Part 1: Developing insights into the world of the working carer

Background

Earlier this year we completed a study exploring the experiences of working carers in the South of England – part of a larger research project funded by NIHR ARC Wessex exploring carers needs, experiences and ideas about improving carers involvement in research (Pulman and Fenge, 2025).

A carer is anyone who provides unpaid care to a family member, partner, or friend who is unable to manage without support due to an illness, frailty, disability, mental health issue, or addiction.

Caring, unpaid, for older, disabled or chronically ill relatives or friends is something most of us will experience in our lives – all of us has a two in three chance of doing so. (HM Gov, 2023)

Carers who work in addition to their caring responsibilities – known as working carers – often face an ongoing struggle when trying to combine the dual demands of providing care with paid employment. There are nearly 3.7 million working carers in England and Wales; 2.6 million (72%) of these working in full-time paid employment alongside their caring roles, whilst about 1.6 million carers have problems combining work and care (Austin and Heyes, 2020).

The purpose of our research was to understand the experience of being in paid employment whilst providing unpaid care to someone, including adjustments made to employment, support provided by employers and support agencies, the impact on the carers perceived wellbeing and ideas for improving their involvement in carers research.

Realities of combining working with caring

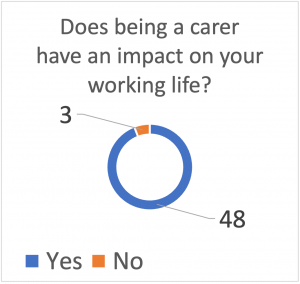

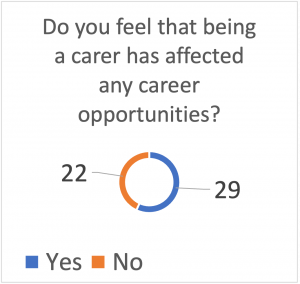

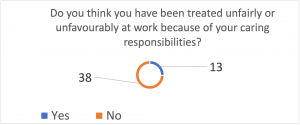

Initial exploratory PPI work was carried out between September and December 2024 – including n=6 unpaid carers attending a one and a half hour facilitated workshop where they contributed to the design and development of the initial draft of the online questionnaire. Data was collected between December 2024 and May 2025, with n=51 working carers completing our online survey.

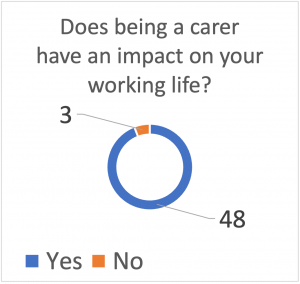

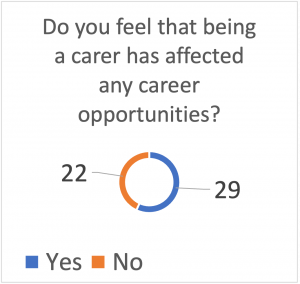

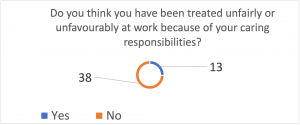

We found:

Several themes emerged concerning the carers experience at work, the support mechanisms in place which were helpful to them, issues and challenges experienced and ranked suggestions for future research to develop further understanding of the world of the working carer.

Our research highlighted the importance of developing more humanised ways of employers understanding a working carer’s needs and to meaningfully assist them in meeting their full potential within the workforce.

Employers need to think and plan differently for people with unpaid caring responsibilities and realise that working carers need more:

- ENGAGEMENT from employers about how they can stay in work and be supported.

- EMPATHY from employers regarding their caring responsibilities and demands.

- EQUALITY from employers, showing respect and giving carers opportunities to thrive.

Increasing empathetic understanding

Participants in our study (Pulman and Fenge, 2025) felt that it was difficult for some managers and colleagues to fully appreciate working carer experiences unless they had personal experience of a similar situation. This highlights the need for more training for line managers and the wider workforce about the needs and experiences of working carers to promote supportive working environments.

Enhanced training about working carer lived experience, including examples from film and television, innovative higher education eLearning techniques, mixed media, or listening to carer experiences face-to-face could be very beneficial in helping managers and the wider workforce to become more aware of and immersed in the lifeworld of a carer (Todres and Galvin, 2006; Pulman, Todres and Galvin, 2010).

With these approaches in mind, we wanted to reach corporate hearts and change ‘head in the sand’ mindsets by evoking a sense of common connection. To engage with, and communicate to, employers across the Wessex region using innovative visual approaches which would help to open a window on the hidden world of the working carer.

An opportunity to collaborate with local artists

In June, Professor Mel Hughes and Dr Gladys Yinusa invited expressions of interest from university researchers to work with local artists to produce a creative output which would help maximise the reach and impact of current research projects. The pilot project being a collaboration with BEAF Arts Co, an open-access, multi-art form festival and year-round arts programme based in Boscombe.

BEAF (2025) are an innovative and independent organisation of freelancers and volunteers, who feel passionately that culture changes communities for the better and there is a strong evidence base for creative outputs being an inclusive tool for reaching and involving communities in research and for extending the reach of research findings, including to community, academic, policy and practice audiences.

The pilot was developed to build connections with a local artist network who would be involved in selecting their preferred research project – matching the research team with a local artist and then providing funding to cover artist fees and materials. After successfully applying for funding for our research project, we were matched with artist Adilson Naueji to communicate findings.

We look forward to sharing reflections from this collaborative project in the second part of this blog post series soon.

With thanks to:

- Artist Adilson Naueji.

- The working carer research project is supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) Wessex.

- The artwork being created is supported by BEAF Arts Co and Bournemouth University.

More information on our project:

Professor Lee-Ann Fenge – lfenge@bournemouth.ac.uk

Dr Andy Pulman – apulman@bournemouth.ac.uk

https://nccdsw.co.uk/clusters/research/carer-research

https://www.arc-wx.nihr.ac.uk/social-care

References:

Austin, A. and Heyes, J., 2020. Supporting working carers: How employers and employees can benefit. CIPD/University of Sheffield.

BEAF Arts Co (2025). BEAF Arts Co Homepage, available online at: https://gotbeaf.co.uk/ (accessed September 30, 2025).

HM Gov (2023). Carers Week 2023: crunching the numbers… HM Gov Social Care Blog, available online at: https://socialcare.blog.gov.uk/2023/06/09/carers-week-crunching-the-numbers/ (accessed September 30, 2025).

Pulman, A. and Fenge, L.-A., 2025. Caring and working: developing insights into the world of the working carer. Health & Social Care in the Community.

Pulman, A., Todres, L., & Galvin, K. (2010). The carer’s world: An interactive reusable learning object. Dementia, 9(4), 535-547.

Todres, L., & Galvin, K. (2006). Caring for a partner with Alzheimer’s disease: Intimacy, loss and the life that is possible. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 1, 50–61.

Sara was presenting her doctoral work where she has used appreciative inquiry to explore midwives’ experience and processing following the occurrence of Obstetric Anal Sphincter injury (OASI) during spontaneous vaginal birth. Sara said that she found the conference and networking opportunities “inspiring and helpful for her PhD.”

Sara was presenting her doctoral work where she has used appreciative inquiry to explore midwives’ experience and processing following the occurrence of Obstetric Anal Sphincter injury (OASI) during spontaneous vaginal birth. Sara said that she found the conference and networking opportunities “inspiring and helpful for her PhD.”

Dr Demetra Andreou and Prof Genoveva Esteban from the School of Life and Environmental Sciences recently welcomed Sixth Form students and science teachers from Thomas Hardye School (Dorchester) to a full-day workshop on the molecular ecology of freshwater shrimps. The academics offered a hands-on computational investigation of biodiversity, demonstrating how DNA analysis can reveal population structures, detect potential invasive species, and inform conservation strategies in freshwater ecosystems.

Dr Demetra Andreou and Prof Genoveva Esteban from the School of Life and Environmental Sciences recently welcomed Sixth Form students and science teachers from Thomas Hardye School (Dorchester) to a full-day workshop on the molecular ecology of freshwater shrimps. The academics offered a hands-on computational investigation of biodiversity, demonstrating how DNA analysis can reveal population structures, detect potential invasive species, and inform conservation strategies in freshwater ecosystems.

Prof Marahatta promoting BU-Nepal collaboration

Prof Marahatta promoting BU-Nepal collaboration 3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm

3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March

Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward?

Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward? ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease