Research at Bournemouth University is looking at the effectiveness of comic artistry and storytelling in the sharing of public health messaging.

Research at Bournemouth University is looking at the effectiveness of comic artistry and storytelling in the sharing of public health messaging.

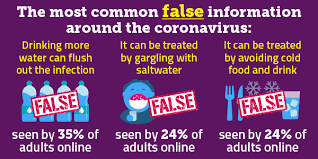

Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) the project will catalogue and analyse comic-style public health graphics, specifically those created during the Covid-19 pandemic, and seek to make recommendations on how the comic medium can be effective at delivering public health messaging to help drive behaviour change.

The idea for the research began as Dr Anna Feigenbaum, the lead researcher, and her colleagues Alexandra Alberda and William Proctor shared clever comic-style graphics with one another that had been created and shared on social media about Covid-19. These single, sharable, comic-style graphics blend the artistry and storytelling of comics with the Covid-19 messaging we have seen throughout the pandemic.

Dr Feigenbaum, an Associate Professor within the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University, said, “What we saw from these comic graphics was the way that the artistry and storytelling combined to share messages in a more emotive and interesting way. This built on work we were already doing on how public health messaging could utilise this medium to make their own messaging more engaging and even lead to better behavioural outcomes.”

José Blàzquez, the project’s postdoctoral researcher, has started work in collating over 1200 examples of comic-style Covid-19 messaging with the aim of understanding what makes them so compelling, and how this genre of communication could be further used to create what the project’s research illustrator, Alexandra Alberda, calls an “accessible, approachable and relatable” style of messaging when communicating important public health messages. The team aims to build a database that archives these comics, including information about their artistic and storytelling techniques, audience engagement, circulation, and what implications they may have for the sharing of health messaging in the future.

The final outcomes will be shared as a report and an illustrated set of good practice guidelines. Results will also be shared in the team’s edited collection Comics in the Time of COVID-19 and a special journal issue for Comics Grid. It is hoped these guidelines will inform public health communicators, as well as graphic designers and educators.

The team has even created their own Covid-19 web-comics, published by Nightingale on Medium. https://medium.com/nightingale/covid-19-data-literacy-is-for-everyone-46120b58cec9

Dr Feigenbaum continued, “Data comics are on a real upsurge as people look to make sense of the world through data visualisation, and there are some wonderful examples from amateur artists who have been incredibly clever and creative in taking what are, essentially, public health messages, and turning them into emotive comic-style stories.

“These sharable comic graphics are engaging and informed – there is a lot to learn here about the way we make sense of the world and how this genre could help us to see the communication of important messages in a whole new light. What we’re researching now could be seen as best practice in years to come.”

In addition to the main team of Dr. Feigenbaum, Dr. Blàzquez and Alexandra Alberda, this research will be conducted with Co-investigators Dr. Billy Proctor, Dr. Sam Goodman and Professor Julian McDougall, along with advisory partners Public Health Dorset, the Graphic Medicine Collective, Information Literacy Group and Comics Grid.

More information about the project will soon be available at www.covidcomics.org.

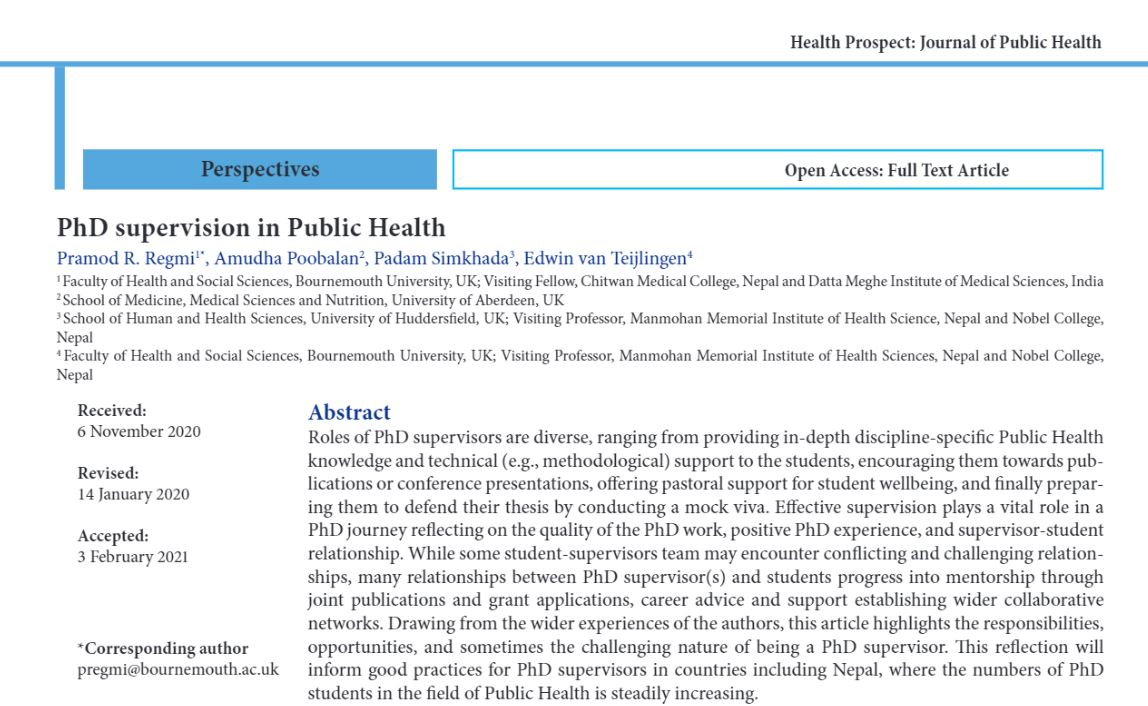

Recently, Health Prospect: Journal of Public Health published our article on ‘PhD supervision in Public Health’ [1]. The lead author is Dr. Pramod Regmi, with co-authors Prof. Padam Simkhada (FHSS Visiting Faculty) from the University of Huddersfield and Dr. Amudha Poobalan from the University of Aberdeen. The paper has a strong Aberdeen connection, the fifth oldest university in the UK. Three of us (Poobalan, van Teijlingen & Simkhada) use to work in the Department of Public Health at the University of Aberdeen (one still does), and three of us (Poobalan, Regmi & van Teijlingen) have a PhD from Aberdeen.

Recently, Health Prospect: Journal of Public Health published our article on ‘PhD supervision in Public Health’ [1]. The lead author is Dr. Pramod Regmi, with co-authors Prof. Padam Simkhada (FHSS Visiting Faculty) from the University of Huddersfield and Dr. Amudha Poobalan from the University of Aberdeen. The paper has a strong Aberdeen connection, the fifth oldest university in the UK. Three of us (Poobalan, van Teijlingen & Simkhada) use to work in the Department of Public Health at the University of Aberdeen (one still does), and three of us (Poobalan, Regmi & van Teijlingen) have a PhD from Aberdeen.

Research at Bournemouth University is looking at the effectiveness of comic artistry and storytelling in the sharing of public health messaging.

Research at Bournemouth University is looking at the effectiveness of comic artistry and storytelling in the sharing of public health messaging.

Dr. Ashraf cited on ‘Modest Fashion’ in The Guardian

Dr. Ashraf cited on ‘Modest Fashion’ in The Guardian NIHR-funded research launches website

NIHR-funded research launches website Academics write for newspaper in Nepal

Academics write for newspaper in Nepal New paper published on disability in women & girls

New paper published on disability in women & girls Global Consortium for Public Health Research 2025

Global Consortium for Public Health Research 2025 MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2025 Call ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar

ERC Advanced Grant 2025 Webinar Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published

Horizon Europe Work Programme 2025 Published Horizon Europe 2025 Work Programme pre-Published

Horizon Europe 2025 Work Programme pre-Published Update on UKRO services

Update on UKRO services European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease

European research project exploring use of ‘virtual twins’ to better manage metabolic associated fatty liver disease