Despite a near accident with a jug of milk, 30 cups and a projector screen twenty minutes before the start of the event, Wednesday’s open access (OA) publishing seminar was a huge success! Roughly 30 BU academics, researchers and PGR students attended the event which was aimed at increasing awareness, dispelling some of the myths, and demonstrating the benefits of open access publishing. There was also an opportunity for attendees to find out about the recently launched BU Open Access Publication Fund.

The event opened with a fantastic presentation by Dr Alma Swan (Key Perspectives Ltd) who spoke passionately about the benefits of open access publishing and archiving, showing clear demonstrations of how making your research available in open access outlets (and in BURO) dramatically increases the number of citations and leads to more people downloading the research papers. Of particular interest were her stats on who actually downloads open access papers published via the PubMed outlet: other academics and university students only account for 25% of downloads, and by far the biggest consumer of open access literature are ‘citizens’ (i.e. independent researchers, patients and their families, teachers, amateur or part-time researchers, other interested minds), who account for 40% of the research papers downloaded from PubMed. These are almost always people who would not normally have access to research published in traditional print journals.

The event opened with a fantastic presentation by Dr Alma Swan (Key Perspectives Ltd) who spoke passionately about the benefits of open access publishing and archiving, showing clear demonstrations of how making your research available in open access outlets (and in BURO) dramatically increases the number of citations and leads to more people downloading the research papers. Of particular interest were her stats on who actually downloads open access papers published via the PubMed outlet: other academics and university students only account for 25% of downloads, and by far the biggest consumer of open access literature are ‘citizens’ (i.e. independent researchers, patients and their families, teachers, amateur or part-time researchers, other interested minds), who account for 40% of the research papers downloaded from PubMed. These are almost always people who would not normally have access to research published in traditional print journals.

The second speaker was Willow Fuchs from the Centre for Research Communications (CRC) at the University of Nottingham. Willow gave an excellent presentation on the Sherpa Services that were developed and maintained by the CRC. These include RoMEO, Juliet and OpenDOAR. Authors can look up journals using the RoMEO database to check whether archiving in repositories is permitted (such as BURO) and, if so, what version of the paper can be made available. Authors can also easily check the publisher’s policies and see whether the journal offers a hybrid publishing option (i.e. the paper will still be published in the traditional print journal but will also be made freely available via the internet). It currently covers over 1,000 publishers and is an excellent source of information. Willow also mentioned the Juliet database which lists funder open access requirements, and the OpenDOAR database which is a searchable directory of open access repositories, such as BURO. All three of the Sherpa Service resources are freely accessible via the links in the text above.

The second speaker was Willow Fuchs from the Centre for Research Communications (CRC) at the University of Nottingham. Willow gave an excellent presentation on the Sherpa Services that were developed and maintained by the CRC. These include RoMEO, Juliet and OpenDOAR. Authors can look up journals using the RoMEO database to check whether archiving in repositories is permitted (such as BURO) and, if so, what version of the paper can be made available. Authors can also easily check the publisher’s policies and see whether the journal offers a hybrid publishing option (i.e. the paper will still be published in the traditional print journal but will also be made freely available via the internet). It currently covers over 1,000 publishers and is an excellent source of information. Willow also mentioned the Juliet database which lists funder open access requirements, and the OpenDOAR database which is a searchable directory of open access repositories, such as BURO. All three of the Sherpa Service resources are freely accessible via the links in the text above.

The event then focused on BU’s experience of open access publishing with presentations from Prof Edwin van Teijlingen and Prof Peter Thomas. Prof Edwin van Teijlingen (HSC) talked of the benefits of making his research findings freely available in terms of free access to the information, the quick turnaround times, and the high quality of the open access publications available in his field. Prof Peter Thomas primarily focused on the quick publication times which are particularly beneficial for the publication of the study protocols for the randomised control trials he has been involved with (his experience is that there is usually only 2-5 months between submitting the paper and its publication). He also displayed the access statistics from BioMed Central showing how many downloads there had been each month of his paper (between 18-77 downloads per month).

The event then focused on BU’s experience of open access publishing with presentations from Prof Edwin van Teijlingen and Prof Peter Thomas. Prof Edwin van Teijlingen (HSC) talked of the benefits of making his research findings freely available in terms of free access to the information, the quick turnaround times, and the high quality of the open access publications available in his field. Prof Peter Thomas primarily focused on the quick publication times which are particularly beneficial for the publication of the study protocols for the randomised control trials he has been involved with (his experience is that there is usually only 2-5 months between submitting the paper and its publication). He also displayed the access statistics from BioMed Central showing how many downloads there had been each month of his paper (between 18-77 downloads per month).

Prof Matthew Bennett closed the event by emphasising that the consumers of research not just academics; as BU moves to society-led research then the need to communicate research findings with non-academics will become even more important. He gave an overview of the recently launched BU Open Access Publication Fund, explaining how BU academics can access central funds to publish their papers in open access outlets (including traditional print journals with a hybrid option to make the paper freely available on the internet in addition to the print journal). Two BU academics have already benefited from the central fund and published their research in open access outlets – Prof Colin Pritchard (HSC) who published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, and Dr Julie Kirkby (DEC) who will shortly have a paper published by Plos ONE.

All in all this was an excellent event and a fabulous launch for the new open access fund! Expect to read more on open access publishing on the Blog over the coming months!

You can access the slides from the event from this I-drive folder: I:\CRKT\Public\RDU\Open access\event 261011

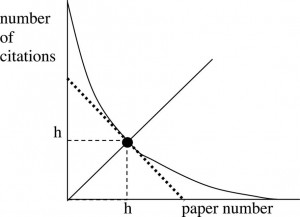

What are bibliometrics?

What are bibliometrics? Web of ScienceSM is hosted by Thomson Reuters and consists of various databases containing information gathered from thousands of scholarly journals, books, book series, reports, conference proceedings, and more:

Web of ScienceSM is hosted by Thomson Reuters and consists of various databases containing information gathered from thousands of scholarly journals, books, book series, reports, conference proceedings, and more:

Why do I need to think about the impact of my research?

Why do I need to think about the impact of my research?

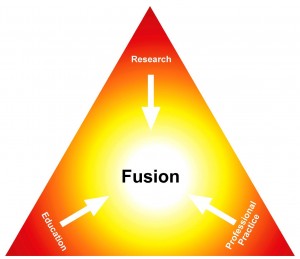

Starting later this term, the new BU Fusion Seminars aim to develop understanding within BU around the concept of Fusion, launched as part of the Vision & Values. The seminars, sponsored and led by UET, will be held monthly and aim to demonstrate examples of Fusion by highlighting instances of good practice at BU where education, research and professional practice have been successfully combined.

Starting later this term, the new BU Fusion Seminars aim to develop understanding within BU around the concept of Fusion, launched as part of the Vision & Values. The seminars, sponsored and led by UET, will be held monthly and aim to demonstrate examples of Fusion by highlighting instances of good practice at BU where education, research and professional practice have been successfully combined.

Prosopagnosia – or ‘face blindness’ – is a little known condition affecting 1 in 50 people. As Bournemouth University psychology lecturer Dr Sarah Bate explains, it is ‘literally a loss of memory for faces’.

Prosopagnosia – or ‘face blindness’ – is a little known condition affecting 1 in 50 people. As Bournemouth University psychology lecturer Dr Sarah Bate explains, it is ‘literally a loss of memory for faces’. Then we want to hear from you! 🙂

Then we want to hear from you! 🙂 Then come to our free Open Access event this Wednesday in the EBC!

Then come to our free Open Access event this Wednesday in the EBC!

Prof Marahatta promoting BU-Nepal collaboration

Prof Marahatta promoting BU-Nepal collaboration 3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm

3C Online Social: Research Culture, Community & Can you Guess Who? Thursday 26 March 1-2pm Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March

Final Call: UKCGE Recognised Research Supervision Programme – Deadline Monday 16 March Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward?

Interdisciplinary research: Not straightforward? ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Apply now ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease