BU’s Sascha Dov Bachmann presents on Hybrid Warfare at UNG, USA

Latest research and knowledge exchange news at Bournemouth University

Are you interested in engaging the public with your research but have no idea where to begin? Do you already have an idea for a public engagement event and want to make it a reality? If you’ve answered yes– or even maybe– to either of these questions then our forthcoming workshop on Developing a Public Engagement Event is for you!

Our workshop offers a step-by-step, practical guide to turning your research into a fully-fledged public engagement activity through a series of interactive talks, hands-on activities and take-away resources that will help guide the way through the murky world of engaging with the general public.

The session will explore:

By the end of the session you should feel fully equipped to deliver some public engagement with research and feel confident to participate in some of our upcoming events.

The session will run from 1pm – 4pm on Wednesday 15th November 2017 on Talbot campus (room tbc). To find out more and book your place, click here.

If you want to arrange a more 1-2-1, tailored session around public engagement with your research, or would just like to chat through some ideas, we are always available to provide support. Just drop Natt Day (our Engagement Officer) an email and she’ll be in touch.

The Doctoral C ollege would like to present the new 2017 / 2018 Researcher Development Programme

ollege would like to present the new 2017 / 2018 Researcher Development Programme

This monthly update is for PGRs and their supervisors to outline upcoming research skills and development opportunities including events, workshops and networking opportunities supported by the Doctoral College. In this update we would like to introduce the inaugural 3 Minute Thesis (3MT®) event and R.E.D talks, alongside the Researcher Development Programme for 2017-18, the 10th Annual Postgraduate Conference and Santander Mobility Fund. These exciting development opportunities are taking place now so check out our application processes and booking information to advance your current skills, knowledge and networks.

Don’t forget to check out out the Doctoral College Facebook page and Researcher Development Hub on the website.

The Société Française pour l’Etude des Lipides (SFEL) recently held the fourth iteration of their Lipids and Brain conference in Nancy France.

I was given the opportunity to present some preliminary results from an ongoing study I am conducting as part of my PhD, looking into the effects of a multi-nutrient omega-3 fatty acid supplement and exercise on mobility and cognitive function in ladies aged 60+. Analysis of the baseline data revealed relationships between levels of omega-3 fatty acids in the blood with cognitive and gait outcomes, however this effect differed between non-frail and pre-frail participants.

I was given the opportunity to present some preliminary results from an ongoing study I am conducting as part of my PhD, looking into the effects of a multi-nutrient omega-3 fatty acid supplement and exercise on mobility and cognitive function in ladies aged 60+. Analysis of the baseline data revealed relationships between levels of omega-3 fatty acids in the blood with cognitive and gait outcomes, however this effect differed between non-frail and pre-frail participants.

The conference brought together scientists, physicians and nutritionists to provide a unique prospective on the role of lipid nutrition in the prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases with a large focus on Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). The conference was a mix of lectures, invited reviews, and poster sessions. There was a tremendous variety of topics presented, including lectures on the pathophysiology and epidemiology of AD, how AD can impact lipid metabolism and the effects of lipid intake on prevention and treatment of AD.

During the conference Professor Stephen Cunnane from the Research Center on Aging, Sherbrooke (Canada) was presented with the prestigious Chevreul Medal.

On a personal note this was an exciting opportunity for me to present my work and represent Bournemouth University and my supervisory team of Dr. Simon Dyall and Dr. Fotini Tsofliou at a respected conference. It was very satisfying to see some interest in my work from researchers whose work I myself look up to.

I would like to extend my gratitude towards Bournemouth University, for providing the funding that allowed me to attend the conference and to the scientific committee at the SFEL for organising such an impeccable event.

If you would like to learn more about our research, please feel free to contact me at pfairbairn@bournemouth.ac.uk

Well, anyone who thought the Minister would have less to do in this session of Parliament, other than oversee the implementation of the Higher Education and Research Act, was underestimating him. Rather unexpectedly he demonstrated yesterday that he had fully embraced the Fusion model (he calls it a three legged stool) by announcing a new excellence framework for knowledge exchange to sit alongside REF and TEF. We have a bit on each, along with an update on that funding review (what funding review) and some other news.

REF, TEF (even when it’s TESOF, see below) and now the KEF….a new excellence framework has been announced by the Minister at the annual HEFCE conference.

Described by the Minster (apparently) as the “third leg of the HE stool” this new framework will be run by Research England (under its head (designate), David Sweeney, and also responsible for the REF). Like the REF, the KEF will have a clear cash “carrot” for participation and to motivate high performance – it will provide a new method for allocating Higher Education Innovation Funding (HEIF).

The story was all about the UK’s competitiveness. The Minister celebrated the quality of UK research but challenged the sector to have more connection to the wider world and impact on the economy, to justify the “outsize role” that universities play in Research and Development in the UK – compared to industry. He said:

Last week, Prof Ann Hemingway, Prof Adele Ladkin and Dr Holly Crossen-White joined European research colleagues in Ostend, Belgium for a SAIL Project bi-annual team meeting. Over two days all research partners from four different European countries had the opportunity to share their initial research data from pilot projects being developed within each country for older people. The BU team will be undertaking the feasibility study for the SAIL project and will be drawing together all the learning from the various interventions created by the other partners.

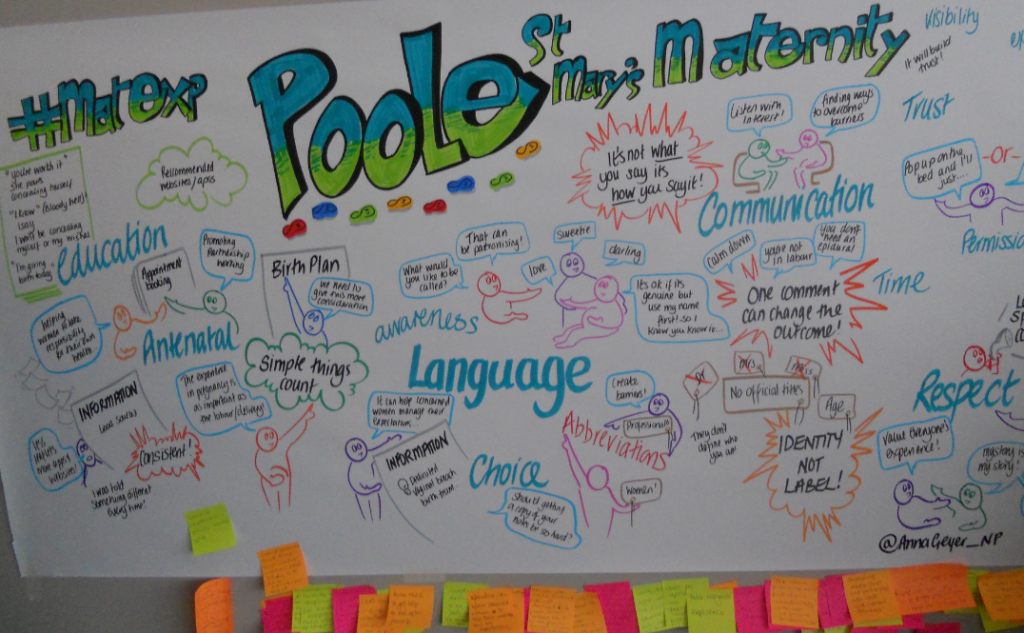

Friday 6th October St Mary’s Maternity Unit, part of Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, held a Whose Shoes? event in Poole. Whose Shoes?® is a facilitation tool to help empower both staff and service users of services. Friday’s event was led by Gill Phillips, the person behind the original idea of Whose Shoes?®. Gill’s approach involves promoting understanding and empathy by looking at issues from a wide range of perspectives from a range of possible stakeholders.

Friday 6th October St Mary’s Maternity Unit, part of Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, held a Whose Shoes? event in Poole. Whose Shoes?® is a facilitation tool to help empower both staff and service users of services. Friday’s event was led by Gill Phillips, the person behind the original idea of Whose Shoes?®. Gill’s approach involves promoting understanding and empathy by looking at issues from a wide range of perspectives from a range of possible stakeholders.

The event Poole was initiated by NHS midwife Jillian Ireland, who is also BU Visiting Faculty in our Centre for Midwifery, Maternal & Perinatal Health (CMMPH). She was assisted by Dr. Jen Leamon, who helped facilitate NHS maternity staff, pregnant women and new mothers, in their discussions. Jen is Senior Lecturer in Midwifery at BU and she facilitated the discussion with the aid of the Whose Shoes? board game. In the afternoon Prof. Edwin van Teijlingen (also based in CMMPH) led a discussion of reflection and reflective practice with midwives and maternity support workers (MSWs). CMMPH’s involvement in the event is part of our wider collaboration with the NHS locally in the field of midwifery education.

The Whose Shoes? board game is also by CMMPH in a very different context as PhD student Alice Ladur has translated the game to test it in Uganda. Alice first did a pilot study with African men living in London before embarking on a project to improve men’s involvement in maternity care in rural Uganda.

The Whose Shoes? board game is also by CMMPH in a very different context as PhD student Alice Ladur has translated the game to test it in Uganda. Alice first did a pilot study with African men living in London before embarking on a project to improve men’s involvement in maternity care in rural Uganda.

Congratulations to Taylor Cooper (BU Physiotherapy Graduate 2017) and Dr Jonathan Williams for their successful publication in Physical Therapy Reviews.

Their article entitled ‘Does an exercise programme integrating the Nintendo Wii Fit Balance Board improve balance in ambulatory children with Cerebral Palsy?’ was accepted this week. This was based on work carried out through the Level 6 unit, Research for Physiotherapy Practice.

Well done to you both – it’s great to see our students publishing so early in their career.

Clare Killingback

The Faculty of Health and Social Sciences Research Seminar Series will be starting again soon.

We noted that the best attended seminars last year were those involving a range of presentations in a one hour slot. These bite-size selections of research topics were great in attracting an audience from across disciplines and created a fun, friendly atmosphere.

To build on this we will be running monthly Research Seminars with 2-3 presenters at each session. These seminars are open to everyone, so whether this is your first venture into research or you are a veteran researcher please feel free to come along and share your experiences.

Seminars will be held between 1 and 2pm at the Lansdowne Campus on the following dates:

18th October 2017

15 November 2017

17 January 2018

21 February 2018

21 March 2018

18 April 2018

16 May 2018

20 June 2018

Details of presenters will be announced via the blog.

Any questions please feel free to email me at: ckillingback@bournemouth.ac.uk

The European Commission has pre-published, the Horizon 2020 Work Programme for ICT, with calls up to 2020. The finalised document is due to be released in October 2017, with calls due to open in the coming months with the first deadlines in April 2018. These calls will be available via the Participant Portal. This early notice may assist you in setting up new collaborations with a view to submission or match your existing research network connections. Please nogte that this document is still in draft so details may be subject to change prior to final publication.

The European Commission has pre-published, the Horizon 2020 Work Programme for ICT, with calls up to 2020. The finalised document is due to be released in October 2017, with calls due to open in the coming months with the first deadlines in April 2018. These calls will be available via the Participant Portal. This early notice may assist you in setting up new collaborations with a view to submission or match your existing research network connections. Please nogte that this document is still in draft so details may be subject to change prior to final publication.

Digital technologies underpin innovation and competitiveness across private and public sectors and enable scientific progress in all disciplines. The topics addressed in this Work Programme part cover the ICT technology in a comprehensive way, from technologies for Digitising European Industry, HPC, Big Data and Cloud, 5G and Next Generation Internet. Pursuing the change initiated under Work Programme 2016-2017, activities will continue to promote more innovation-orientation to ensure that the EU industry remains strong in the core technologies that are at the roots of future value chains.

Top level areas are:

CALL: Information and Communication Technologies

The Digitising European Industry initiative aims to establish next generation digital platforms and re-build the underlying digital supply chain on which all economic sectors are dependent. The initiative should enable all sector and application areas to adapt, transform and benefit from digitisation, notably by allowing also smaller players to capture value. Digital Platforms are becoming a key factor in one sector after another, enabling new types of services and applications, altering business models and creating new marketplaces. Actions under this heading will provide extensive support to key DEI components in Photonics, Robotics, Manufacturing technologies and Cyber-Physical Systems. Support to Micro-electronics, in particular for higher TRLs, will continue through the ECSEL Joint Undertaking. In addition, innovation hubs and platforms, two key DEI objectives, will be supported through a Focus Area on Digitisation and Transformation of the EU industry, implemented in cooperation with other programme parts.

The challenges to address are:

CALL: Digitising and transforming European industry and services: digital innovation hubs and platforms:

CALL: Digitising and transforming European industry and services: digital innovation hubs and platforms:

In April 2016, the Commission issued a communication outlining its strategy for allowing the European Union to fully seize the opportunities offered by digitisation across industrial and services sectors. Beyond the support to key technological areas, an essential aspect is to foster the uptake of digital technologies and innovations, as well as synergies with other key enabling technologies. The ‘digitising and transforming European industry and services’ focus area ambitions to support Horizon 2020’s contribution to the implementation of this strategy, through projects cutting across technological boundaries and reinforcing links between LEIT and Societal Challenges.

The activities within this call are:

CALL: Cybersecurity

Within the next decade cybersecurity and privacy technologies should become complementary enablers of the EU digital economy, ensuring a trusted networked ICT environment for governments, businesses and individuals. The EU ambition is to become a world leader in secure digital economy. Within this call, applications to increase system resilience, support privacy and countering cyber attacks.

CALL: EU-Japan Joint Call

Topics within this call are to include the hyper-connected society in the context of the Smart City and 5G applications and beyond.

CALL: EU-Korea Joint Call

Topics within this call are to include cloud-based technologies, Internet of things, AI and 5G technologies

Other activities are included in this pre-publication draft.

If you are considering applying to any of these calls, please contact Emily Cieciura, RKEO’s Research Facilitator for EU and International funding.

My name is Teodora Tepavicharova and I will be in my second year in September 2017. I have always been interested in Digitalisation and when I found out about the opportunity to work as an assistant for ‘Investigating Forms of Leadership in the Digital Age’ research project, I couldn’t be happier and more excited to apply for it. I knew that working on something like this is a big responsibility but being able to be part of a team of professionals from the area you are passionate about is definitely worth it! Let me explain you more about my experience as an Student Research Assistant.

What? The Student Research Assistant job role is a great opportunity no matter of the year of study. Every student who meets certain criteria can apply for it. My role for this project was to conduct literature reviews, collect data and make conclusions upon it. It was a challenge to find new information that hasn’t been researched before but working on the project, we found very interesting theories that may be a game changer for the way the Digital World has been looked up at until now. I found the foundation needed for the creation of an evaluative research paper on NVivo 11.

Why? The advantages of working this are many – make new contacts within the university and the environment where you are working, meeting new people, gaining new skills etc. In my opinion, one of the best things that you can learn is the information that you are looking for. I wanted to meet and work with tutors who will be teaching me in future and URA gave me this opportunity. Being able to dive so deep into a topic is a great way to learn new things, theory and real-life examples about something that you are passionate about. I found it very interesting to read and observe different papers, websites and get in touch with people who can give you inside of a brand-new topic is amazing experience for a student.

Where? The job is extremely flexible. Depending on you and the Project Leaders, you may choose to work from home, local web café, university or any other place where you can be productive. I worked from home and in the university depending on the amount of work I had. For me this was very useful because sometimes I needed much more time to work in the office rather than at home. Being able to choose makes the work pleasurable. I had my own desk, computer and needed materials for working productive.

Who? Every undergraduate and postgraduate taught student who is studying in the university and whose grades are 70 and above can apply for the position. At the end of my first year, I decided to work at least a month during the summer. The unique opportunity is great for everyone because no matter of your year of study, you always need experience in your CV. If you are curious, reliable, focused and enthusiastic, then definitely go for it!

When? I worked from the beginning to the end of June which again was my preferable time. This is another advantage of the job – you can spread the hours depending on your free time. Of course, it depends on the amount of work you have, the amount of time you spent working and the arrangements with your Project Leaders. The job was greater than my expectations as it was dynamic and I was able to learn how to work with NVivo 11.

I think that the most amazing thing about working as a SRA is that you are very welcomed to the team. My Project Leaders are wonderful, intelligent women who made me feel very calm, welcomed and helpful since day one. Being able to work in such cohesion, gives you the motivation and at the same time you are enjoying every moment of this journey. Working with NVivo 11 was a pleasure because it is easy to navigate and manage. I will certainly use the software again for my assignments and dissertation! So, if you are driven and ready to show what you are capable of, apply for Research Assistant!

The Faculty of Health and Social Sciences Research Seminar Series will be starting again in the coming academic year.

But first I’d like to say a big thank you again to all those who contributed to the seminars last year. We had a wonderful mixture of presentations and it was great to see the range of research going on in the faculty.

We noted that the best attended were those involving a range of presentations in a one hour slot. These bite-size selections of research topics were great in attracting an audience from across disciplines and created a fun, friendly atmosphere.

To build on this in the coming year we will be moving to monthly Research Seminars with 2-3 presenters at each session. These seminars are open to everyone, so whether this is your first venture into research or you are a veteran researcher please feel free to come along and share your experiences.

Seminars will be held on the first Wednesday of every month (second Wednesday in October) between 1 and 2pm at the Lansdowne Campus.

If you are interested in presenting please get in touch with Clare at: ckillingback@bournemouth.ac.uk

Dr Beukes (CEMIS, US), Dr S Bachmann (BU) and Prof Liebenberg (CEMIS, US)

The chapter is called, “Interplay between lipid mediators and the immune system in the promotion of brain repair”, and looks at the interactions of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids with endocannabinoids in neuroinflammation, neurogenesis and brain aging.

The brain is highly enriched in docosahexaenoic (DHA) and arachidonic (ARA) acids, omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), respectively. DHA and other long-chain omega-3 PUFAs are precursors of anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving mediators, whereas ARA is precursor of inflammatory eicosanoids, but also pro-resolving mediators. The endocannabinoid system comprises a group of bioactive lipids, receptors and enzymes involved in their synthesis and degradation. 2-archidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide (AEA) are the primary agonists of cannabinoid receptors in the brain, substrate for enzymes such as cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases and cytochrome P450 mixed function oxygenases, which release ARA upon hydrolysis. The aging brain has impaired ability to balance protective and detrimental effects of the immune system and chronic low-grade neuroinflammation is a contributor to cognitive impairment and development of neurodegenerative diseases. There is a complex interplay between omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs, the endocannabinoid system and the immune system. This chapter summarises current evidence of this interplay and discusses the therapeutic potential in the promotion of brain self-repair.

Dr Simon Dyall’s Bioactive Lipids Research Lab conducts research investigating the role of bioactive lipid mediators in brain protection and repair across the lifespan and following neurotrauma.

The book, Role of the Mediterranean Diet in the Brain and Neurodegenerative Disease” is edited by Farooqui T. and Farooqui A., and is due for publication 1st November 2017 by Academic Press. Paperback ISBN: 9780128119594

The Royal Society is looking for brilliant science and scientists to feature at the Summer Science Exhibition 2018.

The Royal Society is looking for brilliant science and scientists to feature at the Summer Science Exhibition 2018.

The Exhibition features the UK’s most inspiring research and is a chance for scientists to showcase their work to over 14,000 people, including everyone from school children and families to MPs and Fellows of the Royal Society. Exhibitors are supported throughout the process and get dedicated support, advice and guidance from our Exhibition team.

It’s a great event to be part of, but as our motto (Nullius in verba) urges, don’t take our word for it. A 2017 exhibitor said:

“The whole week of the exhibition was fabulous. All our team thoroughly enjoyed the event and it has been a memorable experience for us. We have learned a lot from this.”

The call for proposals closes on 1 September 2017 and the Exhibition will run from 2 – 8 July 2018.

If you are interested in finding out more or applying, please visit this website: https://royalsociety.org/science-events-and-lectures/2017/summer-science-exhibition/proposals/.

Please direct all enquiries to exhibition@royalsociety.org.

Public engagement team is currently looking for speakers for U3A Public Lectures day taking place on Monday 11th September at EBC.

The University of the Third Age are a community of retired/ semi retired people who enjoy the reward of learning and take part in regular groups and sessions to expand their skills and life experiences.

They are very enthusiastic audience so be prepared for lots of questions and interesting discussion about your research.

We are looking for talks that fit into the history theme as we’re inviting Boldre Parish Historical Society to join us, but if your research is not directly related we’d still love for you to be involved!

This is a half day event, however we only ask for you to be there for duration of your talk (30-40 minute talk followed by Q&A session)

If this sounds like something you would like to do or know someone who may be interested, please drop us an email – fol@bournemouth.ac.uk

We’re looking forward to hearing from you!

August is almost upon us and that means before you know it the Bournemouth Air Festival will be upon us.

August is almost upon us and that means before you know it the Bournemouth Air Festival will be upon us.

We are still looking for hands-on activities to come join us at the Air Festival as we run their first ever Science Tent with support from the British Science Association and Siemens UK.

We’re looking for interactive and engaging activities or exhibits that:

If you have an activity that fits this criteria– or even an idea for an activity that would fit this criteria and would like advice and support to design and deliver it– then contact Natt (nday@bournemouth.ac.uk) to express your interest.

We are also still recruiting individuals to try their hand at Science Busking for the Air Festival. No previous experience is required as we will be providing full training and busking activities for you. You just have to be a friendly, approachable individual who wants to engage with the public at the Festival. If this sounds like you– again, contact Natt (nday@bournemouth.ac.uk)