Some fresh news and reports but overall a quieter week HE wise as the Government continues to focus on the rise in virus numbers nationally. Much of the media interest has focussed on familiar topics such as student complaints and white working class students. HEPI looked at future demand for HE study and UUK surveyed about modular study, have a new vision for the HE sector and talk international research partnerships.

The Policy Update is taking a break next week to coincide with the Parliamentary recess. See you all in November!

Spending Review

The Treasury has confirmed that the Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR) will cover a one year period to set Government department’s resource and capital budgets for 2021-22 due to the constraints of the pandemic. The Devolved Administration block grants will also be set for the same period. The exact date the CSR will be delivered hasn’t been confirmed but it is expected towards the end of November. The CSR focus is expected to cover:

- Providing multi-year NHS and schools’ resource settlements and priority infrastructure projects at full funding.

- Providing Government departments with the certainty they need to tackle Covid-19 and deliver the Government’s Plan for Jobs to support employment.

- Enhancing the vital public services to continue to fight against the virus alongside delivering first class frontline services.

- Investing in infrastructure as part of the levelling up agenda and to drive economic recovery and Build Back Better.

- Rishi Sunak, Chancellor, said:In the current environment it’s essential that we provide certainty. So we’ll be doing that for departments and all of the nations of the United Kingdom by setting budgets for next year, with a total focus on tackling Covid and delivering our Plan for Jobs. Long term investment in our country’s future is the right thing to do, especially in areas which are the cornerstone of our society like the NHS, schools and infrastructure. We’ll make sure these areas crucial to our economic recovery have their budgets set for further years so they can plan and help us Build Back Better.

Factors that will be of interest to HE that were meant to be included within the spending review are the Government’s response to the Augar review, response to the Pearce review of the TEF, and implications impacting on HE resulting from the Government’s already announced intentions for FE.

It isn’t clear whether the announcements over the last month on skills and technical education are it or whether there is more to come on FE. There was a debate on the role of colleges in a skills-led recovery from the Covid-19 outbreak this week. During the debate Robert Halfon (Education Committee Chair) welcomed the recently announced increases for FE funding and called for a long-term plan for FE, specifically a 10-year plan for college funding. Speaking about a previous Education Committee report he said:

- We found that sometimes initiative-itis was standing in for long-term vision and the sector needed more money going into the base rate of funding, over small pots of funding.

He also said:

- There is a social justice case for a pupil premium to support disadvantaged 16 to 19-year-olds. We have to get the basics right.

- I urge the Minister to consider whether the apprenticeship levy pot could be fine-tuned so that companies can use more of their levy if they hire younger people from 16 to 19 years, people from disadvantaged backgrounds and people who are going to meet our skills needs where we have huge skills deficits.

- We need to ensure that there is much closer collaboration between further education colleges and universities, because further education can play a major role in promoting degree apprenticeships—my two favourite words in the English language. Part of the £2.5 billion skills fund should be spent on covering training costs for small and medium-sized businesses taking on young apprentices.

- Finally, it would be very special to see institutes of technology across our landscape. We have done this before, with national colleges and other schemes. I urge the Minister to ensure that they are properly integrated into further education, and that they are further education institutes of technology, not just some brand new shiny buildings. Why not help them to build the prestige of further education?

A vision for universities

UUK also published Recovery, Skills, Knowledge and Opportunity – a vision for universities. It sets out what universities do now and do well and how as a sector we contribute to the economy, communities, the nation’s wellbeing, innovation and research. It also sets out a wish list series of reforms and recommendations for the future vision.

Below we list some of the recommendations within each section. As you read the recommendations you’ll spot several touch on the Augar Review’s recommendations and recent Government priorities and announcements such as FE & the Skills agenda.

- Economic recovery and levelling up

- Relax the eligibility criteria for financial support for higher education to enable greater access to short courses from level 4 and level 5 up to postgraduate study, specifically removing the requirements to i) study at an intensity of 25% or greater of a full-time equivalent course; and ii) follow a full course for a specified qualification.

- Modernise the regulatory system to recognise the level 4 and level 5 components of an undergraduate degree, not just as non-completion of level 6

- Make it easier for higher and further education providers to collaborate and deliver more flexible opportunities for upskilling and re-skilling locally

- address Sector Deals and integration with local Skills Advisory Panels,

- ongoing support for Institutes of Technology,

- ensuring that reforms at levels 4 and 5 allow learners to progress to technical, apprenticeship and more academically focused provision

- remove regulatory obstacles that hamper innovation and block partners working together

- Support a national graduate paid intern scheme, getting highly-skilled graduates into companies to help those businesses to thrive.

- Ensure that research funders meet more of the cost of research, and significantly grow flexible, excellence-driven and low-bureaucracy research funding for universities (known as quality-related research).

- Grow the Higher Education Innovation Fund (HEIF) in England. The removal of the lower thresholds in the fund should be considered to enable small, research-active universities to drive growth and support economic recovery in their localities.

- Equal chances: equality, diversity, inclusion and transforming lives

- Continue funding for collaborative partnerships between higher and further education providers and schools. This should include expanding opportunities for the most high-need schools to engage

- Introduce targeted maintenance grants for those students that need them the most and remove the financial barriers for those wanting to study flexibly, such as part time and mature students. Extend support for the additional costs of study via Childcare Grants and the Parents’ Learning Allowance to all students.

- No cut in real-terms funding per university student. This includes maintaining remaining government funding per student and the premium for supporting those from the most disadvantaged backgrounds

- No imposition of student numbers caps in England. Any government-enforced number caps would create new barriers to access and a cap on aspirations.

- A high-quality university experience for all students

- Work with students and universities on proposed reforms to the National Student Survey (NSS) to ensure that student feedback continues to play a role in driving up quality and providing useful information to students, while keeping the administrative burden to a minimum.

- Bureaucracy:

- not proceeding with subject-level TEF until the limitations of the methodology, its costs to universities and the taxpayer, and the actual value of its contribution to student decision-making in the wider student information landscape, have been fully considered

- using data and intelligence already available through other sources (e.g. UCAS) to minimise reporting demands

- OfS should not increase the bureaucracy burden when it adds new conditions or expands the regulatory framework

- The UK’s globally competitive position

- Prioritise full Association to the Horizon Europe and Erasmus+ programmes

- Ensure that funded contingency plans are in place should Association not be possible. Any funding to replace Horizon Europe should be additional to current research and development (R&D) spending commitments set out in the 2020 Budget, including providing guarantees for third country participation in Horizon Europe. A national replacement mobility scheme should also be fully funded.

- Ensure that the UK’s visa and immigration system offers a ‘best-in-class’ service to international talent in terms of cost, accessibility and ease of navigation

- See other recommendations listed on pages 13-14

- Health and well-being

- Secure the sustained growth of healthcare programmes to meet the government’s ambitious targets through funded expansion of medical and health/social care placements and investment in teaching capacity, including support for digital innovation and simulation.

- Commit support for clinical academic roles and career pathways that provide teaching and research capacity, and instil research-informed practice that is shown by evidence to improve patient outcomes, quality and safety.

- Target support for whole-university approaches to the mental health and well-being of students and staff to build on the lifetime well-being gain for graduates, enhancing their resilience and health literacy.

- Tackling climate change – see page 18

- Culture and community – Support our creative economy by reviewing R&D definitions to ensure that these are not narrower than those of competitors, and do not neglect R&D in the UK’s internationally strong creative industries, which have been hit hard by Covid-19 measures.

Research news

The Minister writes: Amanda Solloway has written to Greg Clark (Chair of the Science and Technology Committee) on the stages of consultation and discussion the Government has taken in the development of the new ARPA style body. She also responded to the Committee’s questions on university research funding and Horizon Europe and alternatives.

Reforming the REF

Amanda Solloway spoke of reforming the REF in the Research Landscape speech for the Education Policy Institute webinar on Tuesday.

She said that the Government recognises the importance of science and innovation for the future and mentioned the commitment to increase public spending on R&D to £22 billion per year by 2024/25. On the Roadmap she said there was a duty to spend that money wisely so it can make the biggest difference possible. Key to this is evaluation… And evaluation can be a powerful incentive – and it can change behaviours. Through linking evaluation to funding, we have introduced policies intended to drive greater impact and openness from our research… But, if implemented in the wrong way, or in a way which doesn’t evolve, evaluation can drive negative behaviours. She said culture was at the root of the challenges with conducting research.

Key points:

- Researchers tell me they feel pressure to publish in particular venues in order to gain the respect of their peers, which wrongly suggests that where you publish something is more important than what you say. That just can’t be right.

- People talk to me about “REF-able publications” – a total distortion of the value of research and a constraint on the diversity of research objectives. Despite the rich variety of outputs that can come from research, over 97% of outputs submitted to REF 2014 were text-based. Just think about that. And it is surprising how commonplace it is to talk about the UK’s leading position in “citation impact” – an odd phrase, actually, which confuses a process with an outcome. Indeed, the processes researchers use to communicate with each other have now become so ingrained into the recognition and reward system that publication and citation seem to have become ends in themselves…. people feel pressured to show significant results from their work, to get it published, just to justify the effort and investment involved…This could be having a profound effect on the very integrity of science itself – leading to questionable research practices and evidence of a growing crisis in the reproducibility of research.

- We have created this situation, in part because of the way we evaluate success.

- Although intended for simple purposes, universities have turned the REF into a major industry, with rising costs and complexity. Lord Stern also commented on this, but I am not convinced that the changes introduced have gone far enough. There are now very few parts of academic life in the UK that are not affected in some way by the REF.

- …a risk-averse compliance culture risks stifling creativity and diversity.

- … we know that 4 in 10 surveyed researchers believe that their workplace puts more value on metrics than on research quality.

- …it’s really important that I say clearly up front. I have absolutely no intention of disrupting the important work of the current REF. It is vital that this work continue as planned, delivering robust outcomes which will inform significant funding decisions over the coming years. And, perhaps even more importantly, we must protect our dual support system, which is a key strategic advantage for the UK research base.

- However, we must be prepared to look to the future and ask ourselves how the REF can be evolved for the better, so that universities and funders work together to help build the research culture we all aspire to. We need to work together to build an evaluation system that achieves our goals.

- More quality time spent on research.

- A positive culture which recognises all contributions to research.

- A culture which motivates people to do diverse, creative and risk-taking work.

- Institutions improving in ways that align to their diverse missions.

- And clear accountability for public funding without layer upon layer of complex bureaucracy.

- We should not shy away from asking the tough questions.

- We need to be prepared to take bold decisions.

- We need to consult widely… Culture change doesn’t happen overnight – and this is equally a conversation which we must not rush. I have today written to Research England to ask them to start working with their counterparts in the devolved administrations on a plan for reforming the REF after the current exercise is complete. Recognising the importance of protecting the current REF and valuing it. But being clear that we need to continue the journey towards building that better system we need.

Research Professional cover the speech here and Wonkhe pick apart the speech in a very short (and worthwhile) blog, read the comments too!

REF2021 – Research Professional have a piece on getting REF 20201 ‘done’.

Horizon Europe – Politico raises concerns of ‘long-term consequences’ if UK does not participate in Horizon Europe following a leaked scientist letter.

Funding News – Wonkhe tell us:

- The Wellcome Trust has launched a new vision and strategy for the research they fund. Wellcome’s current funding schemes will close over the course of 2021, to be replaced by three new discovery research schemes. These will cover work done in the fields of mental health, global warming, and infectious disease. The exact closing date for specific schemes can be found on Wellcome’s website. Applications for the new schemes will open in summer 2021.

- UKRI has announced details of support and facilities available to Natural Environment Research Council grant holders. This consists of specialised equipment, analytical facilities, and expert advice for researchers.

Race Equality: Advance HE have a short video by PhD student Daniel Akinbosede on race equality and why it is important for HE to mark black history month. He covers the research funding awarding gaps and he urges HE institutions to use Black History month to reassess their policies and processes rather than ‘just hosting a few cultural events’.

Prolific Publishing : Times Higher profile a gambling studies academic who publishes a paper every two days

EU / UK Research & Education: You can watch a session on the future UK-EU relationship on research and education. The Committee intends to address these questions during the session:

- Should the UK seek third country affiliation with the EU’s Horizon Europe and Erasmus+ programmes at the end of the transition period?

- What should the priorities be for future domestic research funding if the UK does not affiliate with Horizon Europe?

- How might the lack of a positive data adequacy decision at the end of the transition period affect the UK’s research and education sector?

- What would the impact of a ‘no agreement’ scenario be for UK universities and research bodies?

- Are research and education organisations, including universities, research institutes and businesses, well prepared for a ‘no agreement’ scenario at the end of the transition period?

Answering the Committee’s questions will be:

- Professor Sir Richard Catlow, Foreign Secretary and Vice President, Royal Society

- Catherine Guinard, Policy and Advocacy Manager, Wellcome Trust

- Hillary Gyebi-Ababio, Vice President for Higher Education, National Union of Students

- Vivienne Stern, Director, Universities UK International.

Parliamentary Question: how much funding the Government plans to make available in grants during the second stage of the university covid-19 research support package that was announced in June 2020. Amanda Solloway answered: …it will depend on income losses which at this point remain unclear – each university’s allocation is the lower of 80% of losses in international student income or the value of non-public research funding.

Future International Research Partnerships: UUK published Future international partnerships: putting the UK at the heart of global research and innovation collaboration. They state it

- …proposes a wide-ranging set of policy recommendations to enable UK universities to grow and diversify their international research and innovation collaborations. Specifically it sets out a clear plan for how the UK can expand and capitalise on researchers’ international links to attract talent and business investment from overseas.

- Over the next decade, universities will pull their weight to ensure that the UK is able to meet global, national, regional and local needs…Universities…will be instrumental to make the government’s vision a reality through their international networks of excellent partners (Chapter 2) , their critical contribution to building innovation capacity in their local economy (Chapter 3) and their institutional partnerships with universities across the world (Chapter 4) provided that their role as global collaborators becomes a feature of the domestic system in the future (Chapter 1).

- … However, this requires taking a strategic system view in which international connections are hardwired into the structure of the domestic funding system, rather than treated as an add-on or an afterthought

Recommendations for each area are peppered throughout the text and cover responsibilities for both Government and HE institutions.

Scottish Shake Up

Wonkhe succinctly report on a FE/HE review commencing in Scotland:

- The first phase of what amounts to a major Scottish Funding Council review of the shape and scope of the HE and FE sectors hints at a unified funding model by level of provision, and a range of potential collaborations. The report – “Coherence and sustainability: a review of Scotland’s colleges and universities: phase one” – focuses on the “emergency period” of 2020-22, but recommendations are made with an ear to existing trends and likely future societal needs.

- An associated financial projection highlights the varied impact of Covid-19 on sector providers. The report suggests a number of potential measures – including a cut in student numbers, consolidation of courses across providers, and “fee-only” places for providers that can afford to take the loss. Of interest around the UK will be potential measures to include regional demographic and economic skill demand data in planning and funding higher education. This first stage report follows a period of consultation with stakeholders – further such consultation will take place before the phase two report is released in February 2021.

- The Times has an opinion piece from Anton Muscatelli, Principal of the University of Glasgow, which welcomes the review and calls on the universities of Scotland to work together.

And a blog: A Scottish Funding Council review is supportive of the sector as it stands, but ambitious in rethinking tertiary education post-Covid.

Petitions

Parliament’s Petitions Committee considers all e-petitions which achieve over 10,000 signatures. Decisions on all are here. Of most interest are:

Modular learning

UUK have published a summary of results from a poll they commissioned with English adults aged 18-60 who were interested in future university study and either unemployed (or at risk) or wanting to up or re skill.

- 82% were keen to study individual modules of a degree and this would make them more likely to undertake university study. (Currently learners have to commit to 25% of full time equivalent to access financial support/loans.)

- Earning whilst learning and maintaining a good work-life balance were important and the top benefits identified for modular learning.

UUK say these findings come as universities call for the introduction of loans for more flexible study, which would unlock opportunities for those with caring or work responsibilities.

- Business management was the most popular subject individuals would select; engineering was second (a skills shortage area in industry), then teaching and nursing/allied healthcare

- 13% who were interested in university education said they were not likely to study part-time, but would consider modular study. UUK say this finding means that modular study has the potential to increase the number of people with high level skills in the UK

- 93% of those likely to undertake modular study, if loans were introduced, placed value on being able to gradually build up to a full qualification

- Over one third of those unlikely to undertake modular study, even if loans were introduced, were concerned about repayment.

UUK say: The polling also revealed concerns over how financially accessible university study is, highlighting the need for a comprehensive government-funded national education campaign on student finance… The lack of clear information on the student finance system is holding back individuals of all ages that could benefit from higher education. Targeted maintenance support should also be explored to ensure flexible learning opportunities are truly open to everyone who would benefit.

UUK Chief Executive, Alistair Jarvis, said:

- With one million more job losses forecast by the end of the year, it is more important than ever to boost people’s skills and maximise their job prospects in a flexible way.

- The government should change the eligibility criteria for financial support for higher education to allow more people to benefit from access to shorter courses, and it should make information about the student finance system more accessible.

- The recent announcement of a Lifetime Skills Guarantee is welcome, but it is not yet clear how much flexibility will be built into the system at undergraduate and postgraduate level.

- Providing more people with the opportunity to upskill and retrain will be crucial to meeting the country’s skills needs, rebuilding the economy and levelling up.

Growth of HE by 2035

HEPI have published Demand for Higher Education to 2035 which considers the country’s changing demographics and participation rates. It finds that England will need an additional 350,000 more places, whilst Scotland will need fewer places despite increased participation in HE.

The report explains the findings:

In England –

- if demography were the only factor, without any increase in participation, there would be an increase in demand of 40,000 full-time higher education places in England by 2035 due to rises in the 18-year old population;

- if participation also increases in the next fifteen years at the same rate as the average of the last ten years, then this increases to a demand of 358,000 full time higher education places by 2035;

- the greatest growth in demand will be seen in London and the South East, due to both demographic changes and patterns of participation. Our projections suggest that over 40% of demand for places will be in London and the South East.

In Scotland –

- if demography were the only factor, without any increase in participation, there would be a decrease in demand of 18,000 full-time higher education places in Scotland by 2035 due to a decline in the 18-year old population;

- if participation also increases in the next fifteen years at the same rate as the average of the last five years, then we can expect the decrease in demand to shrink to close to nil full-time higher education places by 2035;

- these projections suggest Scotland will be able to accommodate a growth of participation in higher education without increasing student numbers, due to a decline in the 18-year old population.

This is ambivalent news for Scotland who are already struggling with the financial effects of Covid and the impact on their HE institutions. However, whilst expansion seems unlikely it means the cost to the Scottish Government is less. Wales isn’t covered by the report and Northern Ireland is expected to be similar to Scotland but precise calculations are not possible because of data comparisons would be inaccurate.

Although the report does cover how some in Government would like the student numbers cap on HE places to return it doesn’t really tackle the effect of the Government’s intention for technical education demand to increase, with a likely resulting shrinkage in traditional HE degree route. Although written for another topic Sarah likes the below by Wonkhe which summarises the Government direction:

- Developing government rhetoric on “low-value” or “low-quality” courses in higher education seems to be evolving to address a concern that too many students do not progress into graduate jobs when they take those courses. The hope seems to be that creating more technical routes at levels four and five and – potentially – reducing the availability of degree-level courses that might cannibalise demand for these new routes will funnel at least some of those students in a more economically productive direction, as well as create new education opportunities for those who are less likely to progress to degree-level higher education…white working class young people…

Research Professional also make interesting comments in the same vein:

- Previous incarnations of the Conservative government imagined that a growing demand for higher education in England would be met by the private sector. That was the whole point of the Higher Education and Research Act 2017, which sought to create favourable conditions for supply-side reform in higher education. That spirit seems to have been abandoned… The Johnson-Cummings-Williamson way seems to be to funnel that demand into further and technical education… the government is… listening to its skills tsar Alison Wolf. Wolf is a devotee of the eccentric notion that the UK’s productivity problem is the result of too many graduates working in non-graduate jobs, and that the cure is to boost the number of people with subdegree technical qualifications. Of course, the increased demand for higher education that Hepi identifies does not necessarily translate into a corresponding rise in graduate job opportunities, but it does reflect a competitive dynamic in the workforce whereby higher education is the perceived path to successful employment.

- Wolf’s emphasis on technical education will not address the country’s productivity woes. It may, however, go some way to addressing the UK’s reliance on immigrant labour to fill technical vacancies in the labour market. The two things should not be confused.

- UK productivity issues are not caused by its higher education participation rates but by the massive imbalance in the UK economy between services and manufacturing, the uncompetitiveness of sterling against currencies in emerging economies, and being slow out of the gates on the fourth industrial revolution. None of which can be solved by sending fewer people to university.

Returning back to the HEPI report…

However, while FE intentions and the growth of technical alternatives may direct young people aware from the traditional academic degree the HEPI report highlights how we are entering a global recession and that student numbers tend to increase during a recession as people choose to avoid entering an unstable labour market or look to retrain. On page 40 of the report HEPI also ponder a growth in mature numbers (again due to need to retrain and the intended flexibility in the loan system) and page 41 looks at the impact of Level 3 attainment increases and decreases on HE admissions. HEPI conclude that the growth in demand for English HE

- should not make the higher education sector complacent. All these projections could be over-estimations if government policy were to change to restrict the number of students entering higher education. Assuming there is no significant change to the student loan charges and repayment terms, the projections set out in this report will be seen as a significant additional cost to the Government. The response to this could be to limit the overall numbers of students entering higher education by setting student number caps, limiting the provision of courses that are deemed ‘low value’ or by introducing minimum entry standards. All of these would limit the number of people able to enter higher education. It is likely that the effects of any of these changes would be felt most by those students from disadvantaged backgrounds. If we want to see all those who www.hepi.ac.uk 45 wish to enter higher education able to do so, we will need to continue to make the case to Government of why, now more than ever, continuing to educate our population to higher levels is so critical.

Rachel Hewitt, HEPI Director of Policy and Advocacy, said:

- There have been declining numbers of 18-year olds in the population in recent years, which has impacted the way universities have operated. However, 2020 is the last year of this trend and universities are set to see a significant rise in student numbers over the next fifteen years. Among focusing on their recovery from the current pandemic, universities will need to consider how they can scale up to incorporate this level of demand. Government will also need to consider how to best prepare for this increased level of demand.

- There are those who would like to see a cap on the number of students entering higher education. However, these projections show clearly that if trends in participation continue as in recent years, capping student numbers in England would deprive a growing group of students who will be looking to enter higher education, which would likely be detrimental to the push for greater equality of access to higher education.

- Our projections suggest the greatest growth is likely to be seen in London and the South East, partly due to their existing higher levels of participation. If government is committed to levelling up across the country, perhaps the focus should be on the disparity of participation rates across England, rather than debating national targets.

- For policymakers in Scotland, these projections suggest an easier path to tread…Scottish universities should be able to take on more students without having to expand the number of places available, limiting the cost to the Scottish Government.

Research Professional have their take on the HEPI report here.

Covid news

While the discussion of how to get students home for Christmas still hasn’t abated this weekend the media are asking whether – once the majority are back home – how feasible it is for students to return to campus in January. Guardian article here; BBC here.

Research Professional:…what happens when they all need to head back to their university campuses again. Can Covid Britain condone not one but two mass movements of people in the space of less than a month? We are already witnessing the fallout from just one student exodus

From the BBC article:

- …options are under discussion about whether next term should be fully online – or maybe for the initial weeks – or for delayed or staggered starts, rather than risking triggering a fresh wave of campus outbreaks.

- Students could “amplify” the spread of coronavirus, said the SAGE advice, and movement around the Christmas holidays posed “a significant risk to both extended families and local communities”.

- Unlike the autumn term – when university starting dates in the UK are spread across about a month – the January return is much more concentrated. And it leaves the universities and the government with a decision about whether to press ahead with bringing students home and then straight back again, including across areas where travel is being discouraged – or finding a different way of starting the new term.

- university leaders are pointing to the idea of a greatly expanded testing regime – and say privately that campus outbreaks seem to have peaked and are subsiding.

The BBC article also states decisions on the process for students who wish to return home for Christmas will be published next week (commencing 26 October). Among the issues to be clarified will be how, if in-person teaching stops in the week beginning 7 December, what would stop students disappearing home in the days before that, rather than remain confined for a fortnight’s isolation. They’re adults and it isn’t boarding school. The DfE is expected to publish a specific date that face to face tuition should cease by.

And whether students will even want to return is covered by the Guardian:

- The growing fear, meanwhile, is that disillusioned students may simply drop out – a decision with consequences for the rest of their lives. Some struggling freshers have already fled, while others have quietly started commuting from home. Academics still teaching in person talk of lecture theatres emptying out, with students either self-isolating or too frightened to show up.

- Boris Johnson has vowed to get students safely home for Christmas, but some in academia are beginning to worry more about getting them back in January. What if some decide they’d rather not risk getting trapped in locked-down cities once again? Before long, the government may be forced once again to choose between pumping more cash into universities or trying to craft a solution on the cheap. Let’s hope this time it doesn’t fail the test.

Wales: Welsh universities will continue to deliver blended learning during the two week fire-break lockdown. It has been stated that it is safer for students to remain on campus during the firebreak and to avoid travelling home.

Covid Cases: Wonkhe have a very short analysis.

- It states: This…is not an absolutely reliable indicator – but it does look like the days of extremely rapidly growing case numbers among students might be behind us…Universities have been particularly good at testing, and fairly good at managing student self-isolation…What we don’t know…is the number of symptomatic cases, or the severity of those cases.

- None of this is to downplay the huge number of cases in student-heavy MSOAs, or the utter foolishness of bring students back to campus this term. We need to think about next term very carefully…We are by no means leaving the second wave, though the student-based initial spike may be coming to an end.

The Times also reports a slow down in young case numbers.

Covid related parliamentary questions

Student Complaints

The Welsh move has reinvigorated media debate concerning whether all HE teaching should be online or face to face continue where it is essential. We’ve all been around this discussion wheel many times now. Research Professional bring it up again and highlight that an (unnamed) Vice Chancellor has sensibly said [That] there were three main reasons to keep in-person teaching going:

- universities have worked hard to make campuses and classrooms Covid-secure;

- depriving students of face-to-face teaching could exacerbate mental health problems; and

- putting all teaching online could lead to the risk of students moving around the country and spreading the virus.

And Research Professional (RP) add (you’re allowed to sigh here): A fourth consideration not mentioned by the vice-chancellor could be the need to deliver what was advertised and avoid complaints—and more calls for tuition fee refunds. They mention the new OfS intention to monitor universities with significant numbers of students being required to take all their courses online and the pre-pandemic strike action.

In addition, RP made freedom of information requests to research-intensive universities finding that during lockdown the number of complaints about teaching or course…grew in 2020 compared with the same period in 2019. RP continues: At King’s College London, for example, complaints rocketed from 17 in 2019 to 567 in 2020. Cardiff’s response to the FOI request sums it up: the past two years had been “some of the most difficult for our students and their university experience”. While the spokesperson pointed out that the “vast majority” of Cardiff’s 30,000 students had not complained, the university recognised that there had been a “disappointing” increase in complaints… The cumulative impact of two periods of industrial action on some, and the current global pandemic, have presented unprecedented challenges and impacted on the delivery of teaching and learning.

What is interesting to note is that quite a volume of complaints relate to the strikes rather than the vast majority on Covid related online teaching and learning, as the media would have us believe. And RP highlight that Not all universities that responded to our request reported a rise in complaints, and not all complaints will translate into requests for tuition fee refunds. Anyone who has ever written an online review knows that the act of complaining can be cathartic enough. If you have the will you can read more from RP on complaints here.

The Guardian have an article too capturing the student voice amongst the reporting.

Research Professional highlight the parental role in student complaints:

- Beware, too, the wrath of the helicopter parent.

- “In Facebook groups and WhatsApp circles, parents furious that their children are racking up debt in order to be banged up in Covid-riddled halls of residence are beginning to organise,” Hinsliff wrote in her Guardian op-ed. “One group of parents, using the hashtag #Fees4What, has started an online petition urging parity with Scotland, where students have the right to end university tenancy agreements early owing to Covid; others are plotting legal challenges.”

- Playbook has followed the threat of mass student actions closely, as you will know. We have spent less time considering the possibility of parents and guardians mobilising to bring legal action against a provider. It is a scary thought.

Smita Jamdar writes for Research Professional to suggest how universities can mitigate the risk of student demands for refunds. Smita writes:

- routes are available to students to secure what are, in effect, partial or full refunds—but to do so, they would have to identify specific assurances and promises made by institutions that had not been fulfilled, or alternatively show that the service they received was not of a reasonable standard.

Smita suggests that To mitigate the risk of claims universities can:

- Ensure that information for students and prospective students is accurate and up to date

- Changes to provision and services should be kept under review to ensure that wherever possible, the impact on students is continually monitored and appropriate remedial action is taken as promptly as possible. Particular attention should be paid to those courses and students where the risk of adverse impact is especially high: practical and laboratory-based courses and students with disabilities, for example. Communication of changes needs to be accurate, clear and regular.

- Universities should comply with the provisions of any force majeure clause carefully. There may be obligations to give notice or to consult students that must be discharged or the clause may not be enforceable.

- Low-level complaints and social media storms can be useful indicators of where future legal claims may lie, and institutions should ensure that quick action can be taken in response to emerging problems. It may be helpful to have an escalation process that ensures problem areas within specific schools and faculties are logged at a central point, which considers whether there are lessons for the wider institution.

- introducing a bespoke, simplified complaints process, so that every effort can be made to address complaints without the need for external consideration…This should be accompanied by clear guidance for decision-makers so that there is a consistent position across complaints, and consistency of findings and outcomes, without the different facts and circumstances of each case being overlooked.

Wonkhe have a guest blog on fee refunds urging universities to explain things better.

Access & Participation

White Working Class: Following last week’s NEON publication Wonkhe have a blog on not treating white working class as a homogenous group.

- …exactly who are we talking about? Are we all talking about the same group when we discuss the white working class?

- Any comparison between ethnic groups has to grapple with the fact that the white working class far outnumbers any other ethnic group. And they live all over the country, from deprived fishing villages in Devon, rusting seaside resorts on the Essex coast, former pit villages in Cumbria, and on council estates in Toxteth, Kilmarnock, Aberdare, or Romford.

- These structural questions, about who lives where, with what infrastructure, and what opportunities, these are the things that come to mind when I think about what my chances of getting in higher education were.

- I have no doubt that most who use the term mean well, just as I know that there are many people across the UK who find that the term suits them well. But if we’re going to solve the issue of so few white working class boys and girls entering higher education, then we need to be more precise and engage with the country as it exists.

- Britain is still a country shaped by wealth and class. The way we start to fix that is by looking seriously at how working class people actually live, and that begins by talking to us, not just about us.

There is a great comment to the blog which highlights that the past measures of social class were withdrawn and there hasn’t been a replacement:

- A big issue is that there is virtually no official data on social class collected and reported on meaning that we are stuck with poor proxies such as free school meal eligibility or living in a disadvantaged area. The first narrows the debate a lot – it confuses being from a working-class background with being in poverty and so only includes a sub-set of people from working-class backgrounds. The second captures a lot of people from advantaged backgrounds and, for POLAR and similar measures, ignores ethnically diverse working-class areas including (virtually) the whole of London and large parts of other cities.

- HE data by social class used to [be] reported until HEFCE decided to abolish it a few years ago despite the pleas of the Social Mobility Commission on the basis that data quality was poor (I think it’s still collected though – just not available publicly). The planned replacement measures appear to have been canned, meaning we’re left with two measures of disadvantage, neither of which are good proxies of coming from a working-class background: going to a state school and living in POLAR/TUNDRA Q1…

- This lack of data needs to be resolved…[if] the UK Government wants to get serious about tackling the inequalities faced by those from white working-class backgrounds. Enacting Section 1 of the Equalities Act 2010 to impose a duty on public bodies to “when making decisions of a strategic nature about how to exercise its functions, have due regard to the desirability of exercising them in a way that is designed to reduce the inequalities of outcome which result from socio-economic disadvantage” would also help – it’s been lying around on the statute book for over a decade now…

Recycling spending again and again: Wonkhe have a blog – Jim Dickinson took to Wonk Corner yesterday to count the number of times that DfE has reallocated £256m of Student Premium Funding since the start of the pandemic. It’s a lot.

Education: Equality of Opportunity: An oral question within the Commons on ensuring equality of opportunity in education took place this week.

Michelle Donelan (Universities Minister): … talent is equally distributed, but opportunity is not. This Government have made it our mission to rectify that, and equality of opportunity lies at the heart of the work by the Department for Education, including opportunity areas, access to higher education work and reforms to further education such as the flagship T-levels. We recognise that education has an unparalleled ability to create and unlock opportunities across the nation.

White working class, the levelling up agenda, and raising school standards were also mentioned.

Parliamentary Questions

Gaps: Advance HE have published their annual analysis of students by equalities characteristics LINK. Wonkhe have a blog by Advance HE introducing the key points. Numbers of students with declared disabilities have more than doubled since 2003-04, and the participation gap between the genders continues to increase. The blog also highlights that at the current rate of progress the awarding gap between white and BAME students would not close until 2070-71, and that between white and black students until 2085-86.

SEN: A parliamentary question on when the Government expect to publish the outcome of their review of support for children with special educational needs and disabilities. The answer should pop up on this link from 3 November onwards.

Non-continuation

There has been speculation whether the difficult study circumstances in 2020/21 will lead to an increase in the student drop out rate. Students who leave university within (roughly) four weeks of first commencing are not liable for their tuition fee loan. This week Wonkhe have been talking about the official measures – the Higher Education Statistics Agency’s UK Performance Indicator on non-continuation – which captures data on students who leave more than 50 days after the start of their course (but not before). This leaves a hole round about days 28-50 where student drop out is not monitored nationally. Wonkhe state:

- So even in three years’ time, when this data is released, we will never know exactly what happened at the start of the autumn 2020 term. Another unknown and unknowable number is of the students who enrolled and never turned up, or that left within two weeks…In 2020, an empty room in a hall or an unanswered Zoom call might be the only indication that something has gone wrong.

Wonkhe have a blog cobbling together a data source to show attrition. On non-continuation they highlight that it is often a drawn out withdrawal:

- When a student “leaves” higher education they tend not to make a sudden decision and then immediately notify everyone that needs to know. The process is best understood as a gradual disengagement. A student may stop attending lectures first of all, or find themselves unable to continue to support themselves financially, or find themselves with other responsibilities and other constraints that stop them being able to participate.

International & Mobility

The DfE updated guidance on UK students intending to study in the EU after the transition period. The information relates to those who are planning to study in the EU, and those who are continuing their studies in the EU. The links also contain information on travel insurance, making changes to Erasmus+ placements and support when students are abroad.

Exceptional Circumstances

SUMS Consulting published a short briefing paper: Crystal Ball Gazing: What is the Future for Handling Exceptional Circumstances? Highlighting the changes that were made to exceptional circumstance policies to account for the pandemic disruption but also addressing the exponential increase in the volume of requests for exceptional circumstances in recent years. There is more content here. The paper concludes:

- The combination of Covid-19 and the learnings from the last few months have led many universities to significantly change their approach to exceptional circumstances. Over the next few months, it is inevitable that further adaptions may be required to accommodate events such as local lockdowns or students being sent home. There is a move to divert resources from approaches that add little value, to those that benefit the student. Universities are adapting their evidence requirements, introducing self-certification and focusing on consistency across academic disciplines. The OIA is due to publish the final version its Good Practice Framework later this year, and there is no doubt that this too will incorporate many of the lessons from universities in operating the process during Covid-19. The pandemic has accelerated the rate of change in so many aspects of university life – the exceptional circumstances process is proving to be no different.

- In thinking about their exceptional circumstances process this year, universities may wish to consider:

- How coherent is your overall policy framework? When were related policies last updated?

- How recently have you reviewed the evidence required to support exceptional circumstances?

- How recently have you reviewed the list of examples of circumstances that are likely to be accepted and those that are likely to be excluded?

- How do you ensure that there is consistency and equity in determining exceptional circumstances across different disciplines and academic units?

- Have you decided whether to introduce self-certification with safeguards, if you have not already taken this step?

- Analysing your data over an academic year in the way that UWE has done, to discover the impact of your present process.

- Whether or not your existing processes are inclusive?

Young unemployment

The Alliance for Full Employment (AFFE) have published Youth Report: A Million Reasons to Act on the impact of the pandemic on young people’s employment prospects. Under-25s suffered 60% of the post-March redundancies, and male youth unemployment is at 16%, more than three times the UK adult rate. They call on the Government to convene a jobs summit of UK nations and regions to address to impending issue.

The report also states that Kickstart, the Government’s main youth unemployment programme, will not provide anywhere near enough places for those in need of support. The report estimates that over 1m young people will be unemployed by November, and are likely to “fall through the net.”

They identify four new groups who will require the Government’s attention and help as we head into winter:

- Many of this summer’s 500,000 school college and university leavers

- Young people who lose their jobs on or before October 31as a result of Covid, as furlough ends

- Young people in partial lockdown areas where businesses are closed down and where young employees not eligible for furlough are being laid off

- Young people made unemployed because of the general turnover of staff, which is highest among the young, and including those on temporary contracts, who will now struggle to get new opportunities.

The report, which features a foreword by former PM Gordon Brown, recommends the following priorities for the Government:

- Provision of quality work experience – not a return to the Youth Opportunity Programmes (YOPs) or Youth Training Schemes of the 1980s

- Training geared to new jobs, like in care sector It and logistics, jobs linked to the recovery from lab technicians and contact tracers, to care worker and teaching assistant not training for continued unemployment.

- Help with job searches – a vital element of getting into work, as demonstrated by the 2009 Future Jobs Fund.

- A wage subsidy in the order of a £100 a week for six months for employers to take a young person on full-time.

Prof. Gregg (author) concludes: The recession in the UK has only just started, in terms of the impact on jobs, consumer confidence and firm planning. Yet because firm profitability was already low and the trading block under Lockdown, the wave of job losses will be incredibly condensed and intense between now and next April. This means that the need for getting intervention on the ground is urgent and hard to get to scale in time.

The Guardian cover the above report and report on a call from former PM Gordon Brown for employers to be given a wage subsidy of £100 a week to hire workers under 25 as part of a plan to prevent youth unemployment exceeding levels seen in the 1980s.

Graduate unemployment was also mentioned in this week’s Department for Work and Pensions topical questions:

Q- Tim Loughton (Con): With forecasts showing that there may be as many as 1 million young people without a job, I urge the Minister to think outside the box. I have long argued that we should use graduates and gap-year students to help some of those pupils who have missed out on schooling to catch up. Can we devise, with the Department for Education, a scheme to pay them a variation of JSA to provide such a service, or at least offer greater flexibility for claimants who volunteer to help in such a way or to take the pressure off other public services?

A – Dr Coffey: One element of the kickstart scheme, a £2 billion investment in the future of our young people, is designed to help people to get on the first rung of the ladder with a proper job. It is a way for those people who have recently left school or university and are at risk of long-term unemployment to get experience and financing, which does not just have to be through private organisations and could be through local government or charitable or other sectors. It is a specific way to ensure that those people get not only a job but the extra training and wraparound support that they need to help them further on in their lives.

PQs

As we’re on a break next week some of the parliamentary questions cover the two week period, you may have to check back on them in early November to see the response.

HE sector

Inquiries and Consultations

Click here to view the updated inquiries and consultation tracker. Email us on policy@bournemouth.ac.uk if you’d like to contribute to any of the current consultations.

Other news

Shadow Education Secretary – Kate Green has been in post as the Shadow Education Secretary for 3 months already. There is a good background and profile on her in Schools Week which suggests she is committed to slower policy making with sufficient time for research and evidence based formulation.

Historic Statues: Colleagues following the debate surrounding the removal of historic statues may be interested in this Lords discussion on the topic. It is not specifically HE or education focussed, although the matters covered do have some application.

Groceries: While it isn’t policy news, if you were interested in the reasons behind the price increases for your food shopping during lockdown the Institute for Fiscal Studies have a paper on it. In short: less promotions were available and there was a reduction in product variety. They’re unsure if the autumn restrictions will see the return of grocery inflation.

HE numbers: The House of Commons Library has published a research briefing on HE numbers. It finds that: Headline student numbers have increased to new records following a short dip after to the 2012 reforms. There are however ongoing concerns about numbers outside this group where trends have not been so positive, including part-time undergraduates, some postgraduates students, overseas students from some countries, especially Nigeria and Malaysia, mature students and some disadvantaged groups. There is also considerable concern about the impact of the coronavirus pandemic and student numbers, particularly those from overseas and uncertainty about the impact of Brexit on EU student numbers.

Physics: The Institute of Physics is railing against the limiting words of others which are influencing young people from continuing to study physics post-16. Report here.

- many young people who want to pursue physics to improve their future are being denied the opportunity by those whose opinions they trust.

- many young people are put off studying physics from age 16 by misconceptions about what physics is

- They are told “physics is too difficult”, “it’s not creative” or “it’s boring”… They are told that physics is not for the likes of them based on their ethnicity, their sexual orientation, their disability and their social background.

- People of Black Caribbean descent: In England, young people of Black Caribbean descent represent the ethnic group least likely to pursue physics post-16, with only 0.5% choosing to study physics A-Level despite making up 1.4% of all young people in England aged 16 – 19.

- People from poorer backgrounds: Young people from poorer backgrounds are much less likely to study physics than peers from wealthier backgrounds. In England, only 2.7% of students from the most deprived backgrounds choose physics post-16 compared to 8.1% of the least deprived.

- Girls: Latest figures show that girls are far less likely than boys to choose to study physics post-16. In 2020, physics was the second most popular A-level subject for boys in England and Wales and the fifth most popular in Northern Ireland. In 2019, only 3.59% (1,869) of girls in the Republic of Ireland chose Leaving Certificate physics, compared to 9.91% (5,884) of boys.

- People with disabilities: According to the Higher Education Statistics Agency, in 2017/18, 13% of physics undergraduates in the UK had a known disability, much lower than the percentage for all working age adults (19%).

Recess

The House of Commons enters recess next week and the policy update will take a break. We’ll be back on 6 November.

Subscribe!

To subscribe to the weekly policy update simply email policy@bournemouth.ac.uk. A BU email address is required to subscribe.

External readers: Thank you to our external readers who enjoy our policy updates. Not all our content is accessible to external readers, but you can continue to read our updates which omit the restricted content on the policy pages of the BU Research Blog – here’s the link.

Did you know? You can catch up on previous versions of the policy update on BU’s intranet pages here. Some links require access to a BU account- BU staff not able to click through to an external link should contact eresourceshelp@bournemouth.ac.uk for further assistance.

JANE FORSTER | SARAH CARTER

Policy Advisor Policy & Public Affairs Officer

Follow: @PolicyBU on Twitter | policy@bournemouth.ac.uk

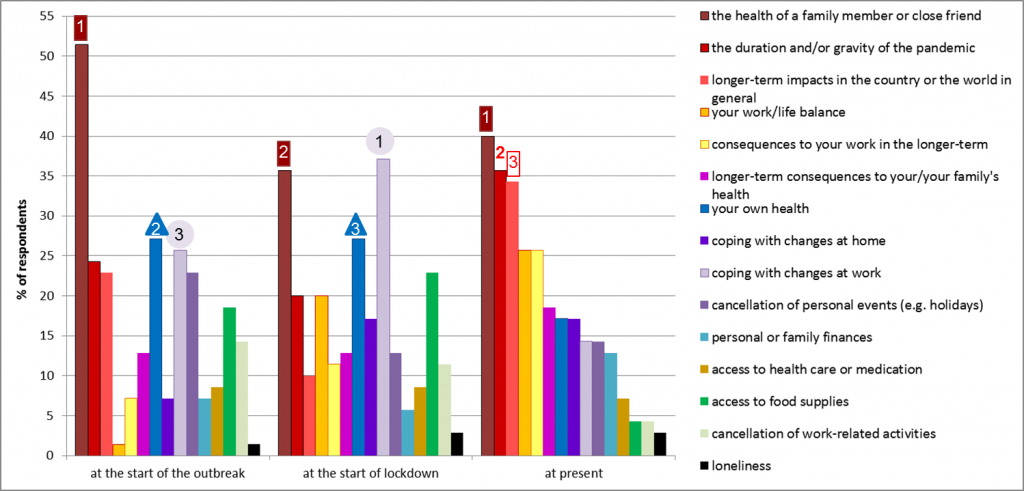

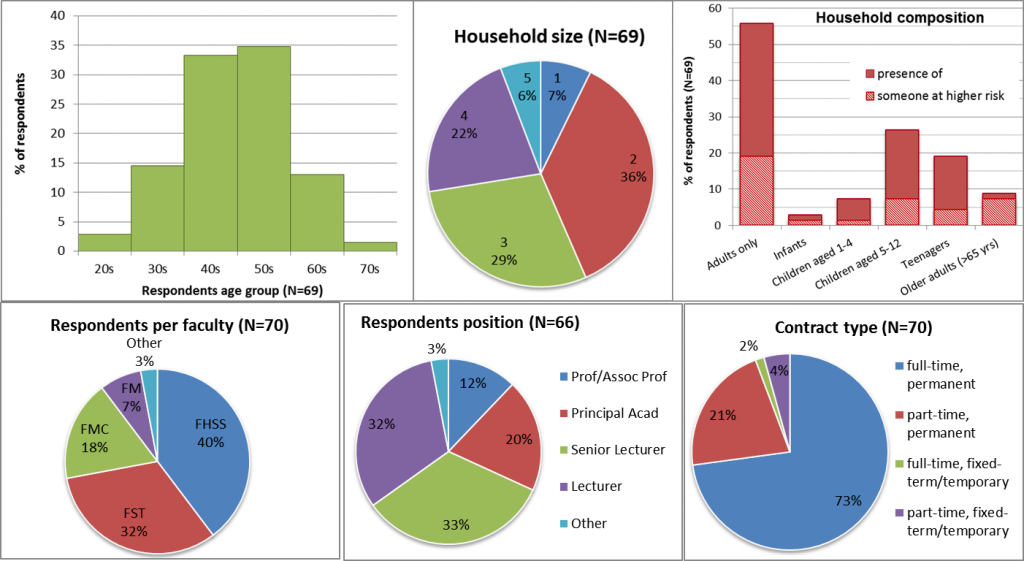

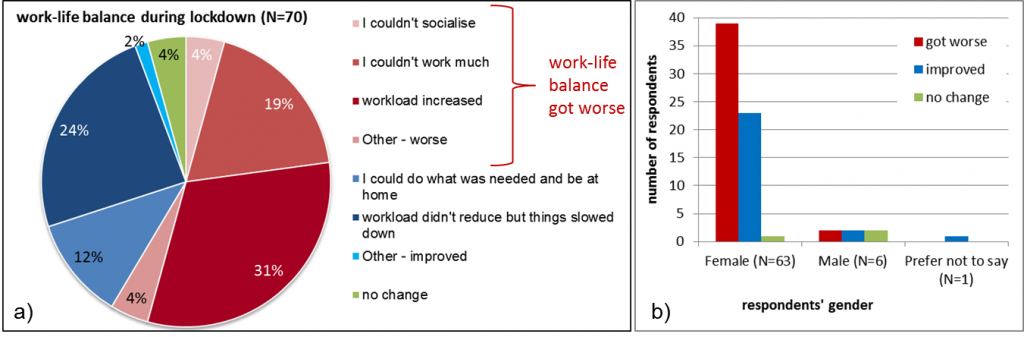

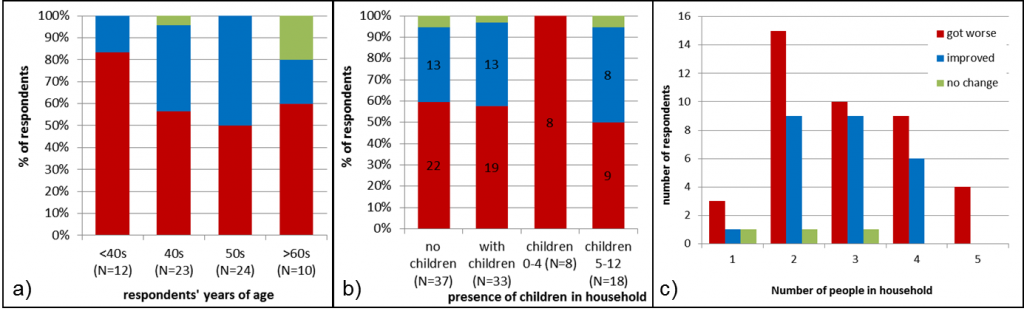

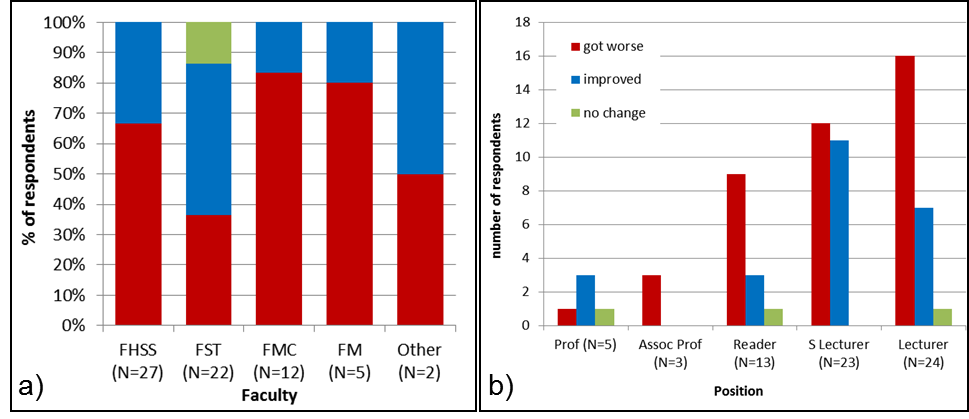

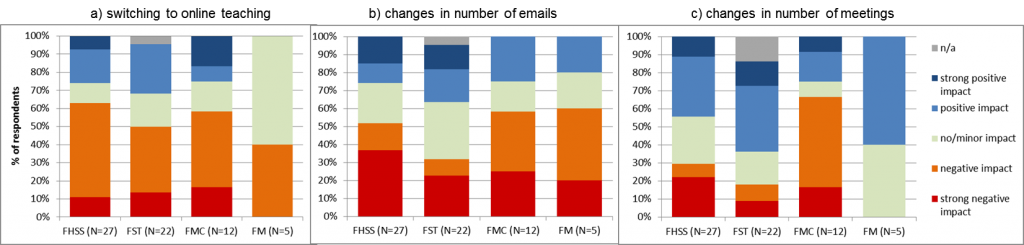

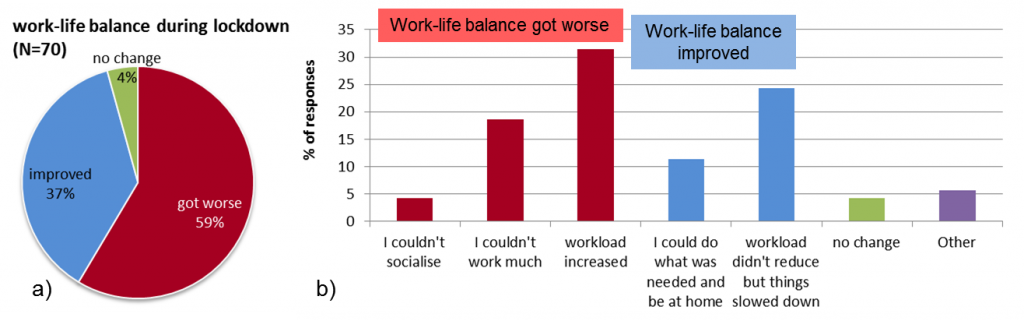

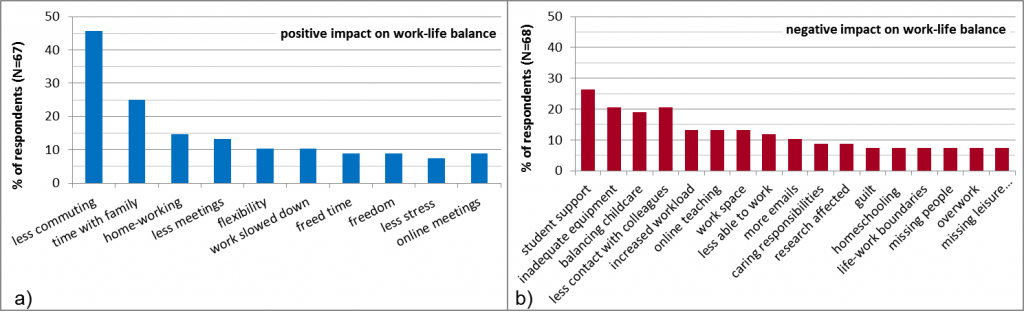

Figure 1. Changes in work-life balance of respondents during Covid-19 lockdown (a) and the selected reasons for identifying positive or negative change (b). ‘Other’ refers to other reasons for improved or worsened work-life balance.

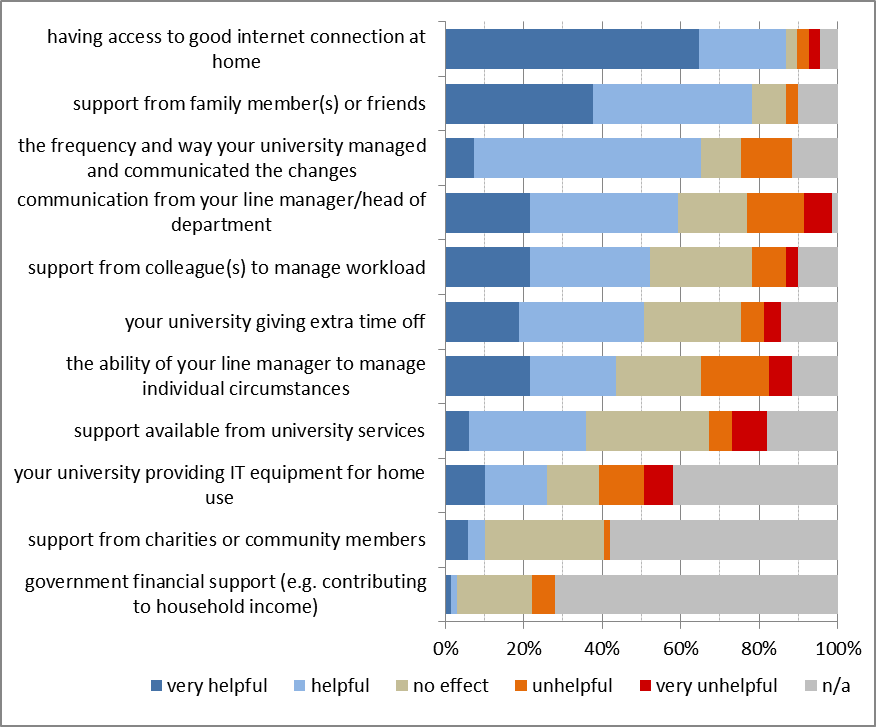

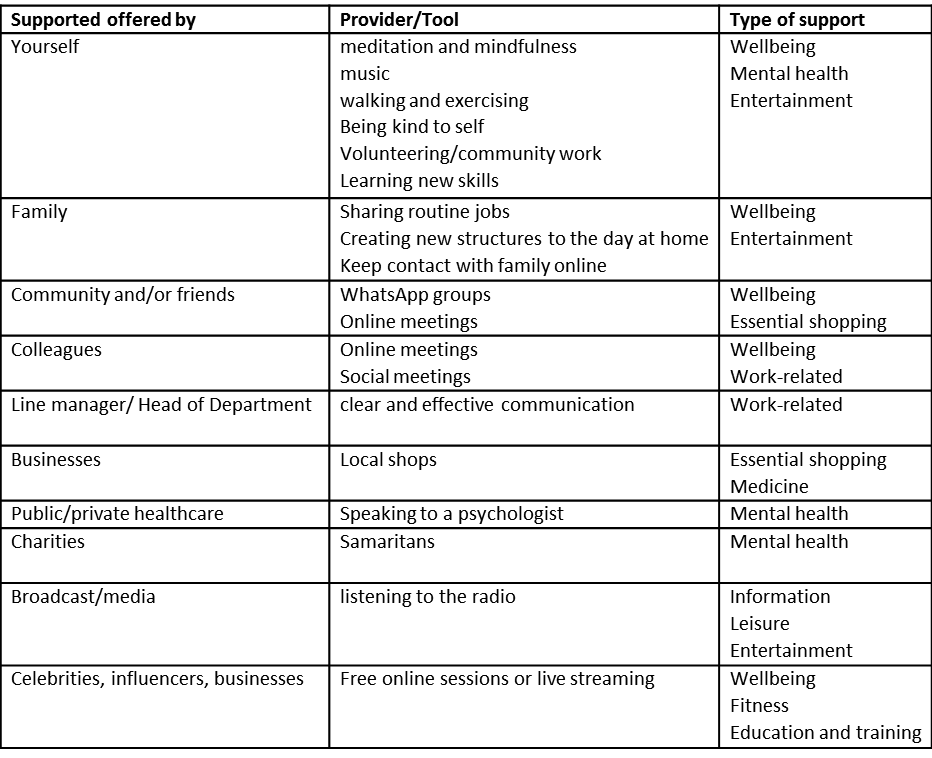

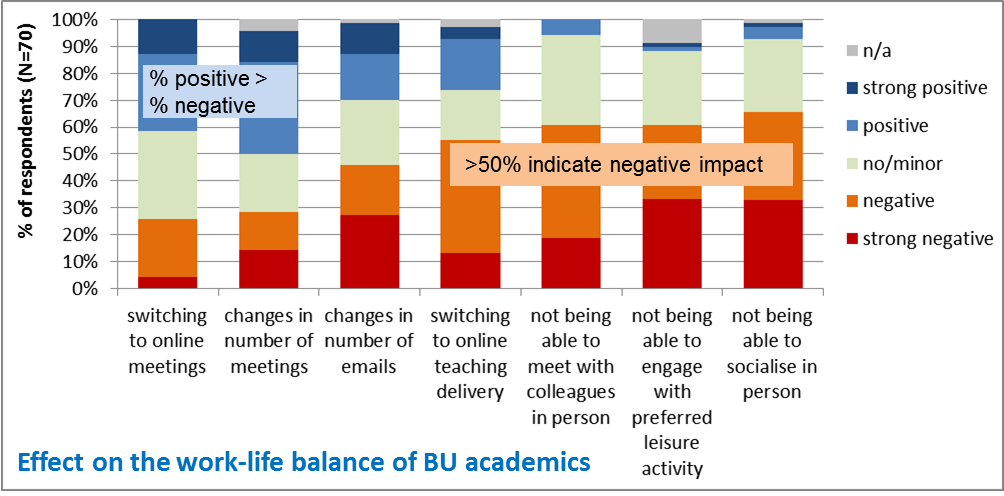

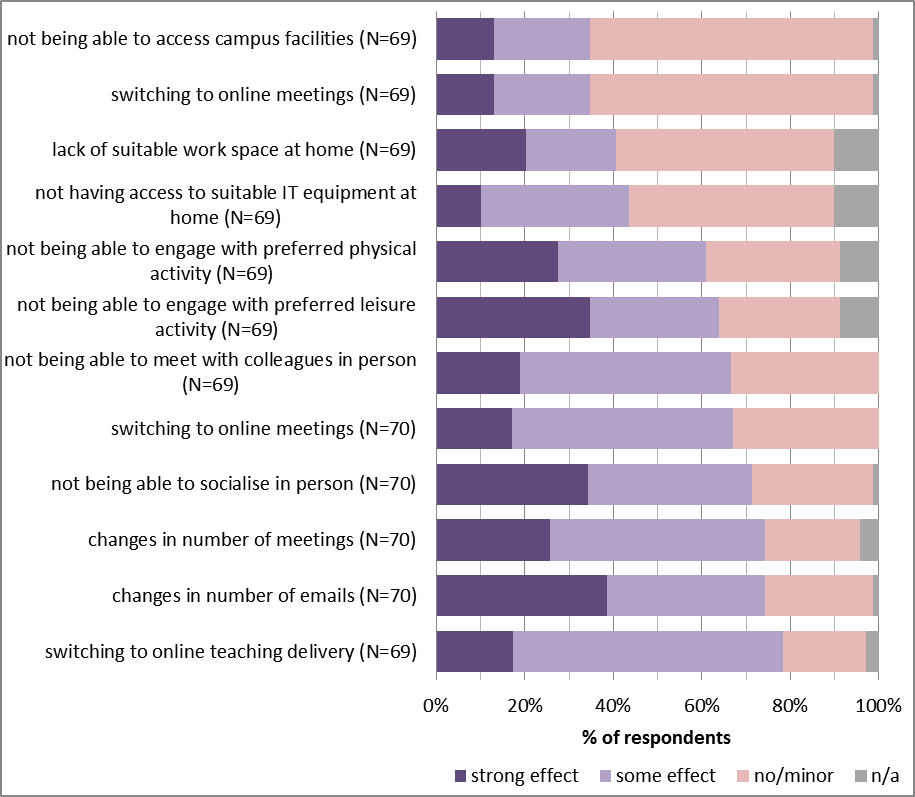

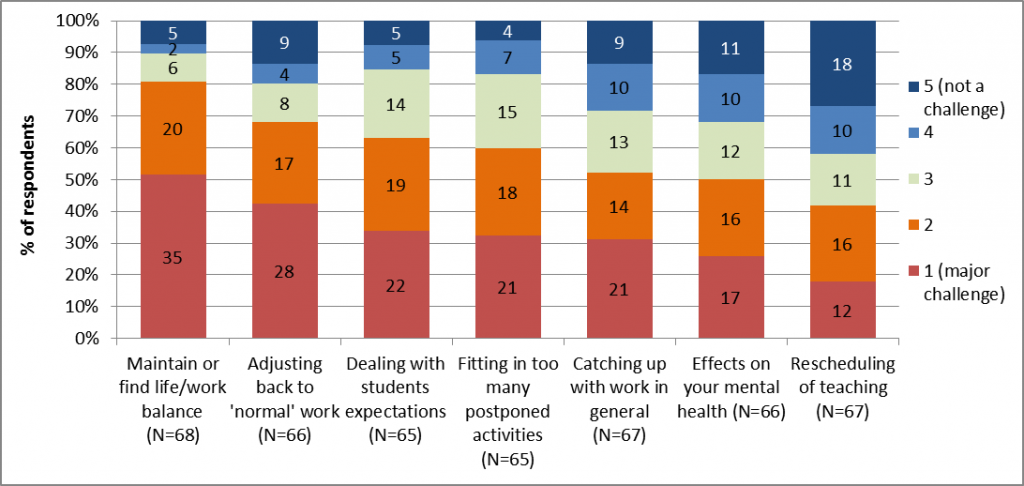

Figure 1. Changes in work-life balance of respondents during Covid-19 lockdown (a) and the selected reasons for identifying positive or negative change (b). ‘Other’ refers to other reasons for improved or worsened work-life balance. Figure 2. The level of impact of selected factors on the work-life balance of respondents during lockdown.

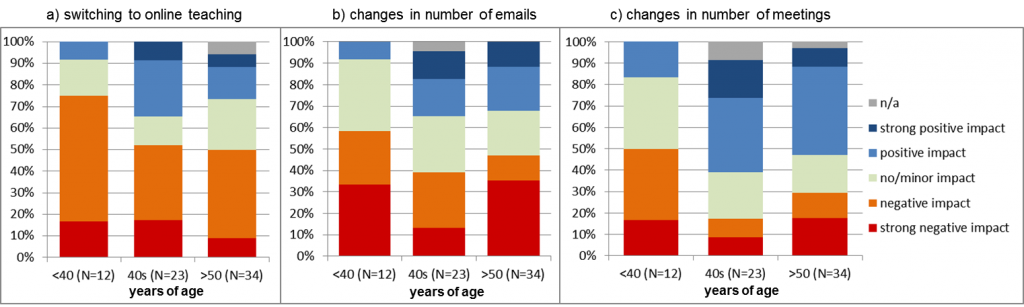

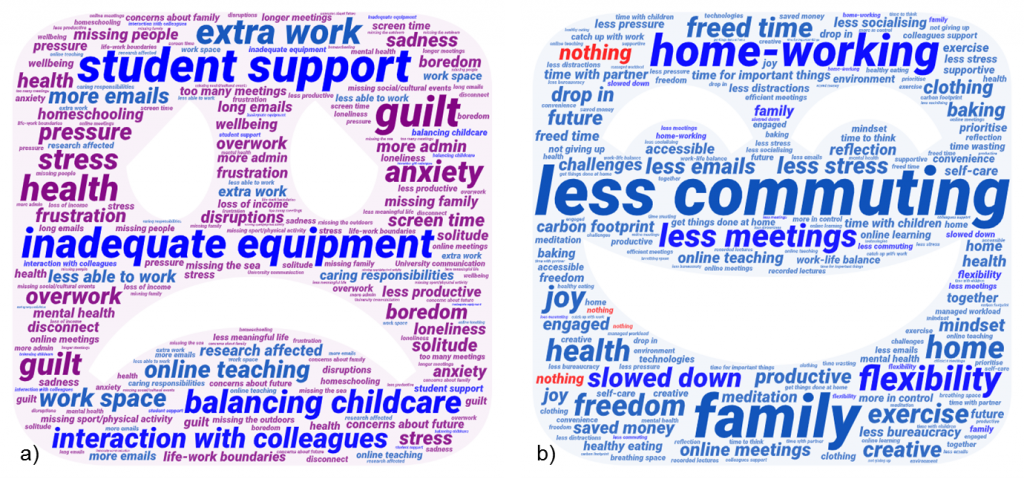

Figure 2. The level of impact of selected factors on the work-life balance of respondents during lockdown. Figure 3. Most cited top two aspects that have affected respondents’ work-life balance (a) positively and (b) negatively (showing categorised responses cited at least five times).

Figure 3. Most cited top two aspects that have affected respondents’ work-life balance (a) positively and (b) negatively (showing categorised responses cited at least five times). Figure 6. Major challenges identified regarding work at the end of lockdown.

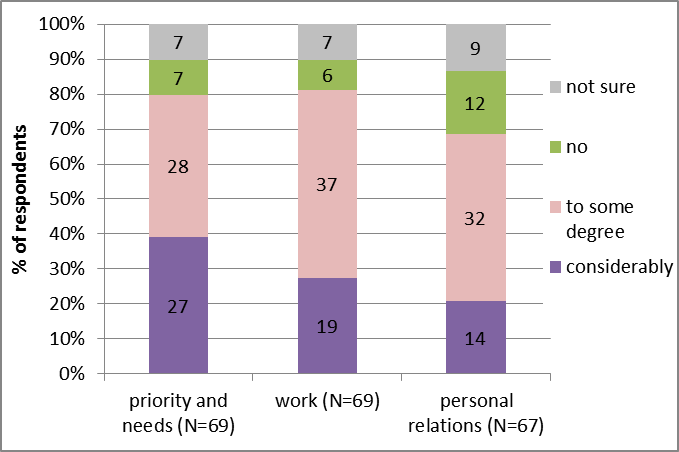

Figure 6. Major challenges identified regarding work at the end of lockdown. Figure 7. Perception of long-lasting changes brought by the C-19 outbreak.

Figure 7. Perception of long-lasting changes brought by the C-19 outbreak.

oject is in 4 phases: Explore, Design and Develop, Test and Evaluate. October 2018 will see the SAIL project move into the third phase: Test. The visit to Hunstanton provided an opportunity to see at first hand the challenges which face the area in terms of supporting an aging population now and in the future. The Mayor of Hunstanton hosted an evening reception in the Town Hall to welcome the SAIL Research Team and to learn more about the progress which is being made.

oject is in 4 phases: Explore, Design and Develop, Test and Evaluate. October 2018 will see the SAIL project move into the third phase: Test. The visit to Hunstanton provided an opportunity to see at first hand the challenges which face the area in terms of supporting an aging population now and in the future. The Mayor of Hunstanton hosted an evening reception in the Town Hall to welcome the SAIL Research Team and to learn more about the progress which is being made.

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives

SPROUT: From Sustainable Research to Sustainable Research Lives BRIAN upgrade and new look

BRIAN upgrade and new look Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh

Seeing the fruits of your labour in Bangladesh Exploring Embodied Research: Body Map Storytelling Workshop & Research Seminar

Exploring Embodied Research: Body Map Storytelling Workshop & Research Seminar Marking a Milestone: The Swash Channel Wreck Book Launch

Marking a Milestone: The Swash Channel Wreck Book Launch ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December

ECR Funding Open Call: Research Culture & Community Grant – Application Deadline Friday 12 December MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease