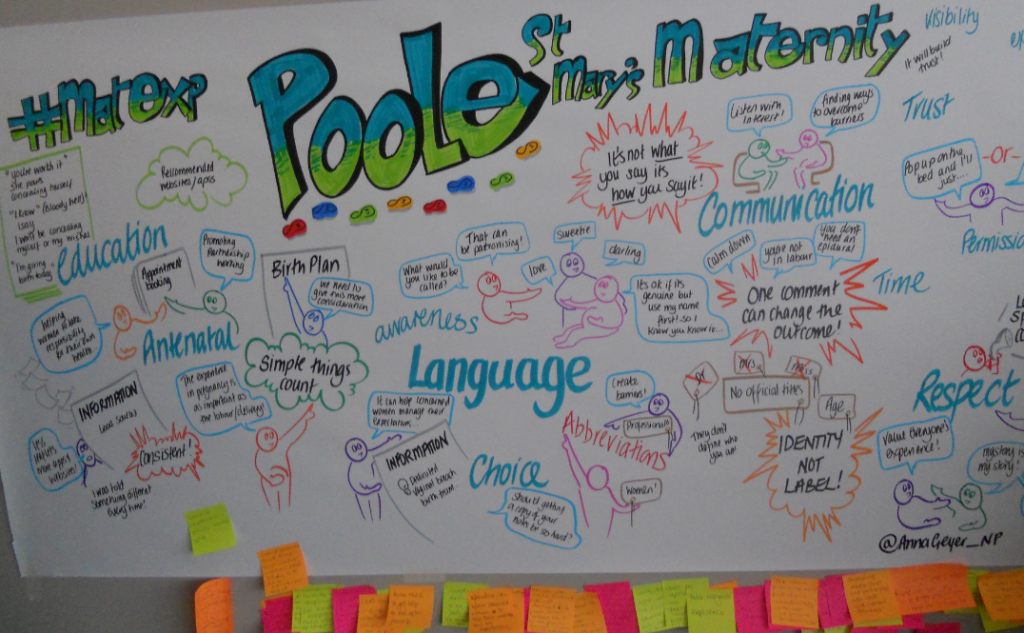

The Normal birth research conference is an annual, international event that takes place to focus on less complicated aspects of pregnancy and birth. This year it took place in the beautiful surroundings of Grange-over-sands overlooking Morecambe bay and on the edge of the Lake District. On this occasion there were delegates from over 20 countries including Canada, USA, New Zealand, Australia, Brazil, Poland, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway and India! The attendees included midwives, obstetricians, birth supporters, architects, artists, geographers and educators as well as representatives of the World Health organisation, charities and Baroness Cumberlege from the UK House of Lords.

Sara Stride, Jenny Hall, and Jane Fry at the conference

Research at Bournemouth University was well represented from CMMPH, CQR and CEL. Midwifery lecturer, Sara stride, on behalf of the research team of Professor Vanora Hundley and Dr Sue Way, presented a poster of their work, ‘a qualitative study to explore UK midwives’ individual practice, beliefs and attitudes regarding perineal care at the time of birth’. Dr Jane Fry, also from the midwifery team, presented a research topic on her Doctoral work, ‘ A descriptive phenomenological study of independent midwives’ use of intuition as an authoritative form of knowledge during women’s labours and births’. She also facilitated a workshop titled ‘ Finding your own intuition: a workshop designed to explore practitioners’ ways of knowing during childbirth’ .

Jenny Hall with Professor Susan Crowther at the book launch [(c) Sheena Byrom]

The impression taken away was the passion and importance of more evidence required around more ‘normal’ aspects of pregnancy and birth, especially in countries with less resources. There is considerable humanising of care being carried out internationally, and is a key focus at the World health organisation. A focus for the UK midwifery is current maternity services transformation, yet much of the global focus is on the importance of transformation in line with the recent Lancet series on maternity, and international collaboration to achieve the goals for Sustainable development. As a force, the team behind normal birth research serve this area powerfully, in informing care for women, babies and families across the global arena. The final rousing talk by Australian professor Hannah Dahlen, to the current backlash to ‘normal birth’ in the media was inspiring and is an editorial in the international journal Women and Birth. Next year the conference is in Michigan, USA!

We know that public health works and thinks long-term. We’ll typically see the population benefits of reducing health risks such as tobacco use, obesity and high alcohol intake in ten or twenty years’ time. But we often forget that preceding public health research into the determinants of ill health and the possible public health solutions is also slow working. Evidence-based public health solutions can be unpopular with voters, politicians or commercial companies (or all). Hence these take time to get accepted by the various stakeholders and make their way into policies.

We know that public health works and thinks long-term. We’ll typically see the population benefits of reducing health risks such as tobacco use, obesity and high alcohol intake in ten or twenty years’ time. But we often forget that preceding public health research into the determinants of ill health and the possible public health solutions is also slow working. Evidence-based public health solutions can be unpopular with voters, politicians or commercial companies (or all). Hence these take time to get accepted by the various stakeholders and make their way into policies. I was, therefore, glad to see that Scotland won the Supreme Court case today in favour of a minimum price for a unit of alcohol. As we know from the media, the court case took five years. Before that the preparation and drafting of the legislation took years, and some of the original research took place long before that. Together with colleagues at the Health Economic Research Unit at the University of Aberdeen, the University of York and Health Education Board for Scotland, we conducted a literature review on Effective & Cost-Effective Measures to Reduce Alcohol Misuse in Scotland as early as 2001 [1]. Some of the initial research was so long ago it was conducted for the Scottish Executive, before it was even renamed the Scottish Government.

I was, therefore, glad to see that Scotland won the Supreme Court case today in favour of a minimum price for a unit of alcohol. As we know from the media, the court case took five years. Before that the preparation and drafting of the legislation took years, and some of the original research took place long before that. Together with colleagues at the Health Economic Research Unit at the University of Aberdeen, the University of York and Health Education Board for Scotland, we conducted a literature review on Effective & Cost-Effective Measures to Reduce Alcohol Misuse in Scotland as early as 2001 [1]. Some of the initial research was so long ago it was conducted for the Scottish Executive, before it was even renamed the Scottish Government.

n Sunday BU and RSPB staff along with volunteers from SUBU enjoyed hearing what young people under 12 years old thought about about being outdoors.

n Sunday BU and RSPB staff along with volunteers from SUBU enjoyed hearing what young people under 12 years old thought about about being outdoors. Recently, I was fortune enough to become the Research Assistant on the HEIF-6 project run by Dr Ben Hicks. This is a one year project that aims to develop and evaluate a free Virtual Learning Environment tool that will support practitioners and care home staff wishing to use commercial gaming technology (iPads, Nintendo Wii) with people with dementia and their care partners. We have a number of experts involved in the research, such as Dr Samuel Nyman from Psychology Department and ADRC, Professor Wen Tang from Department of Creative Technology, Dr Sarah Thomas who is Deputy Director BUCRU and Dr Clare Cutler who is Research Skills and Development Officer. We also collaborate with Alive! who are a charity dedicated to improving the lives of older people and people with dementia through delivering innovative activities (e.g. the use of technology) and training dementia care practitioners. They work with 350 Care Homes and Day Centers across the South West of England and we are lucky to have Malcolm Burgin onboard who as the Regional Manager of Alive!.

Recently, I was fortune enough to become the Research Assistant on the HEIF-6 project run by Dr Ben Hicks. This is a one year project that aims to develop and evaluate a free Virtual Learning Environment tool that will support practitioners and care home staff wishing to use commercial gaming technology (iPads, Nintendo Wii) with people with dementia and their care partners. We have a number of experts involved in the research, such as Dr Samuel Nyman from Psychology Department and ADRC, Professor Wen Tang from Department of Creative Technology, Dr Sarah Thomas who is Deputy Director BUCRU and Dr Clare Cutler who is Research Skills and Development Officer. We also collaborate with Alive! who are a charity dedicated to improving the lives of older people and people with dementia through delivering innovative activities (e.g. the use of technology) and training dementia care practitioners. They work with 350 Care Homes and Day Centers across the South West of England and we are lucky to have Malcolm Burgin onboard who as the Regional Manager of Alive!.  Organised by Dr Ambrose Seddon (

Organised by Dr Ambrose Seddon (

REF Code of Practice consultation is open!

REF Code of Practice consultation is open! BU Leads AI-Driven Work Package in EU Horizon SUSHEAS Project

BU Leads AI-Driven Work Package in EU Horizon SUSHEAS Project Evidence Synthesis Centre open at Kathmandu University

Evidence Synthesis Centre open at Kathmandu University Expand Your Impact: Collaboration and Networking Workshops for Researchers

Expand Your Impact: Collaboration and Networking Workshops for Researchers ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease