Free training sessions for BU staff on engaging the public in your research, as part of the RKEDF.

Evaluation: developing your approach

Wednesday 21 April 2021

10.30am – 1.00pm

Online (Blackboard Collaborate)

This course will cover why evaluation is important, look at ways to get started, explore different techniques, and consider what your findings can tell you and your organisation or funder. We will also cover the ways in which evaluation can be used to generate evidence for impact. With an emphasis on how to conduct evaluation, join us for a programme of practical activities and discussion as together we demystify evaluation and find the fun in revealing and identifying your effectiveness. This workshop will be delivered by expert trainers from the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE).

▸ Aims of this workshop

- develop an awareness of the value and importance of evaluating public engagement.

- gain familiarity with the process of evaluation and the usefulness of planning.

- consider the uses of evaluation including improving activities; sharing good practice and reporting.

- begin to explore the issues and challenges of evaluating public engagement.

- continue to develop personal and professional skills, for example in communication, planning and critical reflection.

- increase confidence in evaluating public engagement activities.

- understand how evaluation ties in to impact

▸ How to book your place

- Complete this Approval Request email template and send it to your Head or Deputy Head of Department.

- Your HoD/DHoD can approve your registration session by forwarding the email to Organisational Development.

- You will be sent an Outlook Calendar meeting request to confirm your booking. This should be sent to you within 2 working days of receipt.

High quality public engagement

Monday 26 April 2021

2.00 – 4.30pm

Online (Blackboard Collaborate)

This course will develop your public engagement skills to a high level. It is aimed at academics with some public engagement experience, and/or those who have completed the ‘Getting started in Public Engagement’ session. The course offers an opportunity to reflect on past public engagement work and plans for the future. In particular, we will focus on developing your own plans with guided feedback and discussion. This workshop will be delivered by expert trainers from the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE).

▸ Aims of this workshop

- Explore frameworks and concepts that deepen thinking about People, Purpose and Process

- Apply those explorations to your own work

- Consider how to take the concepts into your own work in the future

▸ How to book your place

- Complete this Approval Request email template and send it to your Head or Deputy Head of Department.

- Your HoD/DHoD can approve your registration session by forwarding the email to Organisational Development.

- You will be sent an Outlook Calendar meeting request to confirm your booking. This should be sent to you within 2 working days of receipt.

Getting started in public engagement with research

Online recorded session now available

▸ Aims of this workshop

- This session aims to get academics from zero or little experience in public engagement with research (PER) to a position where they are confident carrying out PER activity with awareness of audience, delivery and evaluation.

▸ How to watch

- Watch the recorded session on Brightspace, delivered by Adam Morris, Engagement Officer at BU.

Tuesday 13th April – Thursday 15th April 2021

Tuesday 13th April – Thursday 15th April 2021

Upcoming opportunities for PGRs – collaborate externally

Upcoming opportunities for PGRs – collaborate externally BU involved in new MRF dissemination grant

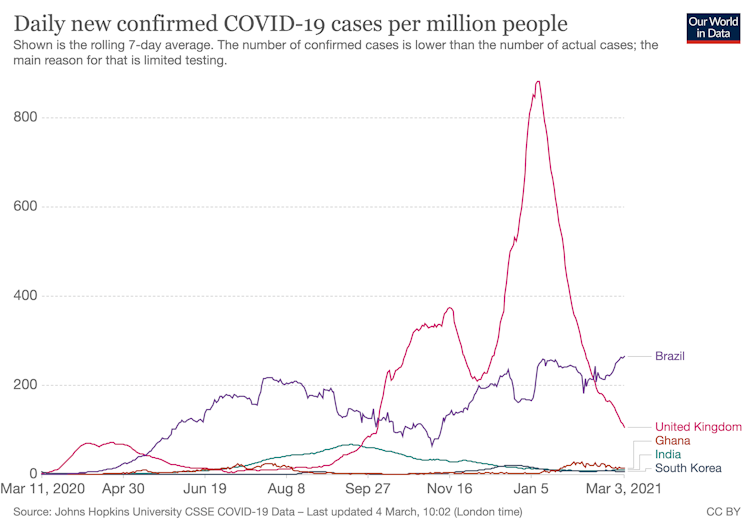

BU involved in new MRF dissemination grant New COVID-19 publication

New COVID-19 publication MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2024

MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowships 2024 Horizon Europe News – December 2023

Horizon Europe News – December 2023