigorous evaluating submissions against those criteria and providing advice to the main panels on the quality of research.

After her appointment was announced, Professor Welham said: “I’m honoured to be invited to serve as chair of the archaeology Sub-Panel for REF2029. This is a valuable opportunity to support our discipline and ensure that its excellence—wherever and however it is expressed—is recognised fairly and consistently.

“Archaeology in the UK is a wide-ranging and globally engaged field, and I look forward to drawing on my experience from REF2021 and the current PCE pilot to help foster a collaborative and transparent process that delivers a rigorous and trusted assessment.”

Professor Welham’s appointment was made by the four UK higher education funding bodies – Research England, Scottish Funding Council, the Commission for Tertiary Education and Research in Wales and the Department for the Economy in Northern Ireland – and the REF Main Panel Chairs.

REF Director Rebecca Fairbairn said: “I’m delighted to welcome this outstanding group to lead the REF 2029 sub-panels. Their deep expertise and broad perspectives will be central to building an assessment process that is fair, rigorous, and trusted by the research community.

“We have been working in partnership with the sector throughout this process, and I’m grateful to everyone who expressed interest – your engagement is what strengthens the credibility and value of the REF across our research landscape.”

The latest issue of

The latest issue of  Laura Stedman reports on the global variance in screening approaches and diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). She explores the impact of these differences on policy recommendations and practice. Without a universally accepted screening criterion, the variance in approaches makes accurately calculating the prevalence of GDM difficult. Untreated GDM results in women being more likely to experience pre-eclampsia, caesarean birth or stillbirth, while babies are more likely to be born prematurely, macrosomic or large for gestational age.

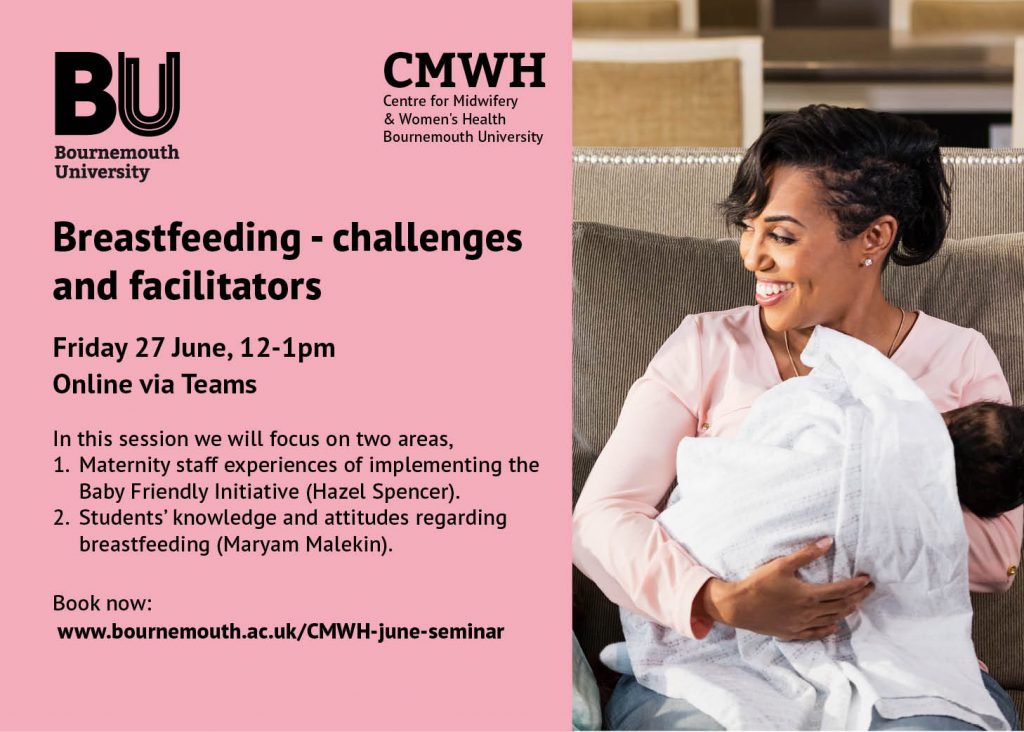

Laura Stedman reports on the global variance in screening approaches and diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). She explores the impact of these differences on policy recommendations and practice. Without a universally accepted screening criterion, the variance in approaches makes accurately calculating the prevalence of GDM difficult. Untreated GDM results in women being more likely to experience pre-eclampsia, caesarean birth or stillbirth, while babies are more likely to be born prematurely, macrosomic or large for gestational age. Also in this issue, Maryam Malekian, a MRes student in CMWH, has had her scoping review protocol published. Maryam has recently completed the review looking at knowledge and attitudes of nulliparous women regarding breastfeeding. She presented this work at the Maternal, Parental and Infant Nutrition and Nurture Unit (MAINN) Conference in April and has submitted the findings for publication.

Also in this issue, Maryam Malekian, a MRes student in CMWH, has had her scoping review protocol published. Maryam has recently completed the review looking at knowledge and attitudes of nulliparous women regarding breastfeeding. She presented this work at the Maternal, Parental and Infant Nutrition and Nurture Unit (MAINN) Conference in April and has submitted the findings for publication.

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the UK’s system for assessing the excellence of research in UK higher education providers and is managed by Research England.

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the UK’s system for assessing the excellence of research in UK higher education providers and is managed by Research England.

Visiting Prof. Sujan Marahatta presenting at BU

Visiting Prof. Sujan Marahatta presenting at BU 3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Friday 20 March 1-2pm

3C Event: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Friday 20 March 1-2pm Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop

Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching

UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease