Bournemouth University (BU), in partnership with the University of Port Harcourt (UPH) in Nigeria, is leading a transformative project to address gender disparities in higher education institutions (HEIs). Funded through the British Council’s Gender Equality Partnerships Grant, with a project value of £24,869.20, this initiative seeks to foster inclusivity and tackle systemic barriers such as underrepresentation of women in leadership and STEM disciplines, work-life balance challenges, and limited access to opportunities.

The project is led by Dr. Anthony Ezenwa (Bournemouth University) as the Principal Investigator, with Professor Huoma Worlu (UPH) leading the partner institution team and Professor Olufemi M. Adesope (UPH) serving as the Project Manager. Employing a mixed-methods approach, the research combines surveys, focus groups, interviews, and institutional analysis to identify gender disparities and co-create actionable policies. Capacity-building training sessions will empower faculty, staff, and students to promote gender sensitivity, inclusive leadership, and advocacy within their academic and professional spaces.

As Dr. Anthony Ezenwa and Team reflect, “This initiative provides an opportunity to close critical gaps in leadership, STEM participation, and institutional inclusivity while driving meaningful, scalable change for HEIs in the Global South.”

The project, expected to run until December 2025, will deliver a robust Gender Equality Policy, pilot implementation frameworks, and practical recommendations to improve gender equity in UPH. The findings aim to inform similar HEIs in developing societies globally, offering a replicable model to advance gender inclusivity in higher education.

Stay tuned for updates on this collaborative effort as we progress towards a more inclusive and equitable academic environment.

30 early career academics from ten London universities came together on the 26-27 November at Greenwich University for a two-day interdisciplinary sandpit funded by

30 early career academics from ten London universities came together on the 26-27 November at Greenwich University for a two-day interdisciplinary sandpit funded by  The participants specialised in a variety of disciplines such as psychology, anthropology, policy studies, performance, media, tourism, environmental sciences, architecture and law. They brought their interests in a sustainable world and society (as represented by the

The participants specialised in a variety of disciplines such as psychology, anthropology, policy studies, performance, media, tourism, environmental sciences, architecture and law. They brought their interests in a sustainable world and society (as represented by the  experts provided mentorship and feedback on the projects as they developed toward funding proposals. Two sandpit follow-up sessions will also aid the participants in developing their funding proposals.

experts provided mentorship and feedback on the projects as they developed toward funding proposals. Two sandpit follow-up sessions will also aid the participants in developing their funding proposals.

Dr Julia Round of the Faculty of Media and Communication has been awarded a 2024 Comics Education Kinnard Award for outstanding work with comics and education.

Dr Julia Round of the Faculty of Media and Communication has been awarded a 2024 Comics Education Kinnard Award for outstanding work with comics and education.

Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March

Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward?

Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward? BU academics in the news in Nepal

BU academics in the news in Nepal New CMWH paper on maternity care

New CMWH paper on maternity care ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

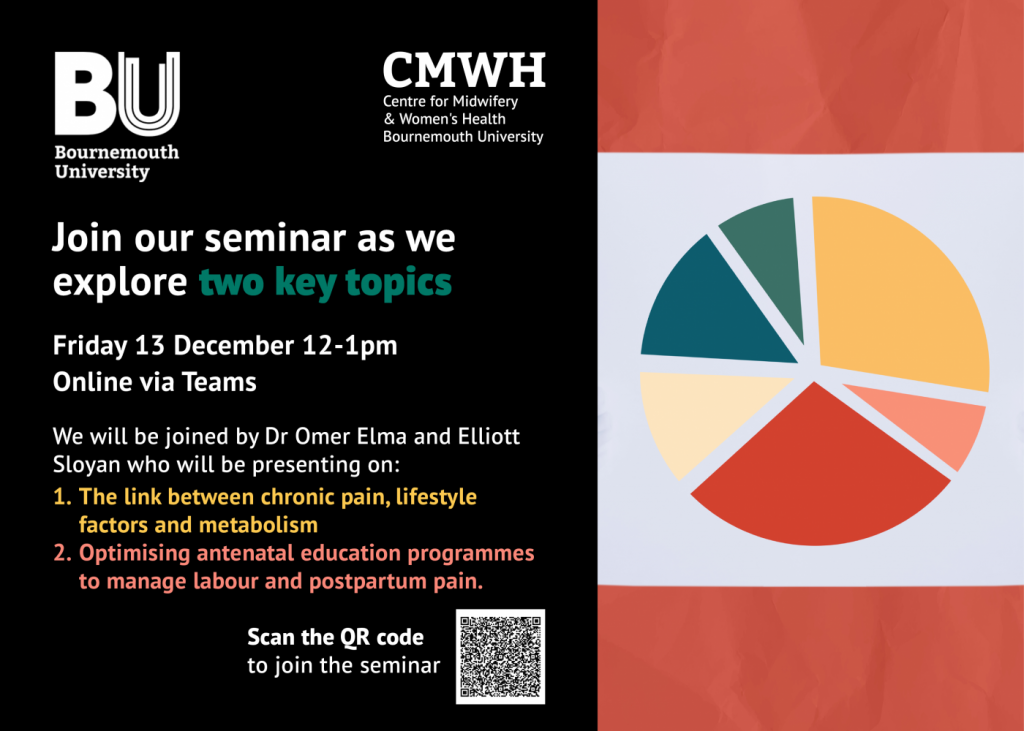

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease