EPA/Jasmin Brutus

By Dr Melanie Klinkner, Bournemouth University and Giulia Levi, Bournemouth University.

One of the darkest hours in recent human history, the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, has plenty of unpleasant parallels in today’s world, from Syria to Myanmar. 23 years after the massacre in and around the Bosnian enclave of Srebrenica, remembrance of what has been described as “scenes from hell, written on the darkest pages of human history” is as important as ever.

The events in and around Srebrenica between July 10-19 1995 are well known. In those few days, an estimated 8,000 Muslim Bosniaks were murdered by Bosnian Serb forces. Efforts to find, recover, identify and repatriate the victims’ remains are ongoing – and the task is a hugely complex one.

Every year at the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial Centre and Cemetery, more victims are laid to rest. This year, 35 people have been identified and will be buried. Of the 430 Srebrenica-related sites where human remains have been recovered, 94 are graves and 336 are surface sites with human remains scattered on the ground. Pathologists and anthropologists examined more than 17,000 sets of human remains related to Srebrenica, resulting in around 7,000 identifications, most of them via DNA. To gather enough DNA to make those identifications, more than 20,000 DNA samples had to be collected.

Slow justice

It was only in autumn 2017 that Ratko Mladić, a former general of the Bosnian Serb forces, was convicted of the crimes that took place in Srebrenica – genocide and persecution, extermination, murder, and the inhumane act of forcible transfer. Mladić is one of relatively few defendants to have appeared before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) charged with genocide.

This is because for a conviction on the grounds of genocide, the prosecution has to prove a catalogue of things. To be convicted of the crime of genocide, the accused must have deliberately intended “to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group as such”. Punishable under Article 4(3) of the ICTY Statute are also conspiracy to commit genocide, incitement to commit genocide, attempts to commit genocide and complicity in genocide. Two things have to be proven: the actus reus (the actual killings, serious bodily or mental harm and deliberate infliction of conditions designed to bring about the destruction of the group) and the mens rea (the specific intent to destroy the group).

Mladić’s 2017 conviction did not bring an end to all aspects of his case. In March 2018, both the defence and prosecution filed their notices of appeal. Though not in relation to Srebrenica, the prosecution submits that the trial chamber erred in two of its findings: first, that Bosnian Muslims in the areas of Foča, Kotor Varoš, Prijedor, Sanski Most and Vlasenica did not constitute a substantial part of the Bosnian Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and second, that Mladić (and others) did not intend to destroy those Bosnian Muslims. As a result, the proceedings are ongoing.

Bosnian Muslims carry coffins with remains of Srebrenica victims, 2017. EPA/Jasmin Brutus

During the 530 days of Mladić’s original trial, 377 witnesses appeared in court, some of them victims of war crimes. Victims often have many needs: to tell their stories, to contribute to public knowledge and accountability, to publicly denounce the wrongs that were committed against them and others, to bear witness on behalf of those who did not survive, and to receive reparations, public acknowledgement or apologies. They may wish to confront the accused, to find out the truth about what happened to their loved ones, to contribute to peace goals or to help prevent the perpetration of further abuse. Many risk their own personal safety to tell their stories, or those of victims who did not survive.

And yet, a recent report by international NGO Impunity Watch paints a bleak picture stating that “Western Balkan states have done very poorly when it comes to victim participation in [transitional justice] processes. Victims’ voices are marginalised and their rightful claims have been politicised by the different sides.”

Remembrance and responsibility

Impunity Watch describes a continuing “battleground of conflicting narratives, in which each side claims victimhood and blames the other for past abuses”. This does not bode well for the future.

The divisions in Bosnia are hard to ignore; Srebrenica’s Serb mayor, Mladen Grujičić, denies that the genocide occurred, as does Milorad Dodik the leader of Bosnia’s Serb-led entity Republika Srpska. Many Serbian nationalists regard Mladić as a war hero. To many people, his conviction would therefore be effectively meaningless.

And yet, plenty of civil society activities, interventions and educational programmes have been devised. In Bosnia, Youth United in Peace and Youth Initiative for Human Rights, to name but two, offer young people the chance to hear different perspectives about the past through workshops and visits to commemorative places of all sides. Such projects try to counter ethnic segregation to offer shared space for dialogue.

In a speech to the United Nations in 1958, Eleanor Roosevelt famously said:

Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighbourhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works.

Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.

All too often this is forgotten. But with stark societal divisions palpable in many parts of the world, we have to keep reminding ourselves that all others are above all else human beings. Only if we do that will the idea of human rights be meaningful.

Dr Melanie Klinkner, Principal Academic in International Law, Bournemouth University and Giulia Levi, PhD Candidate, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Bournemouth University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Professor Maria-Victora Sanchez-Vives is the leader of an associated project within the large Human Brain Project initiative,

Professor Maria-Victora Sanchez-Vives is the leader of an associated project within the large Human Brain Project initiative,

Digital Tethering: Understanding Digital Immersion within Streaming and E-Sports

Digital Tethering: Understanding Digital Immersion within Streaming and E-Sports

Welcome to BU from China! From the beginning to the end of your studies at BU, let’s focus on the middle bit and the all-important ‘sandwich placement’!

Welcome to BU from China! From the beginning to the end of your studies at BU, let’s focus on the middle bit and the all-important ‘sandwich placement’!

FHSS academics teaching in Nepal

FHSS academics teaching in Nepal New weight change BU paper

New weight change BU paper One week to go! | The 16th Annual Postgraduate Research Conference

One week to go! | The 16th Annual Postgraduate Research Conference Geography and Environmental Studies academics – would you like to get more involved in preparing our next REF submission?

Geography and Environmental Studies academics – would you like to get more involved in preparing our next REF submission? Congratulations to three former BU staff

Congratulations to three former BU staff MSCA Staff Exchanges 2024 Call – internal deadline

MSCA Staff Exchanges 2024 Call – internal deadline Applications are now open for 2025 ESRC Postdoctoral Fellowships!

Applications are now open for 2025 ESRC Postdoctoral Fellowships! Horizon Europe – ERC CoG and MSCA SE webinars

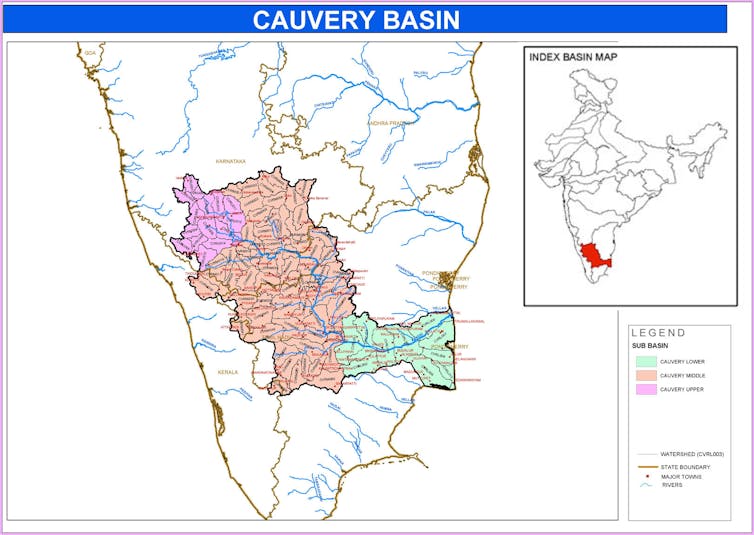

Horizon Europe – ERC CoG and MSCA SE webinars MaGMap: Mass Grave Mapping

MaGMap: Mass Grave Mapping ERC grants – series of webinars

ERC grants – series of webinars