Supported by the ECR Research Culture and Community Grant, Tom Cousins (Faculty of Health, Environment & Medical Sciences) recently organised a public lecture and book launch to celebrate the publication of research on the Swash Channel Wreck. This event served as a major milestone for a project that has spanned Tom’s entire career at Bournemouth University, from his time as an undergraduate and postgraduate student to his current role as a full-time member of the technical staff.

A Celebration of Maritime Archaeology

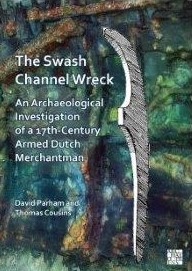

The Swash Channel Wreck Book

The event, held at Talbot Campus on 28 January, featured a well-attended public lecture and celebrated the launch of a new book by Dave Parham and Tom Cousins. The session featured an in-depth presentation on the Swash Channel Wreck, a 17th-century Dutch shipwreck first located in 1990 and rediscovered in 2006. As one of the most complete shipwrecks of its kind outside the Baltic, the site offers rare insights into 17th-century ship construction and life on board.

Combined with a display of archaeological finds, the event showcased years of research to members of the public and the wider BU community, including the University Executive Team and the Vice-Chancellor. The presentation was followed by a wine reception, allowing attendees to view the artifacts first-hand and discuss the findings

Beyond the university, the launch brought together long-term stakeholders from government agencies, harbour authorities, and museums. It was a reminder that the project was a shared effort, involving divers, students, and partners across two countries. Seeing everyone reunite to mark the publication, highlighted the project’s lasting significance for BU’s maritime archaeology and all who contributed to its journey.

Presenting the history of the Swash Channel Wreck during a public lecture, followed by a networking session where researchers, stakeholders, and the public gathered to celebrate the project’s milestone.

Supporting the research community

The launch was a collaborative effort that directly supported the development of early-career researchers and postgraduate students. Several PGRs and ECRs assisted in setting up and managing the day, providing them with valuable opportunities to network with members of the public, industry professionals, and senior university leadership.

Tom described the overall experience as “Interesting, welcoming, and collaborative,” noting that the greatest benefit was the opportunity to share this significant research with both the BU community and members of the public.

Apply for the ECR Research Culture and Community Grant

Do you have an idea for an event or initiative that could strengthen the research culture at BU? We invite you to follow in Tom’s footsteps and apply for funding to bring your project to life.

Find out more and submit your application here: Research Culture and Community Grant

Closing date 4pm, Monday 9 March 2026

If you would like to discuss your ideas before submitting your application, please contact Enrica Conrotto, Researcher Development Manager, at researcherdevelopment@bournemouth.ac.uk

Congratulations to Jonathan Parker, Ivan Gray, Andrew Morris and Sally Lee, the editors of the fourth edition of Newly-Qualified Social Workers: A Practice Guide to the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment [1]. This new edition has eleven chapters. Apart from the various chapters produced or co-produced by the editors, this 2026 text also include a chapter by two further Bournemouth University academics, including Dr. Richard Williams and Dr. Louise Oliver. The latter contributed ‘Chapter 7: Research and NQSW: Developing yourself as a research minded and critically reflective practitioner’.

Congratulations to Jonathan Parker, Ivan Gray, Andrew Morris and Sally Lee, the editors of the fourth edition of Newly-Qualified Social Workers: A Practice Guide to the Assessed and Supported Year in Employment [1]. This new edition has eleven chapters. Apart from the various chapters produced or co-produced by the editors, this 2026 text also include a chapter by two further Bournemouth University academics, including Dr. Richard Williams and Dr. Louise Oliver. The latter contributed ‘Chapter 7: Research and NQSW: Developing yourself as a research minded and critically reflective practitioner’.

Building on the success of the first SPROUT event in November 2025, registration is now open for the next session in the series.

Building on the success of the first SPROUT event in November 2025, registration is now open for the next session in the series. New view

New view

Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop

Beyond Academia: Exploring Career Options for Early Career Researchers – Online Workshop UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching

UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme: Deadline Approaching SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives

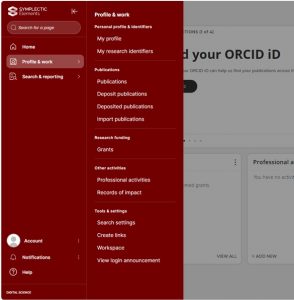

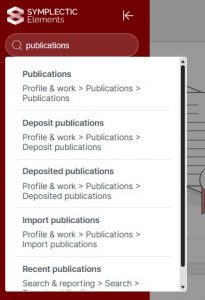

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives BRIAN upgrade and new look

BRIAN upgrade and new look Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh

Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease